|

THE FRIDAY MOSQUE

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

|

THE FRIDAY MOSQUE

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

The Friday Mosque of Isfahan has a history of more than 1,000 years. It is said that its First Arabic-type construction had existed in the 8th century of the Abbasid dynasty and its size might have been that of the current mosquefs courtyard. It was reconstructed in the 9th century and was enlarged greatly in the 11th century of the Buwayhid dynasty (932-1062). In the ruling era of Seljuk Turks (1038-1157), it was thoroughly remodeled and beautified, becoming the largest mosque representing the Persian capital Isfahan. While it is on Sunday in Christianity to read Mass in a church, Islam holds a congregational worship on Friday (as it is not a Sabbath, one can work) in a mosque, which is called Friday mosque. Principally, it is a place for worship where all the cityfs male members can attend, making it usually the largest mosque in a city. In accordance with the rapid increase of Muslims, early mosques became full to accommodate all inhabitants of their cities and were obliged to enlarge their scales. The Mezquita in Cordoba is a typical example of repeating enlargement at short intervals.

In Arabic, Friday is eJumuaf and congregation is eJâmiuf, both of which are derived from eJamâf (meaning gather), so a mosque for congregational worship on Friday is called eMasjid al Jumuâf (Friday mosque) or eMasjid al Jâmiuf (congregational mosque).

In Persian it is called eMasjid-e Jâmif (congregational mosque) or eMasjid-e Jomê (Friday mosque). In this site, I basically use eMasjid-e Jamif.

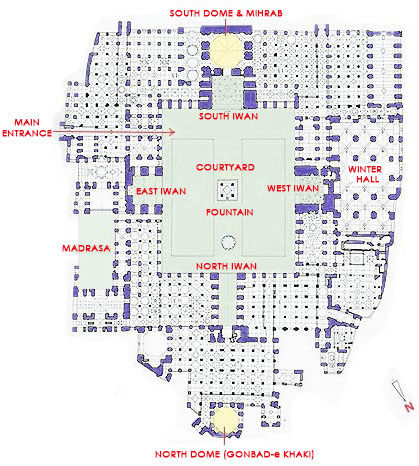

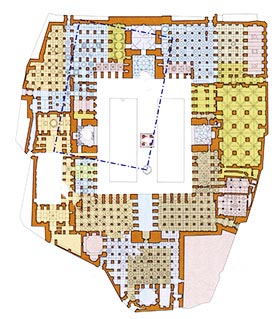

(From Henri Stierlin, Architecture de l'Islam, 1979, Office du Livfre) The schema given far below is clearly perceived here and the strangeness of the situation of its entrance passage too. Hypostyle halls of various types and ages were intricately added.  The upper left rectangle demarcated with a chain line shows the scale and place of the initial Friday Mosque in Isfahan. (55 x 65m) as the original mosque.@The colors indicate several dynasties that constructed hypostyle halls. (From Patrick Ringgenberg "Guide Culturel de l'Iran", 2006, Tehran) Just like parish churches everywhere in the Christian sphere, there are district mosques everywhere in the Islamic sphere. In the Catholic Church, there is a hierarchy of priests, according to which their churches are graded. First of all, the head church is Saint Peterfs Basilica in the Vatican presided by the Pope. Then each diocese has a cathedral presided by a Bishop, under which are parish churches with priests, and furthermore simple oratories (chapels) without priests. Such a pyramidal church system does not exist in Islam, or rather, there is no priesthood in Islam. Persons who lead a mass worship in a mosque are called eImamsf, but they are not professionals without much difference from the general faithful. Therefore, one mosque does not govern or control many other mosques, and any mosque is equal to any other. Since there is no parish system or jurisdiction system, a follower does not belong to a particular mosque, being able to freely worship in any convenient mosque.

Birdfs eye & long-distant views of the Friday Mosque The land of Iran was called ePersiaf in Europe, which was Latin denomination derived from Greek ePersisf, which itself was from the ancient ePârsaf region (current province of Fars and around). Although the Persian Empire of Achaemenids and Sassanids extended their power from Central Asia to Egypt, the Sassanids were destroyed by the army of Islam in the 7th century and their main religion was converted from Zoroastrianism to Islam. The first Islamic works in Iran were produced in the eras ruled by Umayyads in Damascus and Abbasids in Baghdad, among which a few are still extant such as the Friday mosques in Damghan and Nayin. It can be said that the intrinsic character of Iranian (Persian) architecture was formed as late as under the Seljuk dynasty (1038-1157) of Turks who came from Central Asia in gradual military campaigns.

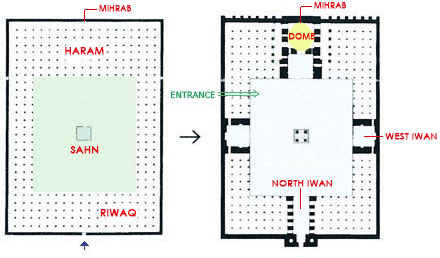

As I wrote on the page of gClassification of Mosquesh, the most classical mosque was eArabic typef, that is the simple hypostyle hall, on which Persians added new elements: domes and Iwans. While they built a dome above the center of the worship room, they also set Iwans at the center of each Riwaq and Haram (worship room) surrounding the Sahn (courtyard), with the result of establishing the eFour-Iwan type mosquef.

However, as seen in the schema shown below, notwithstanding having made a symbolic symmetric courtyard, the situation of the entrance passage seems to be very strange, looking to have been forcedly put in an unsuitable part of the Riwaq. Notwithstanding this appropriate stage, the North Dome (Gombad-e Khaki), facing with the South Dome in a distance, was constructed by the Wazir, Nizam al-Mulk, on that axis further north of the Northern Iwan. In those days the eastern and western Iwans were also erected forming a Four-Iwan type mosque favorably, but in the next era of Il-Khanate dynasty was constructed the North Hypostyle hall, which connects the Northern Iwan and Gonbad-e Khaki, resulting that the Northern Iwan lost the function of the entrance to the mosque. Thus, the mosque might have been compelled to assign a part of eastern Riwaq for the anomalous entrance.

Among buildings surrounding the courtyard, that of the Macca side is called eHaramf (worship room) and the other three eRiwaqsf. Early mosques, which began with the Prophetfs Mosque in Medina, had wooden roofs with horizontal beams on brick or stone walls to walls. It seems to be a better image for an actual Arabic type mosque to have cut a central square part including its columns and beams out of a large flat hypostyle hall to get a courtyard than to consider that independent corridors encircle a courtyard. Riwaqs are a continuation of the worship hall and the courtyard is also a worship place. However, masonry arches, instead of horizontal wooden beams, came to be built across columns, the continuation of arches and their above small walls came to emphasize the boundary of the courtyard. Furthermore, since Ottoman mosques clearly separated the worship hall from the courtyard (rather forecourt) as spaces, the courtyard came to be surrounded by galleries like Western abbeysf cloisters. To begin with, European cloisters originated in the ePatiof of Arabic architecture brought to Spain and the courtyards of ancient Roman houses. On the other hand, Persians introduced Iwans into the Arabic type mosquesf courtyards. The Iwan is a large, arched opening framed square by an upper wall with its inside space covered with a half dome or a semi-cylinder vault, becoming a half exterior space despite being roofed. Its origin goes upstream to the Sassanid Persian palacesf half outside living or audience spaces, much earlier than the advent of Islam. At the remains of Ardashir Ifs palace from the 3rd century at Firuzabad, a great Iwan spanning close to 13 meters can be seen.

Ancient Iwans in Firuzabad and Taq-e Bostan Persian Islamic architecture inherited this element, using it at the center of the facade of the worship hall in a mosque to emphasize the central axis toward the Mihrab at the outset. It gave a strong accent to the monotonous arcade of the worship hall facing the courtyard. Such brilliant Iwans were applied to not only mosques but also palaces and houses as well as madrasas and mausoleums, in short, almost all buildings in the Islamic sphere to function for various usage, providing a pleasantly shaded semi-outdoor space. For mosques, Persians placed Iwans not only on the Qibla (direction to Macca) but also on all faces enclosing the courtyard, inventing the eFour-Iwan typef mosques, and along with a symbolic central dome on the worship hall, they established the ePersian-type mosquef that is far more articulated and distinguished than the eArabic-typef mosque.

Although the classical mosque type was only the Arabic-type, three empires (Ottomans in Turkey, Mughals in India and Safavides in Persia) divided the Islamic world into three in early-modern times, and gave birth respectively to distinguished architectural styles, drawing up these four dominant types up in parallel. As being judged from the introduction of Iwans to mosques, the Persians can be said to be much showier than the Arabs, placing a high premium on beauty on the surface of everything. What shows this conspicuously is the upper part of Iwans and Pishtaqs. While their fronts are colorfully decorated with faience tiles, their rears are bare backstage structures without any treatment for beautiful appearance. Their objective was only displaying the splendid facades. It might be a precursor to modern signboard-architecture, which raises a high signboard on the facade of a commercial building.

The dome and a hypostyle hall of the Friday Mosque

Although the decoration on Islamic architecture is fundamentally plane patterns, there is also another original Islamic method of ornamentation, deviating from that. As it gives an impression as if it were stalactites in a limestone cavern or a large-scale honeycomb, it is called stalactite decoration or honeycomb vaulting in English, but intrinsically eMuqarnasf in Arabic. Muqarnas is comprised of numerous three-dimensional geometric parts of projection and depression with concave and convex curved surfaces.

Muqarnas of the Lotfollah Mosque, Isfahan Where did such a peculiar decoration come from? Its primitive origin is said to have been in the form of squinches supporting brick domes at four corners. In the Friday Mosque of Zavareh, each squinch arch has an unstable trefoil-arch inside, which can barely stay there because the load of the dome is not borne by it but by the squinch arche, small arches on both sides are inclined forward but not so much, and joint mortars bind these parts not a little. The overall formation by these elements, together with rear vertical small arches, carry out an extremely intricate but geometric three-dimensional artistic effect.    Squinches of the Gonbad-e Khaki & the Friday Mosque of Zawareh This skillful way can also be seen in the north dome (Gonbad-e Khaki) of the Friday Mosque of Isfahan and was carried out on an extensive scale at the western Iwan of the same mosque, spread to the entire half-dome ceiling on a square plan. Forwardly inclined pointed arches lean to each other at right angles, inside containing two curved triangles each. They pile up successively one over the other, composing a bold three-dimensional formation that had never been seen by anybody before.

Muqarnas of the West Iwan of the Friday Mosque, Isfahan As a brick-piling work without a finishing coat, this is a real masonry structure, but if the bricks had been piled with dry joint, those forwardly inclined pointed arches in the air could not have successfully formed and it would have entirely collapsed. With the assistance of the adhesive force of mortar joints, it became a narrowly actualized masonry work. When those elements were further fractionated and composed a plane, it then became a geometrical ceiling as if it were a honeycomb or stalactites, fascinating people in the Islamic sphere. It became widely popular after the 12th century, such as in the above-mentioned Shaikh Lotfollah Mosque in Isfahan. By applying this method to a ecorbelled structuref, which piles cut stones horizontally then protrudes upper stones little by little, it became a standard manner to give a sculptural expression to the overhanging part of balconies of minarets in Egypt and Turkey. Like this, in the estone-culture spheref (Egypt, Syria and Turkey) was developed stone Muqarnas of intricate and powerful shape for domical ceilings, pendentives, Pishtaqs, and Iwans, clearly expressing the flow of the force of gravity.

However, in Persia and Central Asia, as part of eearth-culture spheref, a different kind of Muqarnas was developed. It separated from masonry structure, devoting itself solely to the role of surface ornamentation. In the cases of brick Muqarnas in corbelling structures, their rough shapes and surfaces were often covered with stucco and painted or carved finely, and furthermore set with glazed tiles for their visual effect. If it was acceptable to conceal the structural material like that, wouldnft it have been the same to separate the Muqarnas from the structure? And suspend the surface of Muqarnas from it?

Thus, Muqarnas came to be disjoined from the structure and their lightweight surface panels made of painted stucco or tiled gypsum were suspended from brick vaults or domes. By this manner, it came to be possible to make any fantastic stalactites, honeycombs or surrealistic shapes as Muqarnas as was desired.

Muqarnas under restoration and Alhambra Palacefs Muqarnas

On half ruined or under repair Muqarnas, which were often seen in erstwhile Iran, we were able to observe the rear of Muqarnas that were suspended from brick vault with the assistance of timber, occasionally with I-steel or L-steel. In Islamic architecture, there is no other example of such a large estrangement between the first and second elements of a building, structural and ornamental.

Isfahanfs Friday Mosque has older, i.e. more subdued, ornamentation than the Royal Mosque in Isfahan. One aspect is concerned with colors: it exposes piled bricks more often than the other, except those facing the courtyard, which were tiled in various ways from early bricks glazed on only one side to later large multi-colored faience tile panels, for they were worked by various dynasties from Seljuks to some centuries later Safavids. They have much more archaic tastes than the Lotfollah Mosque or the Royal Mosque, and their etile mosaicsf made by cutting pieces from single colored tiles to make foliage and geometric patterns, are worth seeing minutely.

What is also subdued and worth to see is ceilings of each bays demarcated with four columns in various hypostyle halls, which were added by various dynasties. They are varied archaic brick domes reflecting the ages of their construction, interesting us deeply.   A part of the Riwaq walls and the Mihrab of Urjaitu

i2019 /03/ 01j |