September 10, 2009

Getting to the top in tennis, stats say, is all about the return

By Douglas Robson

NEW YORK --- When Andy Roddick bombed his way to the 2003 U.S. Open title, it signaled the rise of another dominant server in a sport where first delivery always has been paramount to success. In reality, it signaled an anomaly in the evolution of the sport.

"I've said for a long time I'm the last real big server," says the fifth-ranked American, who clocked the fastest recorded serve at 155 mph.

Roddick isn't that far off.

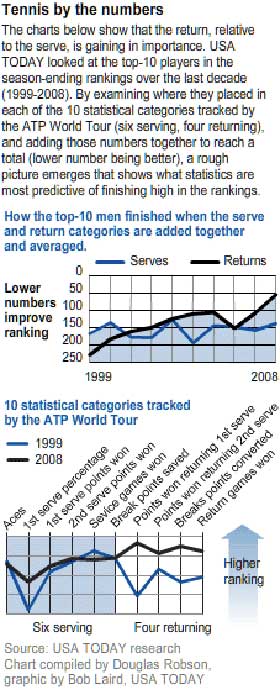

A USA TODAY statistical analysis of the men's tour over the last decade illustrates what has become increasingly conspicuous to students and casual observers of the game. The serve, relative to the return, has diminished in importance. But rarely, if ever, has it been statistically modeled.

Last year, for instance, the most accurate statistical barometer for predicting a top-10 finish in the year-end rankings came in two return categories: points won returning first serve, and break points converted.

In 1999 and 2000, by contrast, serving categories dominated, with service games won, aces and second serve points won most closely aligned with a high season-ending ranking.

"Players used to attack," says 15-time major winner Roger Federer, who launched his record-breaking career in 1998. "Now they defend more. (The analysis) just confirms what the feeling is of everybody."

Or as American Paul Annacone, Pete Sampras' former coach, says: "If you're a big server, it might not carry you as far as it used to."

Because the ATP Tour tracks only 10 statistical categories --- six on serve, four on return of serve --- the results are more an outline than a definitive picture.

Other factors, from advances in string and racket technology, to cyclical playing styles, also have a role. Still, the analysis shows how the game has evolved toward the baseline, even in the six years since Roddick captured his major in New York.

Stats back up belief

In the expanding era of Sabermetrics, Tennis lags behind many other sports when it comes to gathering and analyzing statistics. The ATP has tracked 10 categories only since 1991; the women's tour began tallying the same categories last October.

Like Federer, players, coaches and observers nodded in agreement when shown the findings. While they knew the pendulum had begun to swing away from serving, seeing a mathematical picture gave vision to what they were experience on the court.

"What does it show?" 26th-ranked Mardy Fish said. "Baseliners rule."

John McEnroe, the seven-time major winner from Queens, says he realized how much the game had morphed during the thrilling 2008 Wimbledon final, when Rafael Nadal defeated Federer in five sets.

In the four-hour, 48-minute final, the baseline-hugging spinmaster from Spain attacked the net three times in the final game --- once behind his serve for the first time in the entire contest --- a gutsy strategic departure from the norm.

"Who would have thought in their wildest dreams after watching the likes of (Boris) Becker, (Pete) Sampras and (Goran) Ivanisevic and seeing two guys playing the Wimbledon final --- arguably to me the greatest match that was ever played --- serving and staying back nine out of 10 times?" the Hall of Famer and TV commentator says.

By today's baseline-friendly standards, nine out of 10 might be generous. That doesn't mean the serve --- the only shot in tennis completely in a player's control --- is an afterthought. The stroke that begins every point is still crucial.

During the last decade, categories such as service games won and points won on second serve are strong and consistent indicators of success.

This season, six of the current top 10 rank in the top 10 for points won on second serve (Roddick leads with 57%).

But other service categories have diminished over time, notably aces and first serve points won, suggesting that outright service winners are of less consequence.

At the same time, more of the world's top 10 --- seven --- populate a return category (points won returning second serve) than any other.

'A lot more about legs'

Why has the serve diminished? Partly because of the new synthetic strings that allow players to take huge cuts at returns and keep the ball in play. The preponderance of two-handed backhands, which provides extra stability in returning, is another factor.

To Roddick, whose improved fitness and movement under coach Larry Stefanki carried him to a near Wimbledon victory and a return to the top five, the game has become more weighted to the lower extremities.

"It's become a lot more about legs and a lot less about actual shotmaking," says the 27-year-old American, who was upset in the third round here by compatriot John Isner.

One of today's best examples is Andy Murray, the British player whose unconventional, counter-punching style has propelled him to the No. 2 ranking. Entering the U.S. Open, Murray ranked first or second in all four return categories.

Murray, 22, hasn't been on tour long enough to measure any differences in the last decade, but he's noticed how the game has changed.

"When I was growing up and watching Wimbledon, all the top guys played serve and volley" and hit more aces, Murray says.

Murray, who like a lot of pros can uncork first serves above 130-mph, says better reaction times and improved equipment means deflecting even the hardest serves back into play is possible. That, in turn, has altered how players use their serve.

"Guys are not trying to hit aces necessarily with the first serve but going more for placement and trying to dictate play from the back of the court," he says.

It's not just technology and technique that have evolved; so have the players.

Jose Higueras, 56, who coached Michael Chang and Jim Courier to French Open titles and now oversees coaching for the USTA elite development program, says the legion of big serves has caused players to adapt. And adapt, they have.

"People get used to speed," the former No. 6 player from Spain says.

Top-ranked doubles player Mike Bryan says when Roddick came on the scene his 145-mph serves "would scare people."

So many players serve "bombs" today they have learned to adjust as a matter of survival.

"Everyone's eye is getting better," Bryan says. "(Roddick's serve) is still the biggest weapon in the game, but guys are returning it pretty calmly."

As much as eyes have changed, so have surface speeds. Grass, clay and cement are more alike than ever, making the sport a one-style-fits all proposition.

Wimbledon introduced a new grass composition in 2001 that has made it firmer, with more consistent, true and high bounces. Players contend it's also slower, but All-England Club officials say this is not the case.

Many players say the pace of hardcourts, on which most ATP events are played, have likewise been tamped down. Some say clay is faster. Others insist that balls used by the tour and at the four Grand Slams have slowed down (or in the case of Roland Garros, sped up).

"The Wimbledon ball is like a flipping grapefruit," quips Roddick's coach, the former pro Stefanki.

"It's not science fiction that the courts are slower now and it's more important to win a rally," former top-five player Ivan Ljubicic of Croatia says.

The upshot: Playing styles have narrowed. More aggressive returns, coupled with the slowly dying serve-and-volley a tactic, has made baseline play the dominant style.

This is taking place even at the developmental level, says famed tennis guru Nick Bollettieri, whose eponymous academy in Florida has spawned No. 1s from Andre Agassi to Maria Sharapova.

"The returners are so much bigger today, and the serve is somewhat neglected," Bollettieri says.

'Really, really physical'

With so few men crawling on top of the net after serves, the player who can get it back in play stands a better chance of staying in, and eventually winning, the rally.

"That's the most important stat --- returning the first serve and getting into the rally," agrees No. 4 Novak Djokovic of Serbia. "The surfaces are much slower, which gives more opportunities to the players who are physically very well prepared and whose games are based on the baseline. I'm one of them."

At 6-4 and one of the game's hardest servers, Ljubicic says he was forced to abandon the net-charging style that helped him reach the 1996 Wimbledon boys' final.

Five years after he joined the tour in 1998, the Croat says he had an epiphany when he came up flat in the semifinals of an indoor tournament in Basel, Switzerland, after two tough three-set wins, one against Federer.

"I realized if I have to do well, I have to run --- a lot," he says. He then hired a full-time physical trainer for the first time.

"This is what tennis has become: really, really physical sport," he adds.

Darren Cahill, the Australian pro who coached Agassi during the final years of his storied career, looked at USA TODAY's analysis and said it showed why players today fight ferociously for every point, whether they are serving or not.

"Now there is no safety zone in tennis," says Cahill, an ESPN analyst. "You can't just serve your way to a tiebreak these days."

A few, like Ljubicic, say the shifting importance of returns and attendant stylistic homogeneity has an aesthetic cost.

"Tennis has lost in my opinion a little bit of that intensity," he says, "because we all have to play the same way."