since February 24, 2002

|

|

Sri Lanka's bloody ethnic conflict has lasted nearly 20 years, claimed at least 70,000 lives and foiled every conceivable attempt to end it. Today, for the very first time, a negotiated, peaceful solution seems possible. The government and the rebels are close to declaring a one-year truce: no more jungle ambushes, suicide bombings, amphibious assaults. The divide between Tiger-held areas and the rest of the country is being opened up, allowing people to move freely again. Diplomats from Norway, the two sides' chosen negotiators, say the Tigers themselves have virtually given up their demand for a separate homeland and have agreed, if talks go well, to return to the fold. The cause is big changes on both sides of the war front. For the government, politics have taken a remarkably lucky turn. Friction between the country's two political parties helped create the problem with the Tamils in the first place and scuppered many a chance at peace in the past. But today, both parties are in power: the Sri Lankan Freedom Party's Chandrika Kumaratunga is President while rival Ranil Wickremesinghe of the United National Party is Prime Minister. Both admit the country can no longer afford ceaseless war. The fiscal deficit has soared to 10% of GDP and the economy is contracting as tourism declines and foreign investment collapses. In her Independence Day speech last week, Kumaratunga declared "a historic opportunity to evolve new systems of constructive cohabitation." Wickremesinghe condemned "divisive influences" and said he wanted to "awaken hope of peace." The Tigers' situation has changed even more dramatically

as a result of Sept. 11. The Tigers' feared leader, Velupillai

Prabhakaran, is unquestionably a freedom fighter, having waged

a relentless 19-year struggle to give the island's Tamil minority

its own country, liberating it from decades of discrimination

by the majority Sinhalese Buddhist population. But his vicious,

vengeful tactics now arouse opprobrium abroad. Prabhakaran's

Tigers, which include the most successful suicidal squads since

the kamikazes -- and a likely inspiration to the Sept. 11 terrorists

-- are now banned in the U.S., U.K., Australia and India. Each

of those countries has thousands of ethnic Tamils who secretly

financed the insurgency, and before Sept. 11, they operated freely.

Nowadays, they've gone underground and fund raising is much more

difficult. Neither Prabhakaran nor the government seemed able

to win the war militarily. But if Colombo asks for help from

the U.S. and the international coalition against terror, the

Tigers could be routed. "The changes in the international

scene since 9/11 and the banning of the LTTE have made Prabhakaran

realize he cannot continue in the same way," says Victor

Ivan, editor of Ravaya, a prominent Sinhalese weekly. Still, it's hard to imagine how a man who has lived as a guerrilla fighter since his teens will be able to give up jungle warfare for prosaic politics. Prabhakaran, 47, has agreed to many truces and peace talks in the past, always using the time to regroup, rearm and then go back to war. He is notoriously paranoid: there are rumors that he ordered the execution of some of his trusted lieutenants, fearing an internal coup. He lives in a 12-m-deep bunker, protected by his suicide squad of Black Tigers, which includes a female brigade known as the Birds of Paradise. He has not been seen in public for nearly a decade. His followers and victims alike receive only one message from him yearly, in a Martyrs' Day speech broadcast by the rebels' clandestine radio service. Last November, however, instead of his usual war cries, Prabhakaran tried to win international approval. "We are not terrorists," he announced. "We are fighting and sacrificing our lives for the love of a noble cause, that is, human freedom." Few governments see the Tigers in that light. Prabhakaran is wanted for murder in India because one of his Birds of Paradise detonated a bomb tied around her waist to kill then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1991. In Sri Lanka, the LTTE is held responsible for numerous assassinations: killing a President, several ministers and, 14 months ago, sending a suicide bomber to wipe out President Kumaratunga, who survived but lost the sight in one eye. Nonetheless, Prime Minister Wickremesinghe told TIME that if Prabhakaran were willing to come in from the cold, the government would pardon all his sins and those of his followers. Despite fear of violent protests by majority Sinhalese chauvinists, who have already begun campaigning against the peace efforts, Wickremesinghe says he is ready to negotiate anything but outright secession. "We are willing to go as far as possible for a solution while safeguarding the territorial integrity of Sri Lanka," he says. "We want a solution that protects the interests of all sections of our people." By opening the front line at Piramanalankulam and elsewhere, the government hopes to win some Tamil hearts and minds by allowing supplies to get through, prices to drop, a gust of freedom to blow. That, however, is an uphill battle. Although tired of war, Tamils have not forgotten years of slight by the majority Sinhalese who make up 72% of the population. Many Tamils who have experienced the LTTE's autocratic rule haven't turned their backs on them or their cause. "I neither support nor oppose the Tigers," said 26-year-old farmer Muthu. "I am just controlled by them." Murugan Veliyar, 71, says he was forced to stay in his village of Vanni to function as a human shield against attack by government forces. Even so, Veliyar still wants an independent Tamil homeland. "Otherwise," he says, "it will all have been meaningless." That is the problem. Too many people have died, the years have been so hard that many Tamils want something to justify it all. And they trust Prabhakaran will get it for them. "Let us not forget that the problems did not start with the LTTE," says P. Sampanthan of the Tamil National Alliance, a moderate political group. "We talked to the government for the past 50 years to settle the Tamil question. Nothing happened until Prabhakaran brought in his invincible fighters." The ball is now in the government's court. Prabhakaran

has backed away from his demand for an independent homeland,

though he insists on genuine autonomy. Colombo has to decide

on how much will be tolerated by its majority electorate. "This

is like tightrope walking," explains Muthu, who lives in

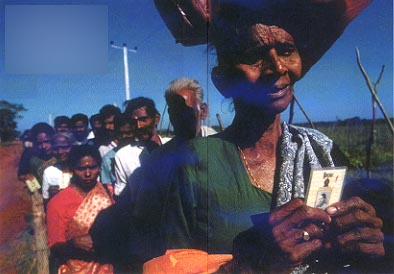

a If he had, Muthu might have been among the rebels and the soldiers late last week who started clearing mines on the A 9 highway that links northern Sri Lanka to the south. A battle for the road has claimed as many as 8,000 lives since 1997, including 3,000 Sri Lankan troops. Now, for the first time in six years, the enemies will share the road. Perhaps, laughed some soldiers, they will be putting those mines back in a few months. Or maybe, this time, peace will win and the road will lead to a brighter future. With reporting by Waruna Karunatilake/Colombo |