The Japanese Army, one million strong, has already conquered Jiangnan. We have surrounded the city of Nanking ... The Japanese Army shall show no mercy toward those who offer resistance, treating them with extreme severity, but shall harm neither innocent civilians nor Chinese military personnel who manifest no hostility. It is our earnest desire to preserve the East Asian culture. If your troops continue to fight, war in Nanking is inevitable. A culture that has endured for a millennium will be reduced to ashes, and a government that has lasted for a decade will vanish into thin air. This commander-in-chief issues a warning to your troops on behalf of the Japanese Army. Open the gates to Nanking in a peaceful manner, and take the aforementioned action.1

The "aforementioned action," described elsewhere in the leaflet, involved delivering the response to the warning, by 12:00 noon on December 10, to the sentry line on Zhongshan Road or Jurong Road. Commander-in-chief Matsui added that if no response was forthcoming, the Japanese would have no choice but to attack Nanking.

An organization chart and a staff list 2 are appended to Source Material Relating to the Battle of Nanking, Vol. 1. On the CCAA Headquarters staff list is a name that one normally would not expect to find there. The listing reads: "Saito Yoshie, Doctor of Law, advisor on international law." Matsui must have consulted with Dr. Saito whenever the need arose. By having the leaflets dropped on Nanking, the commander-in-chief was acting in full accordance with international law.

The Hague Convention of 1907 Concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land 3 was signed at The Hague, Netherlands in October 1907. Article 26 of Regulations Annexed to the Convention (effective in Japan as of 1912) dictates the issuance of a warning before initiating hostilities.

The officer in command of an attacking force must, before commencing a bombardment, except in cases of assault, do all in his power to warn the authorities.

Commander-in-chief Matsui was in complete compliance with Article 26 and with the "Nanking Invasion Outline" issued on December 7, when he advised military authorities in Nanking to surrender.

Article 27 of The Hague Convention Regulations Strictly Observed Article 27 of the aforementioned Regulations Annexed to the Hague Convention, which concerns restrictions on bombardment, reads as follows.In sieges and bombardments all necessary steps must be taken to spare, as far as possible, buildings dedicated to religion, art, science, or charitable purposes, historic monuments, hospitals, and places where the sick and wounded are collected, provided they are not being used at the time for military purposes.It is the duty of the besieged to indicate the presence of such buildings or places by distinctive and visible signs, which shall be notified to the enemy beforehand.

There was a distinct difference between the actions taken by the Chinese and Japanese forces vis a vis Article 27. Chinese troops, in their attempts to defend Nanking, set fire to nearly every city, town, and village on the outskirts of the city. They burned down some magnificent structures within the grounds of the Zhongshan Mausoleum, as well as the stately Ministry of Communications building. They incinerated nearly all of the Xiaguan district.

Conversely, Japanese troops observed the Regulations to the letter. In his article in the December 18 edition of The New York Times, Durdin wrote: "The Japanese even avoided bombing Chinese troop concentrations in built-up areas, apparently to preserve the buildings."4

Before they attacked Zijinshan (Purple-and-Gold Mountain), Japanese military personnel had been ordered by Commander Matsui "not to destroy the Zhongshan Mausoleum,"5 as Shimada Katsumi, a company commander, later testified. Consequently, they refrained from using their field guns, accomplishing the attack using only machine guns and rifles. International law was strictly observed, but not without considerable sacrifice, since a great number of Japanese soldiers were killed or wounded during the assault.

The International Committee Proposes an Armistice When the Japanese issued their final warning, a final attempt to stave off hostilities in Nanking was being made within the city. On December 9, the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone drew up an armistice proposal, which it submitted to Chiang Kai-shek. The proposal requested that the Japanese enter Nanking peacefully after Chinese troops had withdrawn from the city, also peacefully. Before those actions could take place, a temporary cease-fire, which the Committee proposed to both the Japanese and Chinese military, would be necessary.As for the length of the proposed cease-fire, there is a discrepancy of one day between an account (dated January 20, 1938 and written by Georg Rosen, secretary at the German Embassy in Nanking in The Sino-Japanese Conflict, a collection of official documents from 1937 to 1939 prepared by the Embassy)6 and an article in the Chicago Daily News submitted by Steele.7 Nevertheless, the cease-fire was to last for a maximum of three days.

However, all of Nanking's gates had been closed. The armistice proposal never reached the Japanese, but its content was identical to that of the leaflets they had air-dropped. It is likely that, if they had received it, the Japanese would have consented, but since they had not, its fate rested on Chiang Kai-shek's decision.

The Committee's proposal was telegraphed to Chiang from the American gunboat Panay and from the U.S. Embassy. However, as the International Committee had feared, Chiang rejected it.

Attack on Guanghua Gate The deadline for the response to the final warning from the Japanese was 12:00 noon on December 10. Major-General Tsukada Osamu (CCAA chief of staff) and Major Nakayama Yasuto waited for an emissary from Tang Shengzhi bearing a flag of truce. As a precaution, they waited an additional hour after the deadline had passed, until 1:00 p.m. No emissary ever appeared.The Japanese assumed that the Chinese had resolved to resist to the bitter end. According to an entry in the diary of Yamazaki Masao, staff officer of the 10th Army, they "realized that the enemy had no intention of surrendering,"8 and decided to launch a general offensive at 2:00 p.m. on December 10.

The general offensive was conducted in accordance with the "Nanking Invasion Outline" dated December 7. Japanese troops had been ordered to seize the gates by bombarding them if the enemy "should refuse to leave their bases at the city walls,"8 and, once they had passed through the gates, to sweep Nanking. They were never ordered to engage in random attacks on civilians.10

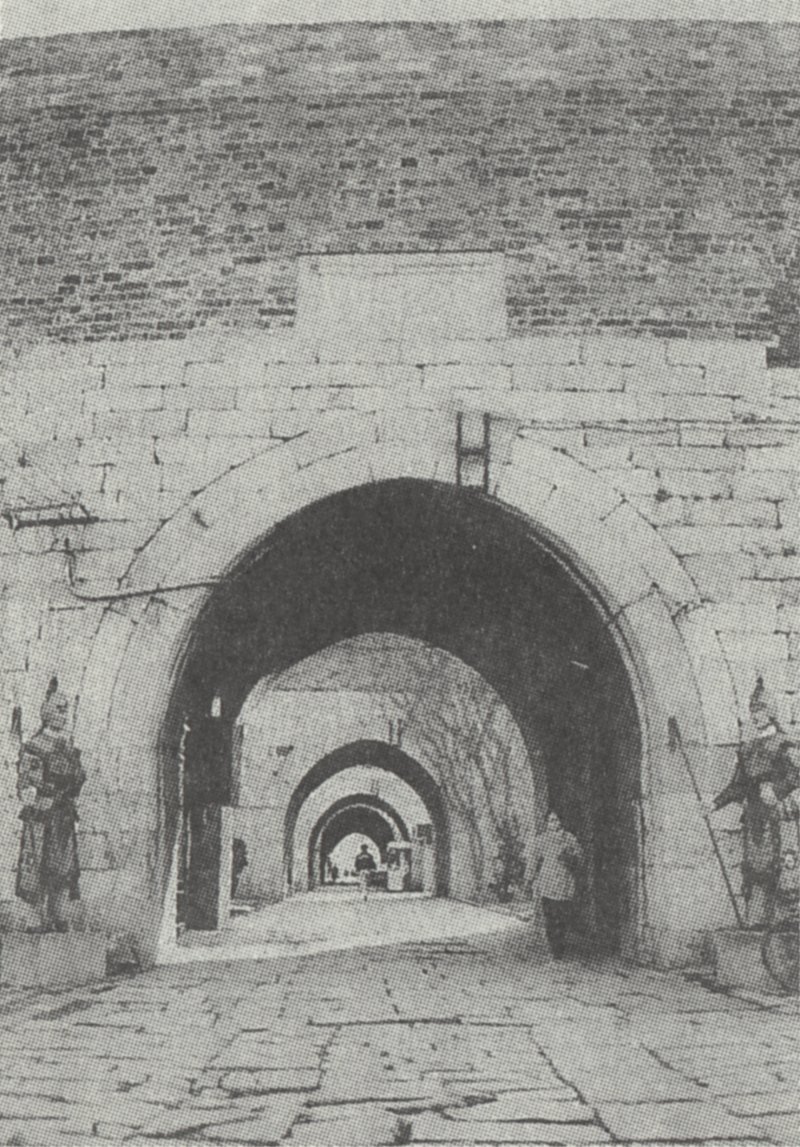

The gates were the first obstacles, and they were formidable ones. There were 19 of them in Nanking, including two railway gates. The gates facing south from the east became the arenas for the heavy fighting that ensued. The first gate reached by Japanese troops was Guanghua Gate, situated between Zhongshan Gate (East Gate) and Zhonghua Gate (South Gate).

At dawn on December 9, the 36th Infantry Regiment, attached to the 9th Division from Kanazawa, fought its way to Guanghua Gate after a forced march lasting several days and nights. According to The Battle of Nanking (published by Kaikosha) and the 36th Infantry Regiment's "Report on Operations in Central China," the wall in which Guanghua Gate was situated was approximately 13 meters high. In front of the wall was the outer moat, approximately 135 meters wide. Guanghua Gate was actually a double gate, with outer and inner archways, and iron doors. The two archways were about 20 meters apart.11

Anti-tank trenches and five rows of chevaux-de-frise blocked the road leading to the gate. The muzzles of machine guns protruding from loopholes on top of the walls were aimed directly at Japanese positions.

The attack on Guanghua Gate commenced at 2:00 p.m., after the deadline for surrender had passed. But the gate was so solidly built that they could make little headway. Soldiers made desperate charges against the wall, only to be killed, one after the other.

According to the recollections of Cheng Huanlang, a Chinese staff officer, found in Source Material Relating to the Battle of Nanking, Vol. 2, on the night of December 10, when the assault on Guanghua Gate began, "a battalion from Deng Longguang's unit, sent as reinforcements to Guanghua Gate, arrived with some farmers, carrying some dozen severed enemy heads in bamboo vegetable baskets ... proclaiming victory."12 Even farmers had been enlisted for the defense of Guanghua Gate. This was clearly a violation of international law, which prohibits the mobilization of noncombatants.

Japanese troops began firing their mountain guns, and finally succeeded in demolishing part of the gate. Portions of the wall crumbled, the debris forming a steep hill. The 1st Battalion ascended that hill and, at last, broke through and seized the outer gate. By the time the Japanese flag had been raised amidst the rubble, night had fallen.

Guanghua Gate was defended by Chiang Kai-shek's elite supervisory unit. The day after the gate had been partially destroyed, Chinese forces were doubled in size, to 1,000. Barricades of sandbags covered with barbed-wire entanglements had already been erected on the periphery of the gate. Furthermore, machine guns were aimed at the Japanese by Chinese soldiers protected by impregnable concrete pillboxes.

Outside the city, at Zijinshan (northeast of Guanghua Gate) and Yuhuatai (south of Zhonghua Gate), Japanese and Chinese troops were locked in a desperate struggle. The Nanking Defense Corps, aware that if Guanghua Gate fell to the Japanese, hostilities outside the city would, within a short time, be pointless, were motivated to fight even harder.

The Chinese brought in tanks, from which they fired on Japanese soldiers inside the outer gate, immobilizing them. Then the Nanking Defense Corps began strafing the Japanese from the top of the gate. Next came an incendiary attack: the Chinese threw lumber down on the Japanese, and poured petroleum on it, which they then ignited. The 1st Company was trapped inside the outer gate. The 88 Japanese soldiers there fell, one after another, till only eight remained. They were saved from total decimation by Japanese heavy artillery, the firing of which commenced on the morning of December 12. Gradually, the Japanese gained the upper hand. Finally, at 6:00 a.m. on December 13, the Sabae Regiment occupied Guanghua Gate.

It had taken the Japanese three full days to occupy the gate in one of the fiercest, bloodiest battles waged in Nanking, involving much hand-to-hand combat, with both sides hurling hand grenades at each other. Ouchi Yoshihide described the hostilities in his testimony at the Tokyo Trials.

On the morning of December 13, we occupied the wall of Guanghua Gate, but were not permitted to enter the city. The military police and a few small units entered Nanking. That day, the charred bodies of some unidentified men were found near the wall. They were still breathing, but just barely. When he saw them, Major Haga, the battalion commander, was furious. He ordered an immediate search for the perpetrators. I halted my battle preparations, and assembled my subordinates. I gave them instructions, and conducted an investigation, but discovered that none of them had been involved.The medical officer who examined the bodies said that the crime had been committed at least 10 hours previously - before Japanese troops entered the city. He determined that the victims were Japanese soldiers who had been taken prisoner by the Chinese and set fire to. That same night, I returned with my unit to Tangshuizhen.13

Ouchi was a second lieutenant in the 9th Division, 9th Mountain Artillery Regiment. According to his testimony, the Chinese had taken Japanese soldiers prisoner during the peak of hostilities at Guanghua Gate, and burned them alive. However, the Chinese could not be accused of cruelty to prisoners of war (a violation of international law). This was war, and it was kill or be killed.14

Stone steps formed a gradual stairway from the base of Zhonghua Gate to the top of the wall. Parallel to the stairway was a gently sloping ramp, also leading to the top of the wall, designed for transporting cannons. Across the top of the wall, right at the end of the stairway, stretched a vast plaza. At the highest point on the wall were rectangular holes (loopholes) set at specific intervals, through which Chinese soldiers could fire their guns at targets outside the city walls, where there was no shelter.

Outside the gate was the Qinhuai River, an artificial waterway excavated under orders from the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty, which served as an outer moat. Slightly downhill from Guanghua Gate, the Qinhuai converged with the Hucheng River. Near Zhonghua Gate, the Qinhuai was 30 meters wide and three meters deep.

The 6th Division from Kumamoto was entrusted with the assault on Zhonghua Gate. On the night of December 10, the Division's first priority was attacking Yuhuatai, located south of the gate, on which it concentrated all its resources. It penetrated Yuhuatai at dawn on December 11. Not until 24 hours later, however, was the 6th Division able to reach the Qinhuai River, the moat outside Zhonghua Gate.

Before they could attack Zhonghua Gate, 6th Division soldiers first had to ford the outer moat. They built a temporary bridge, but the Chinese soldiers on top of the gate fired on it, and it soon collapsed. With the help of an artillery unit, the Japanese began bombarding Zhonghua Gate. First they demolished the southwest corner of the gate, and eventually succeeded in opening two breaches in the wall. At 4:45 p.m., they occupied the breaches and, subsequently, the top of the wall.

At 1:00 a.m. on December 13, they occupied the front of Zhonghua Gate.16 At 3:00 a.m., they removed the stone blocks that had been packed tightly into its archways. The bridge in front of the gate, however, had been demolished. On December 14, after another temporary bridge had been constructed, Major Yamazaki Masao crossed it on foot and entered Zhonghua Gate. Yamazaki described the situation at the gate, after another pitched battle, in his war diary.

December 14: Corpse upon enemy corpse near the gate - a pitiful sight. Our men and the moat in front of the gate, and behind it a wall and a tightly closed gate. The enemy can neither advance nor retreat, and will surely be annihilated.17

I believe it was the evening of the 13th when we entered Nanking from the South Gate. The ground was littered with the dead, both my comrades and the enemy. Among the bodies I saw the corpse of a Japanese soldier who had been tied to a tree and shot several times. I assumed that he had been taken prisoner by the Chinese and then slaughtered. I cut the ropes and laid his body on the ground. Near the city walls, there were a large number of dead Chinese soldiers, but I saw no civilian corpses. ... On December 13, I returned to Tangshuizhen, and then led my unit to Tushanzhen, south of Nanking, where we regrouped. At that time, I forbade my men to leave the area, in accordance with orders from my superior.18

Osugi was the head of an observation party from the 1st Battalion, attached to the 3rd Division, 3rd Field Artillery Regiment. He was also the officer who had been ordered to reconnoiter the battlefield subsequent to the attack on Nanshi in Shanghai (one month prior to hostilities at Nanking), to ensure that Japanese shells had not hit the French Settlement. He was ordered to do reconnaissance work again after the attack on Nanking. Osugi entered the city from the South Gate.

It was then that he saw the Japanese soldier who had been taken alive and brutally executed. But the Japanese could not claim that the massacre of a prisoner of war was in violation of international law. In the midst of a battle, it was impossible to accommodate prisoners.

Tang Shengzhi Decamps At 8:00 p.m. on December 12, several hours before Zhonghua Gate (South Gate) and Guanghua Gate (Southeast Gate) fell, the commander-in-chief of the Nanking Defense Corps decamped. Despite having declared that he would defend Nanking to the death, Tang Shengzhi forsook his subordinates and escaped from Xiaguan to Pukou, on the other side of the Yangtze.One wonders what Tang expected his men to do from then on. All the city's gates were closed, with the exception of Yijiang Gate, where the supervisory unit was posted, under orders to shoot deserting soldiers.19 Having been abandoned by Tang Shengzhi, troops inside the city were trapped, with only three options available to them.

(1) They could have fought to the last man, but this was not a viable option. Once Tang had decamped, it is unlikely that anyone would have obeyed orders to that effect. Furthermore, it was common practice for Chinese soldiers, in the face of defeat, to remove their uniforms and masquerade as civilians. (2) They could have fled Nanking before it fell. But since the gates were closed, there was no escape route available to them. Perhaps 40 or 50 soldiers could have escaped from the city walls, but not many more. (3) They could have escaped to the Safety Zone inside the city. This was the most realistic option, and it surely was contemplated before the decision was made to close the gates.In fact, 90 minutes before Tang decamped (6:30 p.m. on December 12), Rabe mentions, in his diary, that he personally witnessed Chinese soldiers who had been fighting at Zhonghua and Guanghua gates running toward the center of Nanking, as if insane.20 But as they neared the Safety Zone, they gradually regained their composure, and slowed their pace. Though it was never mentioned, there was a tacit understanding among Chinese soldiers escape to the Safety Zone was an option available to them.

No one knows how many surviving Chinese soldiers remained in the city. However, with the exception of those who had been fighting in the Safety Zone from the outset, those who were shot down by their own supervisory unit, those who died in battle, and those few who escaped from the city walls, Chinese troops infiltrated the Safety Zone.21

Thus, the Safety Zone, intended as a refuge for evacuees, became a haven for thousands (perhaps tens of thousands) of Chinese soldiers, primarily raw recruits - battle groups with no commander, no order, and no discipline. Soldiers who escaped to the Safety Zone were not acting spontaneously, but in accordance with an unspoken agreement, reached prior to the fall of Nanking.

Recruit Every Able-Bodied Man Source Material Relating to the Battle of Nanking, Vol. 1 contains a description of Tang Shengzhi's defense of Nanking. Apparently most of the soldiers were recruited in Nanking, since units retreating from Shanghai to Nanking had suffered so many casualties. As Tang himself admitted, he had very few trained soldiers. Most of his men were raw recruits.22 According to the Nanking Defense Corps Battle Report, "At the time, the Nanking Defense Corps comprised only the 88th Division, the 36th Division, the supervisory unit, and a military police unit. All of them had come from Shanghai, after fighting the Japanese there, and new recruits were added in Nanking." In this brief report, the term "new recruits" appears twice.23As Durdin reported, Chiang Kai-shek and Tang Shengzhi rounded up every able-bodied man.24 Therefore, the Japanese were surprised "to find no young men anywhere" when they entered the city, as Makihara Nobuo wrote in his diary.25

The Chinese military provided the conscripts with little, if any, training. Raw recruits who had never held a rifle, who had no idea of their responsibilities as combatants, were sent off to the battlefield, where they were compelled to learn how to wage war. This phenomenon was not peculiar to the Nanking conflict. As both Durdin and Steele reported, this was a traditional military procedure practiced throughout all of China.26 When recruiters found men of draft age in a farming village, they would tie their hands together, and lead them away.27

Since there was no training, there was no discipline and, therefore, a very fine line between regular army personnel and outlaws.28 Unsurprisingly, losing battles resulted in uncontrollable chaos. As we will discuss later, regular army personnel even removed their uniforms on the battlefield.

Nanking Defense Corps Suffers Major Losses The following account appears in the "Nanking Garrison Battle Report" reproduced in Source Material Relating to the Battle of Nanking, Vol. 1.Most of the units in the Nanking Defense Corps suffered tremendous casualties in battle. There were few seasoned soldiers. Raw recruits were sent to the frontlines with no training. Officers and their men were not able to recognize each other, so when they were hit by shell fire hit, they dispersed immediately, and could not be controlled.29

The Nanking Defense Corps' bitter experiences were partly due to Japanese aerial bombing and superior shell fire. But a far more significant factor was the quality of the Chinese soldiers, who had been placed in an unenviable position. Officers and their untrained recruits were meeting for the first time, so could not recognize each other. Once they were fired upon, they "dispersed immediately." One could hardly expect the Chinese to conduct an organized resistance under these circumstances. It is not surprising that the Defense Corps sustained "tremendous casualties."30 Most of the Defense Corps suffered "serious damage by battle."31 The consequences were of a seriousness that is impossible to overestimate. According to The Battle of Nanking, the Chinese forces were 60,000-70,000 strong. Of their numbers, 30,000 are assumed to have died in battle,32 and this is certainly not an exaggeration.

Chinese Soldiers Strafed by Supervisory Unit at Yijiang Gate Most of the Chinese soldiers in the crippled city are presumed to have removed their uniforms and infiltrated the Safety Zone. However, some of them headed north on Zhongshan North Road for Yijiang Gate (North Gate), which led to Xiaguan on the banks of the Yangtze. Yijiang Gate was the only open gate and, therefore, the only possible escape route. On the night of December 12, multitudes of Chinese soldiers rushed to Yijiang Gate, which had been fortified with timbers and sandbags. The following is an excerpt from the memoirs of Staff Officer Cheng Kuilang in Source Material Relating to the Battle of Nanking, Vol. 2.In front of the Ministry of the Navy on Zhongshan North Road, I saw units from the 36th Division standing on the road, having laid down their machine guns, and blocking traffic. They would not allow other units coming from the south to pass. ... Zhongshan North Road was soon filled with vehicles and soldiers, which stormed Yijiang Gate. In the desperate competition to escape from the city, they lunged forward in waves, only to be pushed back. Some of them were trampled, and I could hear them yelling, 'Grandfather! Grandmother!' The sentries with the 36th division had placed machine guns on the parapets on the wall, and were shouting, 'Don't push! We'll shoot if you push!' But the pushing and shoving continued.33

According to the Nanking Defense Corps Battle Report, the responsibility of the 36th Division was to use force to prevent units from retreating.34 This was a favorite tactic of the supervisory unit, and a Chinese specialty.

According to the Memoirs of Li Zongren, the supervisory shot at waves of fleeing Chinese soldiers from behind. Many of them were wounded or killed.35

False Reports Issued by American Journalists The realities notwithstanding, Durdin wrote the following report, and sent it off to The New York Times.The capture of the Hsiakwan [Yijiang] Gate by the Japanese was accompanied by the mass killing of the defenders, who were piled up among the sandbags, forming a mound six feet high.36

Later, Steele, who had left Nanking, wrote a similar report, stating that when he left Nanking from Xiaguan, his car had to drive over a five-foot-high pile of corpses. Japanese Army trucks and cannons also rode over the bodies. There were corpses of civilians on the road, which was also scattered with Chinese military equipment and uniforms.37

Both journalists were implying that the Japanese were responsible for the five-foot-high (or six-foot-high) mound of corpses. Reading these articles, one would get the impression that the Japanese had slaughtered Chinese soldiers en masse when the former occupied Yijiang Gate.

However, the Japanese were not involved in any hostilities at Yijiang Gate. When they occupied the gate, it was Chinese soldiers who strafed their comrades, killing and wounding a great number of them.

In 1987, long after World War II had ended, Durdin finally conceded that there was no battle between the Chinese and Japanese at Yijiang Gate. According to Nanking Incident Source Material, Vol. 1: American References, Durdin recanted, admitting that there was a confrontation at Yijiang Gate between Chinese soldiers attempting to escape. Some of them were trampled to death, and that was the reason for the mound of corpses.38 Steele, too, eventually spoke the truth (in 1986), admitting that a great number of Chinese soldiers suffocated while attempting to escape through Yijiang Gate.39

Both accounts placed the blame for hostilities among Chinese soldiers on Japanese troops. They were malicious reports, with no basis in fact. What Steele described as the bodies of civilians were probably those of Chinese soldiers who had shed their uniforms in an attempt to pass for civilians. The reason for his having made that assumption shall be discussed later on in this book. It is impossible to deny categorically that some of the corpses were those of civilians, but most of Nanking's noncombatants had already evacuated to the Safety Zone.

Main Strength of Chinese Military Escapes Some Chinese soldiers were either shot and killed by members of the supervisory unit or trampled to death. Others made desperate attempts to escape by lowering themselves on ropes from the top of the city wall. Many of them fell to their deaths.Even if they were fortunate enough to exit the city successfully through Yijiang Gate, there were no boats available to ferry them across the Yangtze. Some of the soldiers attempted to swim across the river. Others boarded makeshift rafts. Many of them drowned or were killed by machine-gun fire from a Japanese naval warship.

Thus, it would appear that the majority of Chinese troops were killed either inside or outside the city, but that was not the case.

When news of [Tang Shengzhi's] flight became known, the Chinese soldiers attempted to leave the city. They were mowed down by machine-guns in the hands of their own comrades, but, when it became apparent that the fall of the city was inevitable, all Chinese troops who could fled from the scene.40

This account from The China Journal (January 1938 issue) describes the situation in Nanking on the day before the city fell. The main strength of the defending Chinese units escaped Nanking alive. Many Chinese soldiers in the city infiltrated the Safety Zone. Soldiers fighting outside the city simply fled.

The flight of Chinese troops from Nanking is substantiated by other records as well. Every issue of The China Weekly Review included a "day-to-day summary constituting a complete record of outstanding events in the war on all fronts." The following descriptions of the movements of Chinese soldiers appeared in the January 29, 1938 issue.

December 21: Two Cantonese Divisions defending Nanking fought their way through Japanese lines into Anhwei [Anhui] province. December 22: Japanese reports that some 20,000 Chinese troops still in Nanking denied by Chinese military authorities in Hankow.41

These accounts must have been based on reports emanating from Chinese military authorities in Hankou. The main strength of the Chinese military had moved to Anhui, which is adjacent to Nanking, one week after the fall of Nanking.

The move had also been confirmed by the Japanese military. The December 16 issue of the Osaka Asahi Shinbun carried the following report.

In defending Nanking, defeated enemy units have broken through Japanese lines and have travelled along two routes, over land (the eastern line of advancement) and up the Yangtze River. They are assembling at Bengbu in Anhui Province and at Anqing (Huaiqing). Subsequent to the fall of Nanking, the enemy has been accommodating soldiers who survived hostilities there, and is building a major defense position in front of the mountainous region bounded by Anhui, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang, with concentration in Anqing. With these two lines of defense, the Chinese are preparing for another battle.42

This account is more specific than the one that appeared in The China Weekly Review. No accurate figures are available, but it is obvious that the majority of Chinese troops fled Nanking.