|

子どもの健康と環境センター

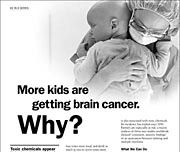

Center for Children's Health and the Environment (CCHE) ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙掲載広告の科学的裏づけ文書 意見広告 2 多くの子どもたちが脳腫瘍にかかっている Scientific Background Paper for the "More kids are getting Brain Cancer" NY TIMES ad 2 http://www.childenvironment.org/pdfs/NYT%20Ads/6-00077%20FINAL_Brain_Cancer_Ad_NYT.pdf 訳:安間 武 (化学物質問題市民研究会) 掲載日:2003年9月28日 このページへのリンク http://www.ne.jp/asahi/kagaku/pico/kodomo/cche/nyt_ad_2.html

多くの子どもたちが脳腫瘍にかかっている 残留性有機汚染物質が増えている がんの危険性 : 非ホジキンス・リンパ腫、多発性骨髄腫、そして小児がん がんについてのよいニュースは、全体として死亡率が減少していることである。これは、早期発見、治療の進歩、そして予防のための努力 (喫煙の減少、副流煙への曝露の減少、ある種の産業化学物質とアスベストへの曝露の減少) のおかげである。ある種のがんの発病率もまた減少している (男性の肺がん、子宮ガン、胃がん) しかし、このよいニュースの陰に、深刻な悪いニュースがある。報告されているいくつかのがんの発病率−人口1000人当りの新たな発病者−は増加し続けている。発病率が増加しているいくつかのがんは残留性有機汚染物質 (POPs) と農薬に関連していると考えられる。最もはっきりと POPs 及び農薬に関係しているがんは、非ホジキンス・リンパ腫、多発性骨髄腫、そして小児がんである。これらのがんの増加は、がん早期発見技術の改善や医療機関で健診を受ける人が増えたことも若干は影響しているかもしれないが、それが増加の原因ではない。 POPs とがんの関連性は極めて強い。 POPs と最も関連性が強いがんは非ホジキンス・リンパ腫 (NHL) である。その発病率は1950年以来、3倍となっている[1]。 AIDS もこの増加には幾分寄与しているが、しかし増加の傾向は AIDS が最初に発見される以前から見られている[2]。 NHL は多くの POPs、とりわけ、フェノール系除草剤と関連性があり、それらは有毒な POPs であるダイオキシンを含んでいる[3]。最もよく知られている除草剤は、エージェント・オレンジで、これは2つの成分 (2,4,5,-T と 2,4-D) の混合物 であり、これもまたダイオキシンを含んでいる。エージェント・オレンジはベトナム戦争の時に東南アジアで広範囲に散布された。多くのベトナム従軍兵士が曝露した。ベトナム退役軍人と工場でエージェント・オレンジの製造に従事した作業者[4] のグループは、NHL の発病率が高く、そのリスクはエージェント・オレンジへの曝露の程度に比例する[5]。 アメリカでは 2,4,5-T は1979年に禁止されたが[6]、 2,4-D とその他のフェノール系除草剤は広くアメリカの農業、芝生、園芸、学校、公園で使用されている。一般のアメリカ人に比べて農家の人や農業作業者は曝露量が多い。彼らは通常 NHL の発病率が高い。ベトナム退役軍人と同様に、フェノール系除草剤への曝露が多ければ NHL へのリスクも高くなる[7]。 同様な関連性は他の国々でも見られる。オランダの一般国民に比べて、職業上、フェノール系除草剤に曝露するオランダ人男性の NHL リスクは通常のリスクよりも2倍高い[8]。カナダでは職業上、殺虫剤や除草剤に曝露する男性は NHL リスクが高く、曝露期間の増大が直接リスクに関連している[9]。スウェーデンの材木伐採従事者で高濃度のフェノール系除草剤に曝露した人たちもまた高い NHL リスクを示している[10]。 困惑することには、NHL のリスク増加を招くのはフェノール系除草剤への職業上の曝露だけではないということである。スウェーデンの研究によれば、一般国民もフェノール系除草剤への曝露が増えて NHL リスクが増大している[11]。イタリア北部の農村地帯で研究者が調べたところ、2,4-D へのの曝露が低い地域の人々に比べ、2,4-D への曝露が高い人々は2倍の NHL リスクがあった[12]。 フィンランドの調査で思いがけず NHL 発病率の高い地域があった。その理由は、その地域の製材所が地域の水源を化学的にフェノール系除草剤に非常に関連したクロロフェノールで汚染していたためであることがその調査でわかった[13]。同様な事象はアイオワ州でも見られ、NHL の発病率は郡毎に大きく変動するが、最も発病率の高い複数の郡では、飲料水源がフェノール系除草剤に化学的に似ている有機塩素系殺虫剤ディルドリンで汚染されていた[14]。 たとえ飲み水は汚染されていなくても、家庭で、芝生で、園芸でフェノール系除草剤は広く使われているので、NHL のリスクはやはりある。これらの製品はしばしば 2,4-D やその他の NHL リスクに関連する成分を含んでいる。南カリフォルニア大学の調査によれば、親が家庭で除草剤を使用する子どもは、使用しない親の子どもに比べて7倍も NHL のリスクが高いとしている[15]。またドイツの調査では、定期的に害虫駆除業者に消毒させている家庭の子どものNHL リスクは平均リスクの2.6倍高いとしている[16]。 また、血液がんとリンパ腫のリスクは、他の化学物質、DDT、PCBs、ベンゼン、有機塩素系殺虫剤などへの曝露で増大する[17]。国立がん研究所の研究者は74人の NHL 患者と147人の健康なコントロール群から血液サンプルを採取した。残留性有機汚染物質 (POPs) の血中濃度が最も低い人々に比べて、最も高い人々の NHL リスクは4.5倍であった[18]。NHL はまた暗色系染髪剤に使われる化学物質とも関連していた[19]。 分子レベルでは NHL は染色体14と18の突然変異性に強く関連している。ミネソタにおける殺虫剤散布者の調査によれば、POPs への曝露によりこれらの突然変異が見られる[20]。 POPs が原因で発病率が増加する他のがんとして多発性骨髄腫 (multiple myeloma (MM) ) がある。その発病率は1950年以来3倍となっている[21]。MM は様々な産業用及び農業用化学物質、特に、塗料、石油、溶剤、殺虫剤[22]、そして暗色系染髪剤などへの曝露と関連している[23]。工業国の人の方が非工業国の人よりもこの病気の発病率が高い[24]。 POP 殺虫剤に職業的に曝露する農民はリスクが最も高い[25]。実際、世界中の32の研究調査が、”農業と MM との関連性について、一貫した明らかな傾向”を示している[26]。 MM はまたダイオキシンへの曝露にも関係している。1976年、イタリアのセベソでの殺虫剤製造工場での爆発事故で放出された化学物質には大量のダイオキシンが含まれていた。1990年代の初頭までに、周辺地域の住民は、MM を含むいくつかのがんの発病率が高くなった[27]。 がんはまた子どもたちをも脅かす。実際、がんは、けがや暴力に次ぐ子どもの死亡原因である[280]。国立がん研究所によれば、子どものがんは1973年以来、13%増加している[29]。しかし、同時期の小児がんの発病率はもっと急速に増加している。小児 NHL は30%の増加、小児脳腫瘍は21%の増加、そして子どもの急性リンパ腫は21%の増加である[30]。POPs がこれらの増加に関係しているのではないか? そのことは定かではないが次のことを考えてみよう。 子どもは喫煙をしない、アルコールを飲まない、POPs への職業上の曝露はない。しかし大人に比べると、子どもは水、食物、空気を通じてより多くの汚染物質に曝露する。体重当り、子どもは大人の2倍の空気を吸い、3〜4倍の食物を食べ、年令にもよるが、2〜7倍の水を飲む[31]。多くの研究調査が、子どもはシラミとり用シャンプーを含む家庭用、芝生用、園芸用殺虫剤への曝露が増大しており、従って、NHL、脳腫瘍[32]、白血病[33]、その他のがん[34]のリスクが増大している。親の POPs への曝露の増加もまた子どもの NHL[35]、脳腫瘍[36]、白血病[37]、その他のがん[38]を増加させている。他の調査は乳幼児が母乳を通じて POPs に曝露しているとしている[39]。 恐らく、POPs への曝露だけが NHL、MM、小児 NHL、小児脳腫瘍、小児白血病の増加原因ではない。実際、POPs への曝露とこれらのがんとの間には関連性がないとする調査研究もわずかではあるが存在する[40]。しかし、我々は、POPs −塩素系殺虫剤や産業化学物質−がこれらの病気の増大に明らかに寄与していることを示す確かな証拠があると確信している。 「後悔するより安全を」 (Better safe than sorry)。我々は不確実性は残っているものの、発達神経有毒物質を可能な限り速やかに、理想的には今すぐ、廃止するよう果敢に行動を起すことの正当性を示す十分な証拠があると信じている。 科学的裏づけ文書 [1] Altman, L.K. "Lymphomas Are On the Rise, and No One Knows Why," NY Times, May 24, 1994. [2] Hardell, L. and M. Eriksson. "A Case-Control Study of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphma and Exposure to Pesticides," Cancer (1999) 85:1353-1360. P. Hartge et al. "Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas," In R. Doll et al. (eds.) Trends in Cancer Incidence and Mortality. Cancer Surveys 19/20 (Cold Spring Harbor Larboratory Press, Plainview, NY, 1994) pp. 423-453. [3] Zahm, S.A. and A. Blair, "Pesticides and Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma," Cancer Research (1992 suppl.) 52:5485s-5488s [4] Fingerhut, M. New England Journal of Medicine. [5] Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Veterans and Agent Orange: Health Effects of Pesticides Used in Vietnam. (National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.1994) [6] Colburn, T. et al. Our Stolen Future (Plume, NY, 1997) p. 114. [7] Keller-Byrne, J.E. et al. "A Meta-analysis of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Among Farmers in the Central U.S." Am. J. Industiral Medicine (1997) 31:442-444. Zahm, S.H. et al. "A Case-Control Study of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma and the Herbicide 2,4-D in Eastern Nebraska," Epidemiology (1990) 1:349-356. Zahm, S.H. and A. Blair. "Cancer Among Migrant and Seasonal Farmers: An Epidemiological Review," Am. J. Industrial Med. (1993) 24:753-766. Blair, A. et al. "Clues to Cancer Etiology from Studies of Farmers," Scandinavian J. of Work Environment and Health (1992) 18:209-215. Davis, D.L. "Agricultural Exposures and Cancer Trends in Developed Countries," Environ. Health Perspectives (1992) 100:39-44. [8] Hooiveld, M. et al. "Second Follow-Up of a Dutch Cohort Occupationally Exposed to Phenoxy Herbicides, Chlorophenols, and Contaminants," Am. J. Epidemiology (1998) 147:891-901. [9] Mao, Y. et al. "Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma and Occupational Exposure to Chemicals in Canada," Annals of Oncology (2000) suppl. 1:69-73. [10] Thorn, A. et al. "Mortality and Cancer Incidence Among Swedish Lumberjacks Exposed to Pheenoxy Herbicides," Occupational Environmenal Medicine (2000) 57:718-20/ [11] Hardell, L. and M. Eriksson. "A Case-Control Study of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphma and Exposure to Pesticides," Cancer (1999) 85:1353-1360. [12] Fontana, A. et al. "Incidence Rates of Lymphomas and Environmental Measurements of Phenoyx Herbicides: Ecological Analysis and Case-Control," Archives of Environ. Health (1998) 53:384-387. [13] Lampi, P. et al. "Cancer Incidence Following Chlorophenol Exposure in a Community in Southern Finland," Archives of Environ. Health (1992) 47:167-175. [14] Cantor, K.P. et al. "Water Pollution," in D. Schottenfield and J.F. Fraumeni (eds.) Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention, 2nd ed. (Oxford U. Press, Oxford, Eng., 1996) pp. 418-437. [15] Buckley, J.D. et al. "Pesticide Exposures in Children with Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma," Cancer (2000) 89:2315-=2321. [16] Meinert, R. et al. "Leukemia and non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma in Childhood Exposure to Pesticides: Results of a Register-Based Case-Control Study in Germany," Am. J. Epidemiology (2000) 151:639. [17] Zahm, S.A. "The Role of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Development of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma in Women," Archives of Environ. Health (1993) 48:253-258. [18] Rothman, N. et al. "A Nested Case-Conrol Study of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma and Serum Organochlorine Residues," Lancet (1997) 350(9073):240-244. [19] Correa, A. et al. "Use of Hair Dyes, Hematopoietic Neoplasms, and Lymphomas: A Literature Review. II. Lymphomas and Multiple Myeloma," Cancer Investigations (2000) 18:467-479. Altekruse, S.F. et al. "Deaths from Hematopoietic and Other Cancers in Relation to Permanent Hair Dye Use in a Large Prospective Study," Cancer Causes and Control (1999) 10: 617-625. Thun, M.J. et al. "Hair Dye Use and Risk of Fatal Cancers in U.S. Women," Journal of the National Cancer Institute (1994) 86:210-215. [20] Garry, V.F. et al. "Pesticide Applicators with Mixed Pesticide Exposure: G-Banded Analysis and Possible Relationship to Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma," Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, and Prevention (1996) 5:11-16. Garry, V.F. "Survey of Health and Use Characterization of Pesticide Appliers in Minnesota," Archives of Environ. Health (1994) 49:337-343. [21] Steingraber, S. Living Downstream (Vintage, NY, 1998) p. 54. [22] Herrington, L.J. et al. "Multiple Myeloma," in D. Schottenfield and J.F. Fraumeni (eds.) Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention, 2nd ed. (Oxford U. Press, Oxford, Eng. 1996). Eriksson, M. and M. Karlson. "Occupational and Other Environmental Factors in Multiple Myeloma: A Population-Based Case-Conrol Study," British J. of Industrial Med. (1992) 49:95-103. [23] Correa, A. et al. "Use of Hair Dyes, Hematopoietic Neoplasms, and Lymphomas: A Literature Review. II. Lymphomas and Multiple Myeloma," Cancer Investigations (2000) 18:467-479. Altekruse, S.F. et al. "Deaths from Hematopoietic and Other Cancers in Relation to Permanent Hair Dye Use in a Large Prospective Study," Cancer Causes and Control (1999) 10: 617-625. Thun, M.J. et al. "Hair Dye Use and Risk of Fatal Cancers in U.S. Women," Journal of the National Cancer Institute (1994) 86:210-215. [24] Schwartz, J. "Multinational Trends in Multiple Myeloma," in D.L. Davis and D. Hoel (eds.) Trends in Cancer Mortality in Industrialized Countries, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. (1990) 609:215-224. [25] Zahm, S.H. et al. "Pesticides and Multiple Myeloma in Men and Women in Nebraska," in H.H. McDuffie et al. (eds.) Supplement to Agricultural Health and Safety: Workplace, Environment, Sustainability. (U. of Saskatchewan Press, Saskatoon, Canada, 1995), pp. 75-81. Zahm, S.H. and A. Blair. "Cancer Among Migrant and Seasonal Farmers: An Epidemiological Review," Am. J. Industrial Med. (1993) 24:753-766. [26] Khuder, S.A. and A.B. Mutgi. "Meta-Analysis of Multiple Myeloma and Farming," Am. J. Industrial Med. (1997) 32:510-516. [27] Bertazzi, P.A. et al. "Cancer Incidence in a Population Accidentally Exposed to Dioxin," Epidemiology (1993) 4:398-406. [28] National Center for Health Statistics, CDC, 2000. [29] NCI. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973-1997. [30] NCI. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973-1997. [31] Landrigan, P.J. et al. "Children's Health and Environment: A New Agenda for Prevention Research. Environmental Health Perspectives (1998) 106, suppl 3. Robison, L.L. et al. "Assessment of Environmental and Genetic Factors in the Etiology of Childhood Cancers: The Children's Cancer Group Epidemiology Program," Environ. Health Perspectives. (1995) 103, suppl. 6:111-116. Zahm. S.H. and S.S. Devesa, :"Childhood Cancer: Overview of Incidence Trends and Environmental Carcinogens," Environ. Health Perspectives. (1995) 103, suppl. 6:177-184. [32] Leiss. J.K. and D.A. Savitz, "Home Pesticide Use and childhood Cancer: A Case-Control Study," Am. J. Public Health (1995) 85:249-252. [33] Buckley, J.D. et al. "Pesticide Exposures in Children with Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma," Cancer (2000) 89:2315-2321. Meinert, R. et al. "Leukemia and non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma in Childhood Exposure to Pesticides: Results of a Register-Based Case-Control Study in Germany," Am. J. Epidemiology (2000) 151:639. [34] Infante, P.F. et al. "Blood Dyscrasias and Childhood Tumors and Exposure to Chlordane and Heptachlor," Scandinavian J. of Work Environment and Health (1978) 4:137-150. [35] Magnani, C. et al. OParental Occupation and Other Environmental Factors in the Etiology of Leukemias and Non-HodgkinOs Lymphomas in Childhood: A Case-Control Study,O Tumor (1990) 76:413-419. Olsen, J.H. et al. OParental Employment at Time of Conception and Risk of Cancer in Offspring,O European J. of Cancer (1991) 27:958-965. [36] O'Leary, L.M. et al. "Paraental Exposures and Risk of Childhood Cancer: A Review," Am. J. of Industrial Med. (1991) 20:17-35. [37] Magnani, C. et al. "Parental Occupation and Other Environmental Factors in the Etiology of Leukemias and Non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas in Childhood: A Case-Control Study," Tumor (1990) 76:413-419. Olsen, J.H. et al. "Parental Employment at Time of Conception and Risk of Cancer in Offspring," European J. of Cancer (1991) 27:958-965. Lowengart, R.A. et al. "Childhood Leukemia and Parents' Occupational and Home Exposures," J. Nat. Cancer Inst. (1987) 79:39-46. [38] Feingold, L. et al. "Use of a Job-Exposure Matrix to Evaluaate Parental Occupation and Childhood Cancer," Cancer Causes and Control (1992) 3:161-169. Olsen, J.H. et al. "Parental Employment at Time of Conception and Risk of Cancer in Offspring," European J. of Cancer (1991) 27:958-965. Van Steensel-Moll, H.A. et al. "Chilhood Leukemia and Parental Occupation: A Register-Based Case-Control Study," Am. J. of Epidmiology (1985) 121:216-224. Wilkins, J.R. et al. "Occupational Exposures Among FGathers of Children with Wilm's Tumor," J. Occupational Med. (1984) 26:427-435/\. [39] Laug, E.P. et al. "Occurrence of DDT in Human Fat and Milk." Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Occupational Medicine (1951) 3:245-2436. Rogan, W.J. et al. "Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) and Dichlorodiphenyl Dichloroethene (DDE) in Human Milk: Effects of Maternal Factors and Previous Lactation," Am. J. Public Health (1986) 76:172-177. Schecter, A. et al. "Dioxins in U.S. Food and Estimated Daily Intake," Chemosphere (1994) 29:2261-2265. Rogan, W.J. et al. "Pollutants in Breast Milk," New England J. Med. (1980) 302:1450-1453. Schreiber, J.S. "Predicted Infant Exposure to Tetrachloroethylene in Human Breast Milk," Risk Analysis (1993) 13:515-524. [40] Burns, C.J. et al. "Mortality in Chemical Workers Potentially Exposed to 2,4-D, 1945-1994: An Update," Occupational Environmental Medicine (2001) 58:24-30. Lynge, E. "Cancer Incidence in Danish Phenoxy Herbicide Workiers, 1947-1993," Environ. Health Perspectives (1998) 106 suppl. 2:683-688. Semenciw, R.M. et al. "Multiple Myeloma Mortality and Agricultural Preactices in Prairie Provinces of Canada," J. of Occupational Med. (1993) 35:557. Pearce, N.E. et al. "Case-Conrol Study of Multiple Myeloma and Farming," Brit. J. of Cancer (1986) 54:493-500. |