|

MAUSOLEUM of QABUS

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

|

MAUSOLEUM of QABUS

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

In Iran was developed the form of tomb towers for kings and nobles, among which the earliest and highest is the mausoleum of Qabus, or Gonbad-e Qâbûs in Persian, built in 1006/7. It is not only the best representative of tomb towers but also one of the magnum opuses of Iranian architecture and would surely fascinate contemporary architects. It is a pure plastic formation of geometrical elements, entirely made of burnt brick, with few decorations. It soars 51 meters high on the plain of Golestan with overwhelming impact and charm. Its design would pass for a modernist work, 1,000 years preceding modernism.

Qabus was a monarch (r.978-1012) of Ziyar dynasty (930|1090) which had been established by an Iranian tribe, Daylamites, inhabiting the mountainous region on the south of the Caspian Sea. The name of the dynasty was derived from the founder, Ziyâr.

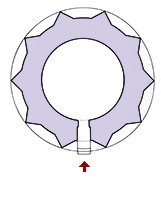

Plan and cross section of the Mausoleum of Qabus, 1006/7

According to Arthur Upham Pope in his own book, Qabus was an extraordinary man: a scholar and patron of scholars, a poet and patron of poets, a calligrapher, astrologer, linguist, chess player and doughty warrior. He is said to have had notable scholars Ibn Sina and Al-Biruni attend his court. However, his severe political reign might have aroused peoplefs antipathy.

The start of construction was in the early phase of the ePersian Renaissancef, which launched around the 10th century after independence from the withering Abbasid dynasty in Baghdad. As Persian architecture was not yet established, and being a precursor of the tomb tower, which was going to develop in Iran, it was an extraordinary happening to erect a brick tower as high as 51 meters without precedent and subsequent examples. Furthermore, fact that the place was in a remote field, 3km from a pivotal city, some people doubt it being the real tomb of Qabus.

As I wrote in the page of "Jantar Mantar in Jaipur", the enactment of the calendar was an important work of the ruler of government. There is a view that, like the huge instruments in the later Maragheh Astronomy in the 13th century or the Samarkand Astronomy in the 15th century, Qabus would have also ordered this tower constructed as an enormous astronomical observation facility. n the field of Islamic architecture, tomb architecture bore numerous masterpieces, next to mosques in number. Roofed tombs are called mausoleums, which were not rarely made grander and more luxurious than Friday mosques in the eastern Islamic sphere. There are two kinds of mausoleums; one for saints, considered as religious architecture as a subject of worship (Ziyâra), while the other for kings and nobles is secular architecture as a monument to give them authority or honor, though there are no difference of architectural style between the two. Furthermore, since both are composed of almost the same architectural vocabularies as in mosques and madrasas, even kingsf mausoleums look like religious buildings.

Mausoleum of Qabus, inside and outside The erection of mausoleums in the Islamic sphere was largely the influence of Christian society, in which mausoleums of saints called martyriums were frequently built in various places in early times, but later great martyriums were not developed for either saints or monarchs. Compared to this, Muslimsf enthusiasm for erecting large mausoleums seems excessive, or rather peculiar. Why had they showed such favoritism for great mausoleums? Moreover, Muhammad did not like that custom and early Islam prohibited the erection of mausoleums and going to worship at graves. Erecting mausoleums for saints and visiting them is equated with the cult of personality. Having worship subjects other than God was and is the fundamental infringement of the monotheism of Islam. Thatfs why Muhammad strictly blamed those deeds and Muslims were always buried in plain frugal tombs during the first two centuries of Islam. As dead Muslims are never cremated (for being identified with being burned in hell) but buried in the ground, a tomb is made as a heap of earth on it. If it is a stone coffin, a flat stone can be seen on the ground surface, and a grave-post is stood on its head. All grave-posts in a cemetery are turned to the same direction, because every dead body is laid on its right side and with their faces toward Macca (Qibla). The Muhammadfs body was also like this, having been buried under the floor of a room in his house-mosque in Medina in 632 without any special embellishment. That was the practice of the doctrine of Islam: everyone is equal before God. It was when the Caliph of the Umayyad dynasty Walid I rebuilt the Muhammadfs house (the first mosque) into the large Prophetfs Mosque that Muhammadfs tomb became splendid. The current enormous mosque in Medina holds the mausoleum of Muhammad inside, which all pilgrims to Macca necessarily visit to worship, contrary to the intention of Muhammad himself.

Surface of the brick structure with lines of calligraphy Everywhere in the Islamic sphere was built a mausoleum of a saint, which became a pilgrimage spot. The causes of such popularity of mausoleums were firstly the tradition of faith to saints from the pre-Islamic period, secondly as while mosques were places mainly for men, women rather went to Mazar (Türbe in Turkey, Dargah in India), thirdly the development of Sufism bore many memorial places of venerable Sufi saints, and fourthly while people exclusively worship God in mosques, places for prayers and wishes were the tombs of saints who were considered to have spiritual power. Around a tomb of a saint were often added Khanqa (Dervishesf ascetic monasteries), Imaret (kitchens for the needy), mausoleums of succeeding Sufis of the same order, and so on. Such a religious complex was called Dargah or Maqbara in the eastern Islamic sphere. The Dargah of Nizam-ud-Din Auliya in Delhi and that of Muin-ud-Din Chishti in Ajumer are good representatives, to which crowds of worshippers never cease to go and pray every day.

Occasionally, people reside around a saintfs mausoleum, forming a village, an extreme case of which is the famous religious town of Moulay Idris in Morocco. Another typical case is the mausoleum of Ma Mingxin, who was not a simple saint but the leader of the largest Menhuan (Sufi sect) of Zheherenye in China, his mausoleum becoming the holy place for the followers of this religious order to tighten their spiritual unity. In China, the name Gonbad collapsed to Gombai or Gombei.

In Arabic a mausoleum is called a Qubba, which means dome, denoting that masonry domes were used to roof over tombs, owing to the shortage of timber in the Middle East. Its original form can be traced back to Zoroastrian temples in ancient Persia in the style of dome constructed on four arches as referred to as Chahar-Taq (Four Arches). Qubba is Gonbad in Persian and Kümbet in Turkish, all deriving from the same origin.

The extant oldest mausoleum in Islam is the Sulaybiyafs Tomb in Samarra, Iraq, an octagonal tomb chamber surrounded with an ambulatory and surmounted with a dome, though half ruined. Given that the origin of this form was the Christian martyrium, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem (687- 692) can be said to be the first Islamic Qubba through the same stream, although its function was not a tomb but a memorial shrine. Its splendid interior with glass mosaics seems as if it foretold later magnificent mausoleums. Nevertheless, the construction of full-scale mausoleums would begin in the 10th century. The 10th century 'Mausoleum of the Samanids', though small scale, lead the brick mausoleum to its completion at a dash. In the 11th century, conical roofed tomb towers came to be erected from northern Iran to Anatolia, among which the mausoleum of Qabus is the masterpiece with a very powerful figure 51 meters high. Such an early tomb architecture was brought from Central Asia and some scholars suppose the origin of tomb towers to be tent roofs of nomadsf dwellings. The formula of two-fold tombs, setting a cenotaph at the center of the mausoleum and the real tomb in its underground room, was also brought from the same region.

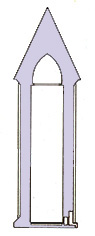

Erection of mausoleums thrived much further in the 12th century, and juxtaposition of them with mosques or madrasas also became popular. As mentioned above, mausoleums are intrinsically against the primary tenet of Islam, but the nations of Turkey and Mongol had a strong desire to revere and commemorate their ancestral deceased. The mausoleums of kings and nobles, constructed as national monuments with abundant budgets and competent architectsf designs, were sublimed into high architectural works. Deviating from original disposition of Islamic architecture as being introvert and membranous, desires toward buildings, which attach great importance to external appearances in the eastern Islamic sphere, ) made extreme development of mausoleum architecture, creating masterpieces like the Gur-e Amir in Samarkand, Humayunfs Tomb in Delhi, the Taj Mahal in Agra, and so forth. These were made with double-shell domes, reinforcing furthermore their monumentality. Occasionally were there monarchs who did not like such tides, wishing to be faithful to Muhammadfs precept. The 6th emperor of the Mughal dynasty Aurangzeb was buried in a frugal tomb only surrounded with walls, according to his testament. However, as this is an exception, most people in power were inclined to show off themselves, often preparing their mausoleums during their lifetimes. As far as the mausoleum being Qubba, they are domes on square plans, allowing not so many architectural variations. Generally, it did not take a courtyard style. In India, it was built like a sculptural work at the center of a vast Chahar-bagh (four quartered garden). In Egypt, it was often combined with a Madrasa or Khanqa, with a dome on a part of the aggregation. The Seljuk Turks constructed small-scale Kümbets with Armenian-like conical roofs descended from tomb towers, in the form of two-fold tombs with a domical ceiling over the tomb chamber.

Mausoleums of Jinnar (Pakistan) and Atatürk (Turkey)

Even in modern times, mausoleums were erected. The founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnahfs Mausoleum (1960-71) in Karachi is a Qubba, while the Mausoleum of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1944-53), the founder of the Republic of Turkey, in Ankara does not have a dome, suitable for the president who separated religion and politics, rather being akin to a Greek temple. As for Iran, Sassanian Persia was conquered in the middle of the 7th century by the army of Islam and for two centuries from this time forward was ruled by Damascus of the Umayyad dynasty and Baghdad of the Abbasid dynasty. The glory of the ancient Persian Empire thoroughly collapsed and its 7th and 8th centuries are designated as the ePersian Silent Centuriesf. All mosques from the Umayyad dynasty were lost, while leaving only one mosque from the Abbasid dynasty: the Tarik Khane Mosque in Damghan, the oldest extant mosque in Iran.

With the passage of time from the age of Muhammad, Muslim buildings gradually became more splendid to express the authority of Caliphs, Sultans, and other powers. Persians developed faience tile to embellish plain bricks, even exploiting Muqarnas decoration that was detached from a structural role, while Indians converted mosques and mausoleums into extrovert sculptural monuments.

Among such buildings, as with restrained ornamentation, the most strikingly impressive one is the Mausoleum of Qabus (Gonbad-e Qabus) near Gorgan, Iran. It is a brick tomb tower based on a star-shaped plan with a line of calligraphic inscription at the top and near the bottom of its outer wall as its sole adornment. Its outer protruding structural ribs, or to say buttresses, also function as restricted ornamentation. Overall, it is a powerful but slender geometric piece of architecture. There is a legend that Qabusfs body was put in a glass coffin and was suspended by chains inside the tower. An excavation in 1899 by a Russian team was not able to find his corpse underground, somewhat backing up this legend. If it is true, the purpose of it would have been not to disturb the posthumous peace of Qabus, though one might entertain a doubt whether it is compatible with the assassination of Qabus.

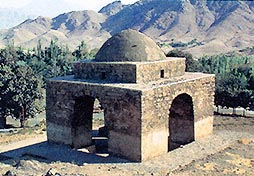

Be this as it may, let us look over the genealogy of the tomb tower developed in Iran. The mausoleum of Qabus, from the early 11th century, is one of the most incipient works of early Persian architecture, which includes many tomb towers in the provinces of Golestan, Khorasan and Mazandaran in northern Iran, though all small scale.

Tomb towers at Radkan and Bistam Next, a tomb tower in Bistam (Bastam) to the south of Qabus is the mausoleum of Abu Yazid Bistami, erected in the early 14th century. Its ribs on the wall are right angled as those of Qabus, but more crowded without intervals, making its dome look imbalanced, too small. Probably, this dome was a ceiling, over which would have been intended to build a conical roof. In that case, there could be a space between the double-shells, while the mausoleum of Qazan Khan, located nearby in the same town, has a triple-shell roof with spaces in between.

The foregoing examples showed that there are semicircular ribs and right-angled ribs in Iranian tomb towers. As these manners were brought to the east, the Qutub Minar belonging to the first mosque in India, Quwwat-al-Islam Mosque, combined these two with right-angled ribs on the third story, semicircular on the second, and mixed on the first, expressing an attractive variety. If the top story had been a conical roof, the tower could have been more captivating.

Qutub Minar in Delhi & Tomb Tower in Damghan In Damghan, 90km south of Gorgan, is the mausoleum of Cheher Dokhtaran from the middle of the 11th century, i.e. half a century later than the Qabus, in 1054. It has no ribs on the wall and is surmounted with a bullet-shaped roof, an intermediate form between a dome and a cone. It can be said to be in the age of groping the proper form for Iranian mausoleums. Damghan also has one more mausoleum, Alamdar Tomb, built in 1026, almost contemporary but larger than the former, also without ribs on the wall and surmounted with a semicircular dome. In a suburb of Damghan, Mehmandust, is also a brick tomb tower named Gonbad-e Masum Zadeh, erected in 1096 of the Seljuk dynasty. Its plan forms a dodecagonal star-shape with shallow triangle ribs. Its lost roof is supposed to have been conical like the Qabus and the part of the drum just under the roof is quite decorative with belts of muqarnas, calligraphy and geometry without a respite, in contrast with its lower wall, which is balmy, only accented with modest ribs.

Tomb Towers at Mehmandust & in Qazvin

A good example is the Gombad-e Hamad-Allah Mustafi in Qazvin, to the west of Tehran, erected in 1350 in the Mongolian ruling period. Its conical roof of blue-green glazed brick is splendid still now, with accents of a belt of tiled muqarnas underneath the roof and a calligraphic blue-colored tiled belt at the top of its drum.

Then, where could the origin of the conical roof of Persian tomb towers have been? It is Armenia, I consider. It was from the 5th to 7th centuries that Armenian architecture first flourished as a Christian architecture, in Vagharshapat as the start, around eGreat Armeniaf that occupied a much broader area than that of the current Republic of Armenia. It made up a unique church form, putting a dome over the crossing of the cruciform plan, and surmounted with a conical or pyramidal roof over the dome. That conical roof was used for Persian tomb towers.

Then, the Persian conical roof penetrated Turkey. In the city and cemetery of Ahrat, Turkey, many Kümbets (mausoleums) surmounted with conical roofs can be seen. Seljuk Turkey got into a habit of making mosques of flat roof type and mausoleums of conical.

Lastly, commenting upon the influence of Armenian conical roof to the east, it entered India via Central Asia. Many Himalayan wooden temples form multi-storied towers with a conical roof on the top. The Parashar Rishi Temple is a typical example.

i 2009 /02/ 01 j |