Chapter 1

Defining "Massacre"

Some refer to the hostilities that took place in Nanking in December 1937 and events that followed them as a massacre. Before we begin our examination of the "Nanking Massacre", we must first define the word massacre. Otherwise, we may repeat a mistake that others have made and view combatants who lost their lives as victims of a massacre. A major battle was fought in Nanking, and it claimed the lives of a large number of soldiers. The Battle of Iwo Jima, waged between Japanese and American forces, claimed many more lives (at least 27,000), but no one speaks of an "Iwo Jima Massacre".

Since international law does not define "massacre" per se, we shall construe the word as the unlawful, premeditated, methodical killing of large numbers of innocent people. We are saddened by the claims that Japanese military personnel were guilty of a massacre in Nanking, and that all who died during or as a result of the hostilities - be they soldiers who died in combat, stragglers killed during subsequent sweeps, or Chinese troops masquerading as civilians, who were apprehended and executed - were victims of a massacre. However, we are confident that anyone who reads this book will realize that nothing remotely resembling a massacre took place in Nanking.

At the IMTFE (International Military Tribune for the Far East, also known as the "Tokyo Trials"), the prosecution made various assertion as to the number of persons massacred in Nanking: 127,000, 200,000, and 100,000.9 In recent years, the original, postwar Chinese claim of 300,000 victims has escalated to 400,000.

Even among Japanese scholars, the number of "victims" varies considerably. Former Waseda University professor Hora Tomio, a historian and arguably the leading proponent of the "massacre" argument, believes there were 200,000 victims. Nihon University professor Hata Ikuhiko, who is viewed as a moderate in this controversy, has arrived at the figure of 40,000. Independent researchers Itakura Yoshiaki and Unemoto Masami, both of whom oppose the "massacre" theory, have posited 6,000-13,000 and 3,000-6,000, respectively. The bases for the various arguments (or the lack thereof) aside, the real problem that we face is the way in which persons who lost their lives during or after the conflict are classified: noncombatants, soldiers disguised as civilians, soldiers who surrenders, prisoners of war, and stragglers. Each category is different in nature. We believe that the following classification system used by Unemoto in Eyewitness Accounts of the Battle of Nanking is the most accurate.

Once the victims of the hostilities in Nanking have been properly classified, we discover that the majority of them died in combat or of combat-related causes. Far fewer deaths were the result of unlawful acts. It is true that Chinese soldiers who had surrendered were occasionally shot on the spot due to extenuating circumstances. And some civilians were killed accidentally during searchers for soldiers who had donned civilian clothing and infiltrated the Safety Zone. (The Nationalist military authorities must bear the responsibility for civilian deaths, since they tolerated the presence of armed Chinese combatants in the Safety Zone, in violation of international law.) However regrettable, tragedies like these were an inevitable byproduct of war.

No contemporaneous account refers to the mass murder of innocent civilians in Nanking. We will discuss this subject in greater depth later on in this book. But we wish to emphasize that the issue at hand is the number of deaths attributable to unlawful acts. It is our earnest hope that readers will be mindful of this distinction as they consider the arguments presented in this book.

Chapter 2

Population of Nanking in 1937

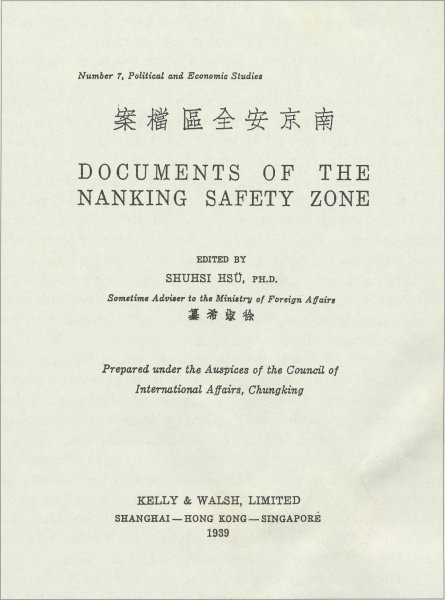

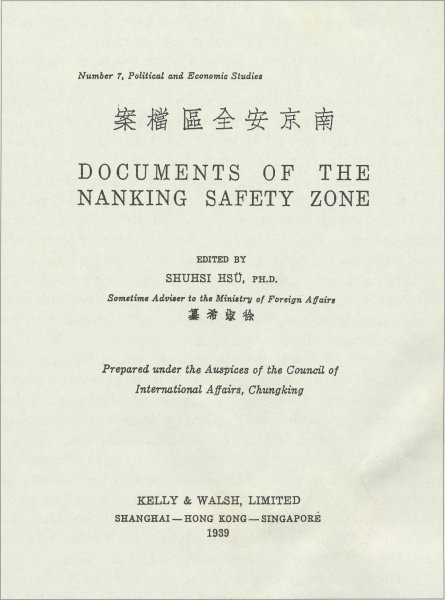

A 167-page book containing 69 missives issued by the International Commitee, and addressed to the Japanese, American, and German embassies. It is one of the most important contemporaneous sources on Nanking.

A 167-page book containing 69 missives issued by the International Commitee, and addressed to the Japanese, American, and German embassies. It is one of the most important contemporaneous sources on Nanking.

|

The first issue that must be addressed in any discussion of the Nanking Incident is: What was the population of Nanking when the Japanese attacked the city in December 1937?

On December 1, 1937, Ma Chaojun, the mayor of Nanking, ordered all residents to take refuge in a zone administered by the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone (referred to hereafter as the "International Committee"). After providing the Committee with a supply of rice and wheat, some currency, and a few police officers, Ma fled Nanking on the heels of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and other Nationalist leaders. By that time, Nanking's wealthy and middle-class residents, as well as the city's government officials, had already fled to the upper reaches of the Yangtze. The majority of those remaining in Nanking were poor people, who lacked the means to travel elsewhere.

At that time, Nanking was the capital of China. The word "capital" usually conjures up an image of a huge city, but Nanking is far smaller than Kyoto, Beijing, or Shanghai. According to a 1937 map, the city measured five kilometers from east to west. It was possible to walk from the largest gate, Zhongshan Gate, to Hanzhong Gate in about an hour. From Zhonghua Gate at the south end of the city, one could walk the 11 kilometers to Yijiang Gate, at the north end, in less than two-and-a-half hours. Nanking occupied an area of approximately 40 square kilometers (if one includes Xiaguan, which is outside the city limits), equivalent to 70% of Manhattan Island (57 square kilometers). Within its narrow confines were an airfield, low mountains, and farms.

The Safety Zone was established in a 3.8-square-kilometer area of Nanking, about the size of New York City's Central Park (3.4 square kilometers). It was administered by the members of the International Committee, all of whom were citizens of foreign nations. They gathered all the residents into the Safety Zone and endeavored to feed and house them. Between December 13 (the day the Japanese breached the gates of Nanking) and February 9, 1938, the International Committee issued 69 missives addressed and hand-delivered to the Japanese, American, British, and German embassies, on an almost daily basis. Most of them are complaints about misconduct on the part of Japanese military personnel, or pleas to military authorities to improve public safety or supply food to the refugees. These 69 documents are contemporaneous records, and should certainly be considered primary sourced. Unfortunately, the Japanese Foreign Ministry burned them toward the end of World War II, so the Embassy's copies are no longer extant. But they were compiled by Dr. Hsu Shuhsi, a professor at Beijing University, under the title Documents of the Nanking Safety Zone. Many of them also appear in What War Means,10 edited by Manchester Guardian correspondent Harold Timperley, and were submitted as evidence to the IMTFE. As shown in the photograph on p.11, the version edited by Hsu Shuhsi bears the imprimatur of the Nationalist government: "Prepared under the auspices of the Council of International Affairs, Chunking". It was published by the Shanghai firm Kelly & Walsh in 1939. Any discourse on the Nanking Incident that disregards these valuable resources is suspect.

There are four references to the population of Nanking in late 1937 in Documents of the Nanking Safety Zone; all of them state that the total refugee population was 200,000.11 A report written by James Espy, vice-consul at the American Embassy, and dispatched to the United States, and another report written by John Rabe, chairman of the International Committee, also mention that Nanking's population was 200,000.

However, Frankfurter Zeitung correspondent Lily Abegg, who escaped from Nanking immediately before the city fell, wrote the following in an article dispatched from Hankou.

Last week about 200,000 people left Nanking. One million souls once inhabited the city, but their numbers had dwindled to 350,000. Now there are at most 150,000 people remaining, but waves of evacuees seem interminable.12

Maj. Zhang Qunsi, who was taken prisoner by the Japanese, revealed that there were 50,000 Nanking Defense Corps soldiers and 100,000 noncombatants in the city. Another prisoner, Maj.-Gen. Liu Qixiong, who was later appointed head of the Nanking Military Academy (during Wang Jingwei's administration), and who commanded the brigate that defended the Yuhuatai position, estimated the population of Nanking as "approximately 200,000". In an entry in his war journal dated December 20, Gen. Matsui Iwane, commander-in-chief of the Shanghai Expeditionary Force wrote, "There are 120,000 Chinese in the Refugee Zone, most of them poor people".13

Taking all these sources into account, we can state with certainty that the population of Nanking at the end of 1937 was somewhere between 120,000 and 200,000. We know from contemporaneous records that the members of the Nanking Defense Corps, under the command of Tang Shengzhi, numbered between 35,000 and 50,000. Even allowing for gross underestimates, the population of Nanking could not have been less than 160,000 or more than 250,000. And even if the Japanese had murdered every single member of the Nanking Defense Corps and every single civilian, they could not have killed more than 160,000-250,000 Chinese. To massacre 300,000 persons, they would have had to kill many of them twice.

When confronted with these figures, proponents of the massacre theory attempt to enlarge the civilian population of Nanking. For instance, Hora Tomio writes:

When the Japanese military commenced its attack on Nanking, there were reportedly between 250,000 and 300,000 residents remaining in the city.

Reports have it that after stragglers were eliminated during the sweep, there were nearly 200,000 persons residing in Nanking.

Therefore, by the process of subtraction, we arrive at a total of 50,000-100,000 massacre victims.14 [Italics supplied]

His repeated use of phrasing like "reportedly" and "reports have it" implies that his sources are, at best, rumors. Rumors do not constitute proof. Hora is simply allowing his imagination to run away with itself, or guessing. None of his claims is the least bit reliable.

Like Hora, the authors of Testimonies: The Great Nanking Massacre have inflated the population of Nanking to support their accusation that 300,000-400,000 persons were massacred.

According to our research, the population of the Safety Zone, at its highest, was 290,000. When the massacre was nearing an end, and the enemy was forcing the refugees to leave the Safety Zone, it claimed that the population was 250,000. Therefore, the population had decreased by 40,000 in less than two months. There were many reasons for that decrease, but the primary reason was, without a doubt, the enemy's massacre of huge numbers of refugees.15

How did the authors arrive at the figure of 290,000? Like Hora, they present no proof. Iris Chang has inflated the population even further.

If half of the population of Nanking fled into the Safety Zone during the worst of the massacre, then the other half -- almost everyone who did not make it to the zone -- probably died at the hands of the Japanese.16

In a letter to the Japanese Embassy dated December 17, 1937, John Rabe, chairman of the International Committee, wrote: "On the 13th when your troops entered the city, we had nearly all the civilian population gathered in a Zone".17 Chang either disregarded this document or failed to consult it. Whatever the case, she has invented a group of people residing outside the Safety Zone, and numbering 200,000-300,000.

At the IMTFE, defense attorney Levin broached a question that pierced the heart of this problem.

Mr. Brooks calls my attention to the fact that in another portion of the affidavit is contained the statement that 300,000 were killed in Nanking, and as I understand it the total population of Nanking in only 200,000.

Flustered, William Webb, the presiding justice, replied, "Well, you may have evidence of that, but you cannot get it in at this stage", thus suppressing any further discussion of the matter.18

Therefore, the question of the actual population of Nanking was never addressed at the IMTFE, and a most bizarre judgements was handed down, in which the (unsubstantiated) number of massacre victims was stated variously as 100,000, 200,000, 127,000, etc. Since then, proponents of the massacre have avoided the population issue, resorted to guesswork (Hora), or invented their own statistics, as Iris Chang did.

Chapter 3

Nanking's Population Swells as Residents Return

A decline in the population of Nanking following the hostilities would lend support to assertions that Japanese troops perpetrated a massacre there. However, the population did not decline -- swelled.

We refer readers to the table accompanying this chapter, which we have compiled from population statistics appearing in Documents of the Nanking Safety Zone and in the diaries of John Rabe, chairman of the International Committee. Documents of the Nanking Safety Zone is a primary source consisting of 69 missives sent by the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone and, therefore, its members required an accurate grasp of the population.

Documents dated December 17, 18, 21, and 27 state that there were 200,000 refugees in Nanking. However, by January 14, the population had burgeoned to 250,000, where it remained until the end of February. Most of the increase can be accounted for by returning residents, who had fled to outlying areas to escape the war.

When the word spread that order had been restored to Nanking, streams of people entered the city and began preparations for the New Year holiday. According to the prosecution's general summation at the IMTFE, "Once the Japanese soldiers had obtained complete command of the city, an orgy of rape, murder, torture and pillage broke out and continued for six weeks".19 This was an outright lie. Who would be foolish enough to return to a city where a massacre and unspeakable atrocities were taking place?

From late December through early January, Japanese troops issued 160,000 civilian passports to refugees in Safety Zone during their attempts to ferret out Chinese soldiers masquerading as civilians. However, no passports were given to children under 10 or to the elderly (those aged 60 years and over). In a letter to Committee Chairman John Rabe wrote:

We understand that you registered 160,000 people without including children under 10 years of age, and in some sections without including older women. Therefore there are probably 250,000 to 300,000 civilians in the city.20

At the end of March 1938, Lewis Smythe conducted his own census, hiring students to do the fieldwork. In a report entitled War Damage in the Nanking Area, he writes:

We venture an estimate of 250,000 to 270,000 in late March, some of whom were inaccessible to the investigators, and some of whom were passed by; 221,000 are represented in the survey.21

Later on in the same document, Smythe refers to the population as of late May.

On May 31, the residents gathered in the five district offices of the municipal government (including Hsiakwan [Xiaguan], but apparently no other actions outside the gates) numbered 277,000.22

He also mentions that "a noticeable inflow from less orderly areas near the city probably built up a small surplus over departures ...".23

The population increase alone is proof that peace had been restored to Nanking.

In his war journal, Gen. Matsui wrote, "Residents seem to be returning gradually".24 But according to Chinese accounts, some of them presented at the IMFTE, the "massacre" reached its peak precisely one week after the Japanese occupation, when bands of Japanese soldiers shot every Chinese who crossed their paths, raped every woman they encountered, looted, and burned. Corpses were everywhere, mountains of them. Rivers of blood ran down the streets. If those accounts are accurate, why did so many residents return to a city that had been transformed to a hell on earth?

In an interview, Nishizaka Ataru, a former member of the 36th Infantry Regiment(the first unit to enter Nanking through Guanghua Gate), told this winter that his unit was ordered to march to Shanghai. While traveling east on Jurong Road on December 23, Nishioka encountered many groups of refugees on their way back to Nanking.

The December 20, 1938 morning edition of the Asahi Shinbun devoted a half-page to a collection of photographs entitled "Peace Returns to Nanking", one of which was taken on December 18. Captioned "A group of returning refugees escorted by the Imperial Army", it shows a group of 200-300 refugees lined up waiting to reenter Nanking. Would they have been so anxious to return during, or even after, a massacre?

Population Shifts in the Nanking Safety Zone

Chapter 4

"Mountains of Dead Bodies" That No One Saw

When he took the witness stand at the IMTFE, Red Swastika Society Vice-Chairman Xu Chuanyin testified as follows.

The Japanese soldiers, when they entered the city -- they were very very rough, and they were very barbarious: They shoot at everyone in sight. Anybody who runs away, or on the street, or hanging around somewhere, or peeking through the door, they shoot them -- instant death.

I saw the dead bodies lying everywhere, and some of the bodies are very badly mutilated. Some of dead bodies are lying there as they were, shot or killed, some kneeling, some bending, some on their sides, and some just with their legs and arms wide open. It shows that these been done by the Japanese, and I saw several Japanese were doing that at that very moment.

One main street I even started try to count the number of corpses lying on both sides of the street, and I started to counting more than five hundred myself. I say it was no use counting them; I can never do that.25

Jinling University Professor Miner Searle Bates, an American, also testified at the IMTFE.

The bodies of civilians lay on the streets and alleys in the vicinity of my own house for many days after the Japanese entry.

Professor Smythe and I concluded, as a result of our investigations and observations and checking of burials, that twelve thousand civilians, men, women and children, were killed inside the walls within our own sure knowledge.26

Witness after witness described gruesome sights that they had seen in Nanking. There were "mountains of dead bodies" inside the city walls. Corpses filled out only Nanking's main roads, but also its lanes and alleys. "Knee-high rivers of blood flowed down the city's streets". "Bodies were piled up on the streets, and automobiles drove over them". The Japanese shrank in horror as they listened to and read about these ghastly testimonies for days on end. Every evening NHK Radio broadcast a program entitled "This is the Truth", which recounted inhumane, barbaric acts perpetrated by Japanese military personnel in the most lurid, sensational manner. Japan's newspapers emulated this style in their coverage. But not one of the tens of thousands of soldiers and some 150 newspaper correspondents and photographers who followed them into Nanking ever saw anything on the sort.

On December 15, 1937, two days after the Japanese occupied Nanking, Tokyo Nichinichi Shinbun corresponds Wakaume and Murakami interviewed Bates at his home on the Jinling University campus. The professor greeted his two visitors jovially, shook hands with them, and told them that he was grateful to Japanese troops for their orderly entry into Nanking, and for having restored peace so expeditiously.27 Why Bates later made an about-face and testified that "the bodies of civilians lay on the streets and alleys in the vicinity of my own house for many days after the Japanese entry" and that "twelve thousand civilians, men, women and children, were killed inside the walls" at the IMTFE we will never know. The reports Wakaume and Murakami dispatched to Japan mentioned nothing resembling Bates' testimony. If, as Bates asserted, there were indeed 12,000 corpses strewn about a city the size of Manhattan Island, they would have filled every street, lane, and alley. The stench of decomposing bodies, which can be detected within 100 meters, would have permeated their clothing and lingered through several launderings. Even when the corpses had been removed, the foul odor would have persisted for three or four days.

Sakamoto Chikashi, commander of the 2nd Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment (from Miyakonojo, Miyazaki Prefecture), vividly recalls the situation in Nanking in December 1937.

At about 8:00 a.m. on December 13, we commenced our operation. Having climbed over a section of a wall that had been breached, we assembled near the southwest corner of the city by about 10:30 a.m. ... The main strength of the Regiment advanced, moving alone the city walls, looking for Chinese stragglers. My battalion headed north toward the eastern sector of Nanking. At about noon, I noticed a restaurant on the left side of the road. It was open for business, and we saw a man who appeared to be the owner inside. Accompanied by some of my men, I went in. We enjoyed our first decent meal in a long time. The owner was delighted when we paid him with silver coins.

After resting for a bit, we marched on. At about 2:30 p.m., we arrived at Qingliangshan [also known as Wutaishan], where we confiscated six heavy guns. We received orders to halt our advance, and bivouacked in the vicinity that night.

We didn't inspect every single home, but other than the restaurant owner, we saw no civilians, no enemy soldiers, no dead bodies. Nor did we hear any significant gunfire.

According to an article in the Asahi Shinbun, in Travels in China, Honda Katsuichi wrote that more than 20,000 Chinese were massacred at Wutaishan. However, as I mentioned earlier, all we did there was confiscate six guns. The same article also states that on December 13, Japanese troops blockaded the road to Xiaguan by closing Yijiang Gate, and shot a large number of fleeing civilians to death. At that time, we were in Qingliangshan. From there to Yijiang Gate, the distance is four or five kilometers as the crow flies. If something like that had happened, we would surely have the machine gun fire.

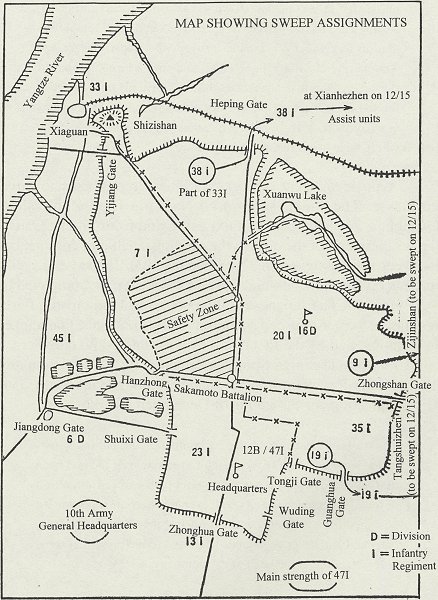

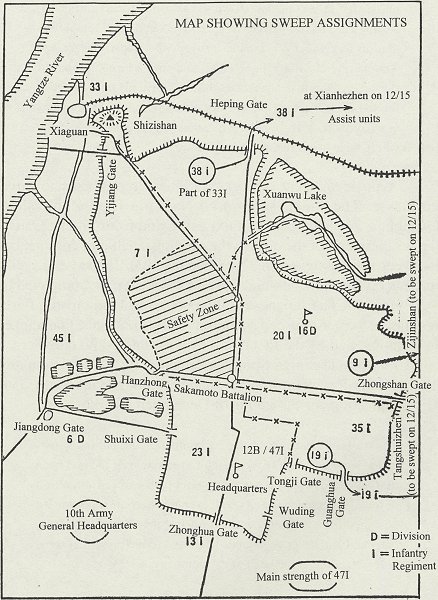

At daybreak in December 13, Chinese troops began to retreat en masse. The Japanese entered Nanking from Zhongshan, Guanghua, Zhonghua, and shuixi gates, and from Yijiang Gate at the northern end of the city. In the evening, each unit commenced its sweep of an assigned area (see map in p.23). The sweep reached its peak on December 15 and was, for the most part, completed by December 15. The Japanese soldiers, who had anticipated fierce resistance, were astonished and unsettled by the silence that reigned in Nanking, and by the fact that encountered no one there.

First Lt. Tsuchiya Shoji, commander of the 4th Company, 19th Infantry Regiment, entered Nanking through Guanghua Gate. His recollections of the events of December 13 follow.

The walls had been destroyed by bombardment, but the homes inside were completely intact. Not even one roof tile had been displaced. However, an atmosphere of eerie silence and desolation pervaded the city, and even my stalwart subordinates hesitated for a moment. In the midst of this ineffable silence, one that I had never experienced before, I found myself, at some point, standing at the head of my company.

As we proceeded further into the city, I sensed that Nanking was truly deserted. No enemy bullets flew at us. We saw no one -- only endless, silent rows of houses. After we had advanced several kilometers (I don't remember how many) we came upon a huge, reinforced concrete building. We were not at all prepared for what we saw there.

When we entered what seemed to be an auditorium, we saw many nurses tending to seriously wounded Chinese soldiers who couldn't be evacuated. The nurses just stood there and stare at us. I bowed to them, and left the building. We had resigned ourselves to a battled, but not a drop of blood was shed that day.29

Note that all these witnesses agree that Nanking was "eerily silent", orderly, and completely deserted.

The following is an excerpt from an interview this writer conducted with Tanida Isamu, former 10th Army staff officer.

On the morning of December 14, Headquarters personnel entered Nanking. In the afternoon, we established a base in a bank building near Nanking Road. By that time, the city was already quiet. During the whole time I was stationed there, I heard no gunfire whatever. That same day, I made a tour of Nanking, and took photographs. I did see some corpses, but only a few. The city was peaceful.

As he spoke, Tanida showed me the photographs he had taken. He told me that he saw approximately 1,000 bodies at the wharf in Xiaguan, which he believed to be those of Chinese soldiers killed in action on December 13. I was amazed at the details he remembered. He also mentioned that December 14 is his birthday, and how pleased he was to have the opportunity to celebrate it in the company of Lt.-Gen. Yanagawa Heisuke, commander-in-chief of the 10th Army, and how they toasted each other with cold sake.

In The Battle of Nanking, Vol.6,30 former Asahi Shinbun correspondent Kondo states that "there were corpses of both Chinese and Japanese military personnel outside Guanghua Gate, the result of the bloody battled fought there. But I don't recall there being a lot of them. I saw no dead civilians". Also, Futamura Jiro, a photographer who worked for Hochi Shinbun and later Mainichi Shinbun, states, "Together with the 47th Infantry Regiment, I climbed over the wall into the city, but I saw very few corpses there".

We could cite any number of similar testimonies, but we believe that we have proved our point. No one saw "mountains of dead bodies" or "rivers of blood". No member of the Japanese military, no Japanese newspaper reporter, none of the 15 members of the International Committee, none of the five foreign reporters on assignment in Nanking, no foreign national saw scenes remotely resembling those described by Chinese witnesses who testified at the IMTFE.

Chapter 5

International Committee's Statistics on Crimes Attributed to Japanese Military Personnel

Among the 69 documents included in Documents of the Nanking Safety Zone, which describes the situation in Nanking following the Japanese occupation of that city, are reports of crimes allegedly committed by Japanese military personnel between December 13, 1937 and February 9, 1938. Any examination of these cases must be preceded by an awareness of the following facts.

-

All 15 members of the International Committee, which issued the reports, were foreign nationals (seven Americans, four Englishmen, three Germans, and one Dane). At the time, the nations they represented were, for all intents and purposes, Japan's enemies, in that they resented and opposed Japanese encroachments on Chinese territory and supported the Chinese military, both materially and spiritually. John Rabe, the Committee's chairman, was a citizen of Germany, a nation that was not friendly toward Japan, the popular perception not withstanding. The German government supported the Chinese Nationalists, and supplied a team of military advisors headed by Gen. Alexander von Falkenhausen, which trained the Chinese Army. Rabe was president of Siemens' Far Eastern operations. During his assignment in China, he sold massive amounts of German-made weaponry to the Nationalist government.

-

Most of the crime reports prepared by Committee members were based on hearsay or rumors (see table at the end of this chapter).

-

The Committee monitored crimes committed by Japanese troops both in the Safety Zone and in other parts of Nanking.

-

Serving as the Committee's informants were the Red Swastika Society, the YMCA, and a spy network of Chinese youths, a special detachment of the Nationalist government's Anti-Japanese Propaganda Bureau.31

As soon as the International Committee received information from these spy networks at its office at 5 Ninghai Road, one of its members would type up a report, which was then hand-delivered to the Japanese Embassy or other foreign legations. These reports were issued on a daily basis (in some cases, twice daily). In addition to letters accusing Japanese soldiers of crimes, the Japanese Embassy received requests for food and improved public safety. Additionally, as an information center where spies were received and as a conference site where demands and reports of Japanese crimes -- they simply accepted all of them as fact and recorded them.

The Committee's liaison at the Japanese Embassy was Fukuda Tokuyasu. At the time, Fukuda was a junior foreign service officer. After his return to Japan, he was appointed private secretary to Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru. He then embarked on a political career, serving first in Japan's Diet, and later as defense minister, director-general of the Administrative Management Agency, and them as posts and telecommunications minister. A gifted politician, Fukuda earned the respect and admiration of his compatriots. He was also a close fiend of this writer, with whom he shared recollections of his service in Nanking.

My duties included visiting the office of the International Committee, an organization formed by foreign nationals, nearly every day. There was much coming and going of Chinese youths, who were reporting incidents. Usually, what they had to say was something like the following: "Japanese soldiers are gang-raping 15 or 16 girls on X street right now" or "A band of Japanese soldiers has broken into a house on Taiping Street, and is now burglarizing it". Whichever Committee member or members was available (Rev. Magee, and Mr. Fitch, for instance) would proceed to type up the reports right in front of my eyes.

I voiced my objections to these reports any number of times: "Just a moment -- you can't submit a protest without verifying this incident". Sometimes I would insist that Committee members accompany me to the site where the rape or looting had supposedly taken place. When we arrived there, we never found evidence of a crime's having been committed. None of these places was even occupied.

One morning, the embassy received a complaint from the American vice-consul: He had been told Japanese soldiers were stealing lumber from an American-owned warehouse in Xiaguan and loading it onto a truck. I was ordered to go to Xiaguan immediately and stop them. I telephoned Headquarters and asked Staff Officer Hongo Tadao to accompany me there. Together with the vice-consul, we rushed to Xiagaun in the middle of a snowstorm. It must have been about 9:00 in the morning. When we arrived, there wasn't a soul there. The warehouse was locked. Nothing had been stolen. I scolded the vice-consul for making such a fuss over nothing. We received false alarm that almost every day.

I am convinced that most of the reports that appear in Timperley's Japanese Terror in China32 were typed by Fitch or Magee and sent to Shanghai without anyone's having inspected the alleged crime scene.

In the 69 letters written by the International Committee are accounts of 444 crimes allegedly perpetrated by Japanese military personnel. Accounts of only 398 cases were published in Documents of the Nanking Safety Zone, most likely because Committee members had decided that the remaining 46 cases were particularly unconvincing.

In Nanking, Fukuda examined protests issued by Chinese most of them were completely without merit. Nevertheless, the stream of protests from the International Committee against Japanese acts of violence alarmed the East Asian Bureau of the Foreign Ministry. Ishii Itaro, then head of the Bureau, describes the reaction at the Ministry in his memoirs. The following excerpt is from a diary entry dated January 6, 1938.

We received letters from Shanghai detailing unspeakable acts of violence, including looting and rapes, committed in Nanking by our soldiers. The perpetrators of these crimes have disgraced the Imperial Army and betrayed the Japanese people. This is a matter with grave social implications. ... How could men fighting in the name of our Emperor behave in such a way? From that time on, I referred to those incidents as the "Nanking atrocities".33

Japanese proponents of the massacre argument make liberal use of this passage, but they do so without a proper understanding of Ishii's reasons for believing the unfounded protests or of this animosity toward the military. At a liaison conference held at the Headquarters of the General Staff in Tokyo on December 14, 1938 (one day after the occupation of Nanking), an angry Ishii lashed our at military officials.

At this point, who cares about the proposal [outlining conditions for peace]? Japan should go as far as it can go. When it reaches an impasse, it will be forced to see the light.34

I experienced a perverse pleasure upon uttering those rebellious words.35

The "Nanking atrocities" had provided Ishii with the perfect opportunity to strike back at military authorities. His hatred of them may have stemmed from personal feelings of hostility toward his own nation. For instance, he mentions relations between Japan and China in his memories, he writes "China" first, contrary to the conventional method, an indication that his sympathies lay with China. Furthermore, when he was decorated by the Emperor, he wrote that he "wasn't at all pleased".36 However, when he received a similar award from China, he expressed delight at having been so honored.37 We find it ironic that a person harboring such sentiments was chief of the Foreign Ministry's East Asian Bureau.

We have digressed a bit, but we felt it was important to include this information, since Hitotsubashi University professor Fujiwara Akira, in his recent book,38 cites Ishii's memoirs as irrefutable proof that a massacre was perpetrated in Nanking.

As Fukuda Tokuyasu has revealed, though the majority of the 398 "cases of disorder by Japanese soldiers in the Safety Zone" protested by the International Committee had no basis in fact, every one of them was accepted. Tomizawa Shigenobu, an independent researcher, has made a computer analysis of these cases, which appears in table form at the end of this chapter.

There were 516 cases in all, not 398, since some of them include accounts of two incidents. Among them are 27 murder cases (54 victims). In only two cases are the names of the victims specified, and there were eyewitnesses to only one case. Two hundred thousand people were crowded into the Safety Zone, which encompassed an area the size of New York's Central Park but, incredibly, only one murder caught the attention of the Zone's residents. Since the International Committee accepted any and all rumors, 27 murder cases were recorded and protested, despite the absence of specifics or witnesses. Where did a massacre of any extent take place?

Thus were the accounts of all acts of misconduct occurring between December 13, 1937 and February 9, 1938, for which Japanese military personnel were allegedly responsible, documented by the International Committee, all of whose members harbored malice toward Japan.

STATISTICAL SUMMARY OF INCIDENTS REPORTED IN DOCUMENTS OF THE NANKING SAFETRY ZONE

Chapter 6

Japanese Quickly Restore Order in the Safety Zone

A. No Women or Children Killed by the Japanese

All of Nanking's civilian residents, including women and children, had taken refuge in the Safety Zone, which was administered by the International Committee.

The Japanese occupied Nanking on December 13. The 7th Infantry Regiment from Kanazawa, commanded by Col. Isa Kazuo, was entrusted with the sweep of the Safety Zone. On December 14, Col. Isa stationed setries at 10 locations near the entrances and exits of the Safety Zone, ordering them to prevent anyone from entering or leaving the Zone without good reason. At the Tokyo Trials, Col. Wakizaka Jiro, commander of the 36th Infantry Regiment, testified that when he attemted to enter the Safety Zone, a sentry refused to allow him to pass.40 The fact that even a high-ranking officer was denied entry is evidence of how meticulously orders were followed.

As a result of strict orders issued by Commander-in-Chief Matsui, not one shell was fired into the Safety Zone, nor were aerial bombs dropped on it. No acts of arson were committed -- in fact, there were no fires in the Zone. The Safety Zone was, as its name implies, safe. Rapes, assaults, and other crimes committed by a few renegade Japanese soldiers are described in records kept by the International Committee.41 But no women or children were murdered, nor were any such crimes even documented. Furthermore, burial records prepared by the Red Swastika Society list virtually no women or children. It is possible that a few civilians were dtafted to serve as laborers, or mistakenly apprehended during the hunt for Chinese military personnel masquerading as civilians. However, contemporaneous records describe the Safety Zone as, for the most part, a peaceful and quiet place. Consequently, every resident of Nanking was safe since, with a few exceptions, all civilians had congregated there.42

John H.D. Rabe, chairman of the International Committee, sent a letter to the Japanese military authorities on behalf of the entire Committee, which reads in part:

We come to thank you for the fine way your artillery spared the Safety Zone and to establish contact with you for future plans for care of Chinese civilians in the Zone.43

The following are excerpts from a diary and notes kept by Dr. James McCallum, a physician assciated with the Jinling University Hospital, which were read at the Tokyo Trials by Ito Kiyoshi (Gen. Matsui Iwane's attorney) during the presentation of Matsui's defense. They describe acts of kindness performed by Japanese soldiers.

We have had some very pleasant Japanese who have treated us with courtesy and respect (December 29, 1937).

Occasionally have I seen a Japanese helping some Chinese, or picking up a Chinese baby to play with it (December 29, 1937).

Today I saw crowds of people flocking across Chung Shan [Zhongshan] Road out of the Zone. They came back later carrying rice which was being distributed by the Japanese from the Executive Yuan Examination Yuan (December 31, 1937).

Succeeded in getting half of the hospital staff registered today. I must report a good deed done by some Japanese. Recently several very nice Japanese have visited the hospital. We told them of our lack of food supplies for the patients. Today they brought in 100 shing [jin (equivalent to six kilograms)] of beans along with some beef. We have had no meat at the hospital for a month and these gifts were mighty welcome. They asked what else we would like to have (December 31, 1937).44

In War Damage in the Nanking Area, Lewis Smythe wrote:

The fact that practically no burning occurred within the zone was a furhter advantage.45

The late Maeda Yuji, former correspondent for Domei Tsushin46 and former director of the Japan Press Center, described his experiences in Nanking in Sekai to Nippon.

Those who claim that a massacre took place in Nanking, leaving aside their accusations that 200,000-300,000 persons were murdered for the moment, assert that most of the victims were women and children. However, these supposed victims were, without exception, in the Safety Zone and protected by the Japanese Security Headquarters. The Nanking Bureau of my former employer, Domei Tsushin, was situated inside the Safety Zone. Four days after the occupation, all of us moved to the Bureau, which served both as our lodgings and workplace. Shops had already reopened, and life had returned to normal. We were privy to anything and everything that happened in the Safety Zone. No massacre claiming tens of thousands, or thousands, or even hundreds of victims could have taken place there without our knowing about it, so I can state with certitude that none occurred.

Prisoner of war were excuted, some perhaps cruelly, but those executiona were acts of war and must be judged from that perspective. There were no mass murders of noncombatants. I can not remain silent when an event that never occurred is perceived as fact and described as such in our textbooks. Why was historical fact so horribly distorted? I believe that the answer to this question can be found in the postwar historical view, for which the Tokyo Trials are responsible.47

Accounts of the Nanking Incident in Japanese textbooks contain wording similar to the following: "Japanese military personnel killed 70,000-90,000 persons, if one counts only civilians, including women and children" (Tokyo Shoseki) and "Japanese soldiers murdered vast numbers of civilians, including women and children" (Kyoiku Shuppan). Every history textbook mentions that women and children were murdered in Nanking, but what is the basis for these claims? Even citizens of other nations that were antagonistic to Japan expressed gratitude to Japanese soldiers for maintaining order in the Safety Zone and for acts of kindness. This writer is unable to understand why Japanese textbooks contain accounts that distort the facts, and encourage our children to despise their motherland and their forebears.

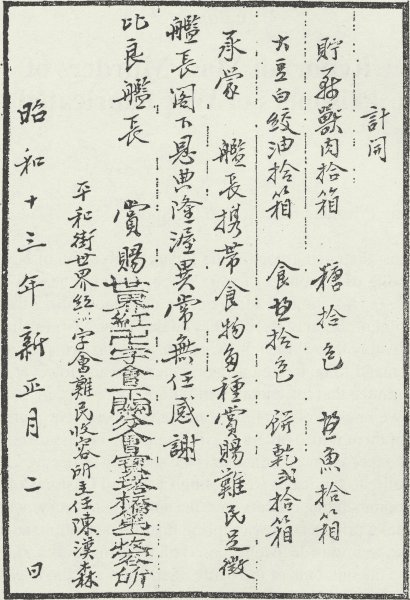

B. A Letter of Gratitude From Another Refugee Zone

At this time, we would like to mention another refugee zone. About 1.8 kilometers north of Xiaguan, where bloody battles that claimed thousands of lives were fought, is the town of Baotaqiao. Over 6,000 refugees had congregated on the grounds of Baoguosi, a temple located in that town. The 11th Squadron, led by the flagship Ataka (commanded by Maj.-Gen. Kondo Eijiro), was sailing down the Yangtze on December 13. The fleet encountered heavy fire from a Chinese position at Liuzuzhang, but finally broke through the blockade and headed toward Xiaguan. Hozu and Seta made up the advance guard, followed by Kawakaze, Hira, Ataka and other warship. The Yangtze and its banks were crowded with boats and rafts carrying fleeing enemy soldiers, which the Japanese warship attacked. On December 14, the gunboat Hira anchored at Zhongxing wharf, one nautical mile downstream from Xiaguan. Her commander, Lt.-Col. Doi Shinji, decided to reconnoiter Baotaqiao. A munitions depot was located there, as well as a railroad siding, weapons, provisions, uniforms and other military supplies. Treches had been dug all around the town, from which stragglers would often emerge, terrorizing the residents. Baotaqiao had become an extremely dagerous, lawless place. Lt.-Col. Doi voluntarily took on the responsibility of restoring peace and stability to Baotaqiao and its outskirts, whose 20,000 residents and several thousand refugees were living in fear.

First, Doi repaired the bridge to Xiaguan. Then he set about distributing food, clothing, and other necessities to the beleaguered residents. He changed the name of the town to "Pinghejie" (Town of Peace) and, with his men, protected the townspeople from marauding Chinese stragglers. Thanks to his efforts, order was quickly restored, but the most urgent problem, the lack of food, remained unsolved.

At the end of the year, the lead ship in a minesweeping operation struck a mine at the Wulongshan Fort blockade and sank. Doi, ordered to participate in the rescue effort, boarded the Hira and sped to the disaster site. When the rescue work had been completed, the Hira sailed to Shanghai, carrying a large number of dead and wounded sailors.

Lt.-Col. Doi visited Fleet Headquarters on the Izumo, then at anchor in shanghai, and described the desperate situation in Pinghejie. Headquarters staff, moved by Doi's earnestness and sincerity, granted his petition for relief provisions. Food for the refugees was loaded onto the Hira and transported to the Zhongxing wharf. The ship arrived on New Year's Day in 1938. Chen Hansen, chairman of the local branch of the Red Swastika Society, a charitable organization, accepted the provisions, described below, on behalf of the refugees.

-

10 crates of preserved beef and pork

10 large bags of refined sugar

10 crates of dried fish

10 crated of soybean oil

10 packages of table salt

20 crates of dried rice cakes

To welcome the Hira, the refugees set off firecrackers. Each house sported a Japanese flag, and a banner reading "Pinghejie, Xiaguan, Nanking" was displayed at the town's entrance. The refugees ang townpeople cheered when the ship arrived. A joyful mood prevailed.

On the following day, the town's officials put on their best clothes and lined up at Baguo Temple to receive Lt.-Col. Doi and his crew. Chen Hansen presented them with a receipt and a letter of gratitude (see illustration in P.41).

C. Funeral Services for Fallen Enemy Soldiers

On the night of December 13, the Wakizaka Unit (36th Infantry Regiment), the first to enter Nanking, cremated the remains of Japanese soldiers killed in action. Its members then erected a tall wooden tablet with a prayer inscribed on it in honor of the enemy dead, at which they offered flowers and incense. They buried the Chinese soldiers with respect, and chanted sutras for the repose of their souls all through the night.

The point we wish to make here is that there was nothing remarkable about the good deeds performed by Lt.-Col. Doi or Col. Wakizaka. They were simply demonstrating compassion, which was an integral aspect of bushido, the traditional code of conduct of the Japanese warrier. In fact, Staff Officer Yoshikawa Takeshi was severely reprimanded by Gen. Matsui, who claimed that the Chinese war dead were not handled with sufficient care. Could soldiers and commanders of this caliber have participated in or even condoned the indiscriminate killing of innocent women and children?

The Chinese have claimed that several tens of thousands of persons were massacred at Meitan Harbor and on the property of the Heji Company. However, Commander Doi steadfastly denies such claim, having never heard even rumors of such slaughter. From his testimony alone, readers should realize that this claim was preposterous propaganda.

The most disputed aspect of the Japanese invasion of Nanking is the killing of prisoners of war. When, during a heated battle, a soldiers sees his comrades fall, one by one, and realizes that defeat in imminent, he may throw down his weapon, raise his arms in surrender, and demand to be treated as prisoner of war. However, there is no guatantee that his enemy will oblige.

We know from having examined officers' war journals that some of them issued orders to kill insubordinate prisoners, but that is to be expected in a conflict, as is the shooting of fleeing stragglers. According to the Rules Respecting Laws and Customs of War on Land, commanding officers have the authority to decide whether or not to take prisoners of war during hostilities. Commanders must make expeditious decisions, based on their instincts and training, because the outcome of the battle, their lives and the lives of their men are at stake. They do not have time to contemplate the possibility that they may be violating international law.

A Study of Combat Methods Used Against Chinese Troops, published by the Infantry School in 1933, contains a section entitled "Disposition of Prisoners of War." Fujiwara Akira's interpretation of the material in this section is that Japanese military authorities instructed their subordinates to refrain from executing Russian or German prisoners of war, but did not discourage the execution of Chinese prisoners.48 Fujiwara has misunderstood the text, which follows.

Any debate concerning Chinese troops disguised as civilians requires a knowledge of the Regulations annexed to the Hague Convention Concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land (1907). According to the Regulations, soldiers wearing civilian clothing do not meet the qualifications of belligerents, which are as follows.

Therefore, individual soldiers (or a group of soldiers) masquerading as civilians cannot be viewed as belligerents. Dr. Shinobu Junpei, Japan's foremost authority on international law, writes:

Those who have embraced the "massacre" argument castigate Japanese military personnel for executing Chinese soldiers masquerading as civilians and carrying concealed weapons without benefit of trial. Perhaps they are unaware of the many, many instances in which Japanese soldiers were caught off guard and killed by those "civilians." In any case, the gist of the aforementioned section of the Infantry School document is: With the exception of those special cases, prisoners of war may be released.

It is true that, at that time, neither commanding officers nor the rank-and-file were not conversant with international law. Therefore, when faced with large numbers of prisoners of war in Nanking, they were at a loss as to how to accommodate them and, in some cases, they made bad decisions.

Such tragedies occur in all wars. To cite an example from the Western world, the portion of World War II fought in the European theater ended on May 8, 1945 when the Germans surrendered. Soon thereafter, 175,000 German soldiers were taken prisoner in Yugoslavia. While crossing the Alps, more than 80,000 of them were slaughtered en masse by Yugoslavian troops. Only about half of them were placed in detention camps. According to The Prisoners: The Lives and Survival of German Soldiers Behind Barbed Wire, written by Paul Carell and Gunter Boddecker,53 many other, similar incidents took place.

Hora Tomio conjectures that Lt.-Gen. Nakajima Kesago, commander of the 16th Division, ordered the mass execution of prisoners of war because the latter wrote "our policy is, in principle, to take no prisoners" in his diary.54 Others, too, have misunderstood this passage and argued that Chinese prisoners taken in Nanking were systematically slaughtered, but that was not at all the case.

Onishi Hajime, former staff officer of the Shanghai Expeditionary Force, provided the following explanation about policy relating to prisoners of war.

Onishi added that no Division order (or any other type of order, for that matter) instructing that prisoners of war be killed was ever issued. Two detention camps were established in Nanking, housing a total of about 10,000 prisoners. Additionally, there was a small facility at Jiangdong Gate where model prisoners were detained, and two other detention camps. According to former Staff Officer Sakakibara Kazue, who was entrusted with the supervision of the prisoners, "I received orders to move half of the 4,000 prisoners held at the Central Prison Camp to the camp in Shanghai. I made the decisions about who would be moved." At the IMTFE, Sakakibara testified that "some of the prisoners were assigned to each unit as laborers. Many escaped, but we didn't try to stop them."56

When a new government (later headed by Wang Jingwei) was established in Nanking, more prisoners were released and reconscripted. Liang Hongzhi, who was instrumental in forming that government, and who served as head of its Executive Yuan, was eventually tried and executed for having collaborated with the Japanese. At his trial, he made the following statement.

In other words, the vast majority of men who comprised the approximately 10,000-man Pacification Forces were former prisoners of war who had surrendered in Nanking or Wuhan. Liu Qixiong, who later served as head of the Beijing New Democracy Society's Supervisory Department, was once a prisoner of war in Nanking.

We shall now describe two cases in which prisoners were released where they were captured. The first involved the 20th Infantry Regiment (from Fukuchiyama), attached to the 16th Division and commanded by Maj.-Gen. Ono Nobuaki. Kinugawa Takeichi, a former member of the 1st Company of that Regiment sent a letter to this writer describing the particulars. An excerpt follows.

The second instance involved the 45th Infantry Regiment (from Kagoshima), commanded by Takeshita Yoshiyasu. Approximately 5,000 Chinese soldiers waving white flags surrendered to the Regiment's 2nd Company at Xiaguan on the morning of December 14. From them the 2nd Company confiscated 30 cannons, as well as heavy machine guns, rifles, an enormous amount of ammunition, and 10 horses. Honda Katsuichi describes the release of these prisoners as follows.

The 65th Infantry Regiment (from Aizu Wakamatsu) under the command of Col. Morozumi Gyosaku, and attached to the 13th Division (commanded by Maj.-Gen. Yamada Senji), took the largest number of prisoners (14,700), on December 14 near Mufushan.

To learn the truth about how these prisoners were treated, writer Suzuki Akira travelled to Sendai in 1962 to interview former Maj.Gen. Yamada and other men who were at Mufushan. His report on those interviews, which we shall summarize here, appears in The Illusion of a Great Nanking Massacre. Maj.-Gen. Yamada thought long and hard, trying to arrive at an equitable decision regarding the treatment of the prisoners. Finally, he decided to transport them to an island in the Yangtze River and release them. However, when they had neared their destination, a riot broke out during which about 1,000 prisoners were shot to death. There were Japanese casualties as well.59 The Fukushima Min Jyu Shinbun carried a series of articles about the incident, which included the testimonies of many Japanese soldiers who were involved in the incident, under the title "Army Campaigns During the Second Sino-Japanese War." The series was later reprinted in a Self-Defense Forces publication.60 In its August 7, 1984 edition, the Mainichi Shinbun printed an article with a banner headline reading: "Former Army Corporal Describes the Massacre of More Than 10,000 Prisoners Taken in Nanking." The article relates the story of a Mr. K., a former corporal in the 65th Regiment, who marched 13,500 prisoners to the banks of the Yangtze and killed all of them. This was a major news story, since it stated that the executions were planned and systematic, contradicting the previously held perception.

Soon after the newspaper article appeared, Honda Katsuichi visited Mr. K., interviewed him, and wrote a two-part article, which ran in two successive issues of the monthly Asahi Journal.61 Honda's articles, which contained more detail, asserted that the executions of 13,500 prisoners had been ordered by Shanghai Expeditionary Force Headquarters.

Mr. K. is, in actuality, Kurihara Riichi, a resident of Tokyo. He sent a protest to the Mainichi Shinbun, in which he stated that he had agreed to an interview because he wished to refute the charge made in Testimonies: The Great Nanking Massacre (supposedly official records) published in China, i.e., that Japanese troops had massacred 300,000-400,000 Chinese. However, the newspaper's reporter had both quoted Mr. Kurihara out of context and attributed statements to him that he had never made. Even though the Mainichi Shinbun didn't print his name, Mr. Kurihara felt that he had been slandered and exploited.

On September 27, in a tiny article bearing the headline "The Eyes of a Reporter," the Mainichi Shinbun summarized Mr. Kurihara's protest. However, the gist of the article was that the criticism that had been heaped on "Mr. K." was shameful. The newspaper offered no apology whatsoever for its reporter's misdeeds.

When I telephoned Mr. Kurihara, hoping to learn what he had really said, he responded: "Both the Mainichi Shinbun and Honda omitted the very points I wished to make. They twisted my words until they had me saying the exact opposite of what I had told them. I regret having spoken to either of them."

I telephoned him again, but when he wouldn't agree to an interview, I decided to fly to Fukushima and meet with Hirabayashi Sadaharu, former sublieutenant and commander of an artillery platoon attached to the 65th Regiment. Since Suzuki Akira's interview with Mr. Hirabayashi appears in the aforementioned The Illusion of a Great Nanking Massacre, we will print only the highlights of what the latter told us.

The March 1985 issue of Zenbo contains the transcript of an interview with Mr. Kurihara, which is virtually identical to Mr. Hirabayashi's testimony. During the interview, Kurihara said, "When I read the article in the Mainichi Shinbun, I was astounded. They put words in my mouth. I told them my story because I wanted to protest the accusation that 300,000 Chinese were massacred, but they made it seem as though I support that claim." About Honda, he commented: "All he does is repeat lies the Chinese told him. I don't think he's in his right mind. I don't know why he bothered to interview me, because he made the whole thing up. I was betrayed."

Mr. Kurihara repeatedly expressed his anger at the Mainichi Shinbun reporter and Honda Katsuichi for misrepresenting him. For instance, he told them that he was in the process of transporting the prisoners to the opposite bank of the Yangtze, where they were to be released. However, in their version of his story, he was portrayed as the mastermind of a massacre.

The media are often referred to as the "fourth estate," because of the power they wield. When a major newspaper runs a sensational article and its editors realize they've made a mistake, they may print a retraction, but the damage has already been done. The fact that they slandered Mr. Kurihara by insinuating that he orchestrated the massacre of 13,000 prisoners was bad enough.63 But far more reprehensible was their abuse of the freedom of speech, for the very reason that their influence on society is so profound. Irresponsible reporting of this sort distorts the perception of history, and insults and disgraces the Japanese people. One cannot help but wonder why these journalists are so intent on advocating a massacre that never occurred, disseminating lies that bring shame on Japan, and collaborating in Chinese propaganda campaigns.

A 167-page book containing 69 missives issued by the International Commitee, and addressed to the Japanese, American, and German embassies. It is one of the most important contemporaneous sources on Nanking.

A 167-page book containing 69 missives issued by the International Commitee, and addressed to the Japanese, American, and German embassies. It is one of the most important contemporaneous sources on Nanking.