| CLASSIFICATION and TYPES of

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

| CLASSIFICATION and TYPES of

|

|

How would the mosque, the place of worship in Islam, be classified? Generally, architecture is classified according to: 1. material, 2. function, and 3. composition. Architecture has been always conditioned by materials produced in its locality. If a mosque is built of wood in a desert, the cost would be very high, due to transporting the material from far off places. The same can be said in the case of constructing a stone mosque in a land lacking quarries. People in every region have developed architecture by using materials easily available on location and pursuing their possibilities to their maximum.

EARTHEN MOSQUE : a mosque in Sirumu village, Mali

Earthen mosques are most frequently seen in Africa. People erect them of clay mixed with fibrous materials such as straw by hand or trowel, forming walls and pillars. If some timber is available, wooden roofs are made, if not, they would be arch structures.

BRICK MOSQUE : the Friday Mosque in Thatta, Pakistan

The Persian area, which does not produce stone of good quality, made bricks of burnt earth, and piled them up to erect mosques, fundamentally using arch and dome structures. Burnt bricks are much more accurate in construction and have a higher material strength than raw earth.

WOODEN MOSQUE : the Friday Mosque in Shrinagar, India

As opposed to desert regions, in mountain regions, though not so many in the sphere of Islam, where it rains throughout much of the year, trees grow and mosques are of wood. Kashmiris in the Himalayas used to construct mosques in the post-and-beam structure with cedars that grow extremely tall.

STONE MOSQUE : the Manutche Mosque in Ani, Turkey

Since a mosque is a ehouse of Godf, the use of permanent material such as stone, resistant against fire and rain, has been most desired; with the result most masterpieces came to be stone mosques.

In terms of 2. function, since Islam did not have a pyramidal church system, this is not a hierarchical classification but one based on the scale and purposes of worship practiced in situ: whether it is individual or collective, for funeral ceremonies or the two great yearly festivals. It has already been discussed.

In terms of 3. composition, this is a classification of eformsf of plans and spatial constitution. As we have already seen the difference between the esingle room-typef and ecourtyard-typef, we now pay attention to the four great typical mosque types. They are the eArabic typef, ePersian typef, eTurkish typef, and eIndian typef.

In response to the weakening of the Abbasid Dynasty, its subordinate local regions became politically independent and developed their own individual architectural cultures. Three empires especially, which were in a three-way contest over the entire Islamic world in early modern times (16th-17th centuries), respectively established characteristic mosque forms. That is, the Safavid Dynasty in Persia, the Ottoman Dynasty in Turkey and the Mughal Empire in India. Each empire constructed enormous mosques in their various territories and their influence spread even to its neighboring countries. Therefore, the Persian type, Turkish type and Indian type, along with the Arabic type, became typical mosque types. I will explain their traits in detail below.

A Chinese style mosque and an African style mosque

These are the most etypical formsf; other styles, such as Chinese style or African style, also exist, but are not called typical mosque types, because their countries did not form Islamic empires, having fewer influences, and are not considered as foremost mosque forms.

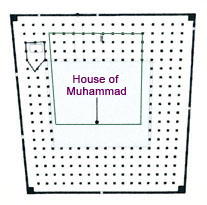

When the sixth Khalifa, Walid I, reconstructed the Prophetfs Mosque in Madina (Medina) in 705, the Great Mosques in Basra and Kufa had already been completed, so the Madina Mosque adopted almost the same plan. As Muhammadfs inclination must have reflected on these early mosques, it is assumed that he himself did not intend to make mosque architecture monumental.

Plans of the Prophetfs Mosque in Madina and Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo

Thus though the scale of mosques became larger, the mainstream was still pragmatic plain mosques. On the other hand, since Walid I was the Khalifa who constructed the first monumental mosque in Damascus (the Umayyad Mosque), he also embellished the interior of the Prophetfs Mosque in Madina with opulent mosaics.

As this courtyard-type mosques, modeled after the Prophetfs Mosque, were erected far and wide in the Arabic world, they are called eArabic typef mosques.

Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo and the Friday Mosque in Khiva

Incidentally, as opposed to wooden beams built horizontally over columns in four quarters, lined up arcades of brick or stone naturally generate a certain definite direction. In spite of the fact that whether the arcades are in a parallel direction or at right angles to the Qibla wall, each generating a different impression of emovementf in the interior space of a mosque, it is quite strange that Arabic type mosques have various directions without a fundamental principle.

As result, the other three Riwaq (cloisters) surrounding the Sahn (courtyard) has also either the same direction as the Haram (worship hall) or opposite. That might have related to the fact that they gradually became simple cloisters with a different character from the worship hall. The materials used in Arabic type mosques are either wood, brick or stone. While in a wooden mosque one can see far through slender timber columns, brick pillars are so thick that a multitude of them divides the interior space in pieces. This character generates a strange religious architectural space, which is quite different from that of modern architecture in which an extensive floor must be under a large spanned structure.

The Friday Mosque in Alger and Mezquita in Cordoba

The trait of Arabic type mosques, that everywhere from the courtyard to the Riwaq and Haram is thoroughly continuous, is best incarnated by the Amr Mosque in Old Cairo. It is the oldest mosque in Egypt, built in 641, and holds well the original structural system and spatial features, in spite of having been enlarged and reconstructed several times. In this mosque, since its columns are monolithic ones brought from ancient buildings, they do not especially disturb the visibility through its entire interior space, giving an impression as if the flowing colonnaded space spreads infinitely.

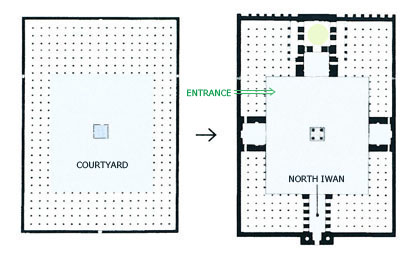

It was the introduction of eIwanf, an architectural legacy of the pre-Islamic Sassanid Dynasty, into the architectural composition of mosques by Persians that brought about an epochal development in the history of mosque architecture.

When the central axis was thus accentuated, a counterpart came to be desirable on the opposite spot of the courtyard on this axis. Setting up another iwan there opposite each other generated a eDouble-Iwanf mosque; a simple mosque of a hypostyle hall surrounding a courtyard thus grew into a highly modulated impressive building.

The Friday Mosque in Zavareh from the 12th century is said to be the first example of the Four-Iwan type. As it was a mosque in a local town, its scale is modest; its courtyard is about 16m square, with iwans of about a third of the width of each side facing each other, making the courtyard completely different from those of Arabic type mosques. The centripetalism of the courtyard surrounded by four iwans was so intense that the courtyard became a more symbolic space than the worship hall itself. In the case of the Friday Mosque of Isfahan, a classical hypostyle mosque (built in the Abbasid era) was dramatically altered into a Four-Iwan type mosque in the 12th century. The insides of the iwans formed half domes or semi-cylinder vault ceilings, often magnificently ornamented with Muqarnas> (stalactite decoration). It can be said that it was a manifestation of Persian peoplefs sensibility that attaches more importance to outer appearances than do the Arabs.

The schematic plans showing the development of the Friday Mosque of Isfahan.

There were also other changes from the Arabic to Persian types. The first was making roofs incombustible. In contrast to the roof of Arabic type mosques that was basically flat and made of timber in the wake of the Syria-Byzantine tradition, Persians sought a way of constructing buildings entirely with brick due to the lack of enough quantity of wood. They built an arch over every intercolumniation and a dome on each bay demarcated with four arches.

___ ___  The Bibi-Khanum Mosque in Samarkand, and Sultan Hassan Mosque in Cairo

This architectural form was applied not only to mosques but also to buildings serving other various functions, such as palaces, Madrasas (schools), Khanqahs (monasteries for Sufis), and Caravanserais. Madrasas especially came to profoundly connect with this form, using the half-exterior spaces of iwans as rooms for lectures or discussions.

What remains largely unsatisfied in the Persian Four-Iwan type mosques is the external relationship. Since this form fundamentally stuck to a concept concerned with the courtyard only, it was indifferent to the external appearance of mosques, and found no desirable system of approach from outside.

However, when this form was introduced into Central Asia, the iwan on the opposite of Macca transformed into the entrance and a larger iwan standing back to back is a Pishtaq, or monumental gateway.

Among the three empires that shared the Islamic world, the Ottoman Empire was the first established and the longest to survive (1299-1922). The Asian side of Turkey is currently called the Anatolian Peninsula or Asia Minor. In the 12th century it was ruled by the Seljuks of Rum, who constructed Seljuk-style buildings all over Anatolia under the strong influence of Syrian and Armenian architecture. In the Ottoman era, they were to develop an architecture of a quite different character from the Seljuks, putting greater emphasis on domes. What determined that direction was the Ottoman conquest of the capital of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople, in the middle of the 15th century.

The Hagia Sofia and Yeni Jamii in Istanbul, Turkey

This city, located at the point where Asia meets Europe, had long endured as an independent city even after most of its territories had been occupied by the Turks. It was the center of Eastern Christendom, holding the great church of Hagia Sophia, the magnum opus of Byzantine architecture, constructed in the 6th century. While deeply overwhelmed and influenced by it, Ottoman architects did their utmost to create mosques surpassing it in grandeur and beauty. As that was the process of accomplishment of Ottoman architecture, they developed the mosque type that was completely different from adjacent Persia. And even more differently to Arabic type hypostyle space, it developed dome architecture with an enormous astylar space. As they took root in western Anatolia, namely in the sphere of Byzantine culture, even before the conquest of Constantinople, the Ottomans had been evolving a mosque type based on the dome architecture of the Roman Empire influenced by Oriental architecture. That means Ottoman architecture was a relative of the great domed building, the Roman Pantheon.

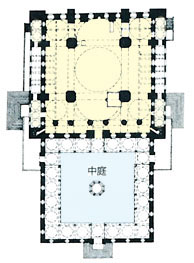

Plan of the Yeni Jamii in Istanbul, Turkey

There was also another cause for this Ottoman architectural evolution: in contrast to the Persian eFour-Iwan Typef in focusing courtyards rather than inner worship halls, the Turks, in a colder climate, attached more importance to worship halls isolated from outside air. They made even interiorized courtyards during the Seljuk age. Even though Persians made a domed space in front of the Mihrab, it was only a part of worship hall and its windows were small to avoid the heat, while the Turks covered up the entire worship hall with a huge dome with as many windows as possible to make the interior brighter in frequent dark cloudy weather in Istanbul. A Turkish enormous astylar interior space with omnipresent light embraces followers, as if it is space itself, or a manifestation of divine nature.

As for its exterior, since a Turkish type mosque usually stands on an orderly plan in the center of an extensive site, it has a much more formal external appearance than a Persian type one. However, its main dome does not look as great as its real height, because the closer one comes to a domed mosque, the more its highest part retreats and is lost from sight. Furthermore, their domes are always covered with blackish lead, thus often appearing gloomy to some degree.

The Suleymaniye (Mosque of Suleyman) in Istanbul, Turkey

As the Ottoman Empire subdued not only Turkey but also land from Egypt to Eastern Europe, it constructed Turkish type mosques, each consistng of a grayish dome and a pencil-type Minaret, throughout the territory. The magnum opuses are the Suleymaniye (mosque of Suleyman I) in Istanbul and the Selimiye (mosque of Selim II) in Edirne, both of which were designed by the greatest Ottoman architect, Mimar Sinan.

It was in the beginning of the 13th century that Islamic architecture started in India. As its propagation route was from Arabia to Persia, through Central Asia to India, Arabia was chronologically far from India. Nevertheless, since the prototype of mosques was the Arabic type, this type of mosque was also built in India. Naturally as the Persian type was also imported into India, the Iwan became a vocabulary of Indo-Islamic architecture, but the Four-Iwan type was eventually not established in this area. In the first place, courtyards were not part of the Indian tradition and were not suitable for the life and culture of India. Even if the Indian climate is tough, there is variety and richness of nature including dry and rainy seasons. It was not necessary to enclose and protect human territories with walls as in desert areas. The Indianfs temperament is to constantly express themselves outward. Making a centripetal and introvert world by surrounding a courtyard with four iwans was the opposite direction from Indian culture.

Asafi Mosque in Lucknow and Pearl Mosque in Delhi Fort, India

How about the Turkish type? In ancient India, wood was so abundant that the mainstream of building was wooden, having no familiarity wirth masonry arch and dome structures. Thatfs why in the Middle Ages, when wood became scarce, the Indians persisted in wooden-like framework construction in stone edifices, using stone as if it were timber. Technically, as the Indians could construct the enormous dome for the mausoleum Gol Gunbaz in Bijapur, larger than the Suleymaniye and Selimiye in Turkey, they had sufficient ability in terms of masonry construction. However, the point was aesthetic sense and mentality rather than technology. What the Indians always desired was esculptural architecturef, that is, formatively beautiful and fascinating when looked at from the outside, not setting up the great interior space or enclosed centripetal courtyard as main purposes.

The Arhai-Din-ka-Jhompra Mosque in Ajmer, India Since the Arabic type hypostyle hall was not contradictory to Indian framework architecture, the Indians erected Arabic type mosques, utilizing components of existing Hindu or Jain temples early on, and newly quarried stone later. However, these Arabian type mosques, which did not pay much attention to their external appearances, and having only hypostyle halls which surrounded a courtyard, did not fully satisfy the Indians' formative sense. Rather Persian style domes and Iwans must have looked more attractive, so most Indian mosques came to be symbolically crowned with a central dome and equipped with a Pishtaq, or monumental gate.

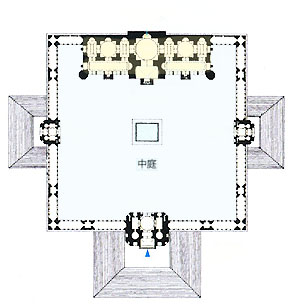

Plan of the Friday Mosque in Delhi, India

At the huge mosques constructed by the Mughals in early modern times, a courtyard was greatly enlarged like a square or plaza rather than an inner court. They are not Arabic type, in which hypostyle halls enclose a courtyard, nor Persian type, in which four Iwans surround it, but a sculptural edifice, the worship hall of which conspicuously protrudes into the courtyard from cloisters as if it were an independent building.

The Badshahi Mosque in Lahore, Pakistan

The Mughals placed a line of three domes over such sculptural independent-looking worship halls, finishing them with white marble and making them in a bulbous shape with swelled lower parts to achieve greater conspicuousness. Together with its central great Iwan and twin Minarets on both ends, and further decorations with Chatris on the roof, a majestic self-displaying sculptural architecture was accomplished. (On "Architecture of Islam" 2006) |