| Islamic Architecture in

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

|

Shan xi sheng 陝西省

HUAJUEXIANG MOSQUE ***

Since I have already written on the Huajuexiang Great Mosque of Xian in the chapter ‘Masterpieces of Islamic Architecture’ on my website (please see that page), here I will only write on some of its other aspects, even though there will be some overlap.

Although this is the most famous mosque in China, along with the Niujie Mosque in Beijing, it does not have a proper name in spite of it being referred to by many different names in the past. When it was first constructed in 1392 during the age ruled by Hong Wu Di (r. 1328-98), it was called Shengjiao Si, then Tangming Si, then Huihui Wanshan Si, and then Qingxiu Si (‘si’ means a temple). The current name ‘Qingzhen Dasi’ means Great Mosque or Friday Mosque, and by adding the name of the front street to it, it is officially referred to as the Huajue-xiang Qingzhen Dasi. The word ‘xiang’ literally means alleyway, Huajuexiang is not a main street in Xian but an L-shaped narrow alley, which runs alongside the eastern and northern façades of the mosque. It may have been one of the causes for not having been destroyed during the Cultural Revolution that the mosque did not pompously display its façade to a main street.

This narrow street is always thronged with strollers and shoppers at the street-stalls and stores that line the alleyway, very much like at Asakusa in Japan. Nowadays, there are more souvenir shops than those selling ‘Pure and True foods’ and clothing for Muslims than in a usual ‘Qingzhen Street’.

The courtyards are loosely partitioned from each other by a low wall or a hedge, and it is characteristic that each border has a Chinese style gate. Moreover in the center of the first courtyard is a Mupailou or a monumental wooden gate, in the second is a Shipailou or a monumental stone gate. They are not related with the above-mentioned partitions or the function of the mosque, only considered as independent embellishments. The former wooden one from the early Qing era is particularly magnificent, with its bracket-sets supporting the roof being a substitution of Muqarnas ornament in Middle Eastern architecture.

Therefore, the disposition of these courtyards is remarkably different from those of the Middle East, giving an impression not of having buildings enclose a comfortable space, but of making an extensive space in which to erect a building monumentally in the center. It is unacceptable to call the form of these courtyards ‘Siheyuan’, for they are extremely different from the traditional quadrangle courtyard that is strictly enclosed by four buildings.

The second and third courtyards both have a pair of tablet pavilions on the right and left, on which are recorded the mosque’s restorations. However, the one stone tablet ‘Memoir of royal reconstruction of the Qingzhen Si’, which states that this mosque was reconstructed in the Tang era, is a fake from the Ming era.

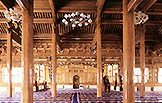

The inmost Great Hall is a seven-spanned stately wooden edifice, which covers an area of about 1,300 square meters. Corresponding to its depth it consists of two buildings ahead and behind, and then a Rear Mihrab Hall added orthogonally at the rear. The front half of the first building is an open colonnaded hall with a high ceiling. It is especially useful as a space for taking off footwear and furling umbrellas on rainy days, as the Great Hall can accommodate 1,000 followers at one time. Si chuan sheng 四川省

BABA MOSQUE ***

The city of Langzhong occupies the whole inside of a U-shape curve of the Jialing River, by virtue of which it has always enjoyed scenic beauty and strong defense. Its townscape, with rows of one-story houses surmounted with black tiled roofs, is extremely quaint with harmonious beauty, particularly when looked down upon from the sole tower in the city, Huaguang Lou, like erstwhile Kyoto in Japan. Although Langzhong was not only designated one of the National Historical Great Cities of China but also counted as one of the Four Completely Preserved Old Cities along with Pingyao, Lijian, and Huangshan, this preserved city is not mentioned in the main travel guidebooks, such as Lonely Planet, so it is not necessarily widely known. In order to reach this city one has to take a long-distance bus at Chengdu, which takes four and a half hours via Nanchong.

Langzhong was once the capital of the state of Ba, currently the eastern part of Sichuan Province, and in the age of the Sanquo (Three Kingdoms) it was the stage for the energetic activity and death of Zhangfei, the great warrior of the Shu Kingdom, so his Mausoleum, Hanhuanhou Si can be found, in the city.

At the hilly section under Mt. Panlong, a little distant from the preserved district in this old city, is located the Baba Si (mosque). A fairly gorgeous mosque gate faces a road on the lower side; it is a kind of Shipailou (stone pylon) with a high central roof and boldly curved eaves that is sustained by colorfully painted bracket sets. Brick walls on both sides are well sculpted. A pilgrim path from here to the mosque goes up through a hillside cemetery with Muslim tombs scattered around in twos and threes among the trees. After a small gate at the mosque precincts one first encounters a fine brick Zhaobi (Mirror Wall), from which the main axis stretches, having all facilities follow it. In front of this Zhaobi is the second gate, also made of brick, from which a wall extends to encircle the central precincts. Going through the second gate, one finds immediately a Mupailou (Wooden Pylon) , also fine. Beyond the courtyard is the wooden Great Hall, but no lecture halls on either side, because actually this is originally a Gongbei (Mausoleum) but a worship space was later added in front, converting it into a mosque.

The tiled roof of the mausoleum itself takes the form of a mountain, rising almost perpendicularly, never seen in Japan. It can be said to be a replaced form for the western masonry dome, by means of wooden structure. Mausoleum is called ‘Qubba’ in Arabic and ‘Gonbad’ in Persian, both of which originally meant dome. Since it has usually been a dome that covers a tomb in the Middle East, a mausoleum itself also came to be called by those names. They were transliterated into Chinese as ‘Gongbei’ or ‘Gongbai’ with Chinese characters, and the result of the intention to express this transliteration in formative art became such a dome-like wooden structures with a tiled roof.

‘Baba’ is originally an Arabic word meaning the ancestor or founder of a religious sect; this mausoleum is the tomb of Wazir Abd al-Nasir, the founder of the Qadir order, one of the four Sufism sects in China. He came to China in the Qing era to propagate Islam and died in Langzhong in 1689, year 28 in the reign of Kangxi. The mausoleum was erected in the same year and a worship hall was added later. However, the name of the mosque ‘Ba’ could also have been related to the ancient state of Ba.

This is a middle sized mosque located inside the preserved district in the old city of Langzhong. Constructed in 1669, year 8 in the reign of Kangxi during the Qing era, this mosque is also designated as a Key Heritage Conservation Unit of Sichuan Province. Si chuan sheng 四川省

HUANGCHENG MOSQUE *

Chengdu, a metropolis with a population of six million, is the capital city of Sichuan Province, and is only 50km from the epicenter of the great Earthquake of Sichuan in May 2008. The city’s name is said to be traced back to the Zhou era B.C.E. Unlike the equivalent ancient town of Xian, medieval Chengdu did not seem to have a Muslim community and it is recorded that the first mosque was established as late as in the Ming era.

It was in 1859 during the Xianfeng period that the mosque was repaired on a large scale, and also in 1919. It was a Chinese style mosque, boasting the largest scale in Sichuan Province, in the midst of a Hui district. However, it was taken down in 1990 during the reordering and enlargement of Tianfu Square, in the center of the city. As seen in the photo of the model, the whole mosque was put on a square artificial ground for the purpose of effective use of the site, which had been made smaller than before, making the lower part a car park, stores, and other utilities. Going up a flight of stairs, one can enter a symmetrical composition of buildings from the gate to the Great Hall. At the edge of the terrace a part of the perimeter wall is higher in order to function as a Zhaobi (Mirror Wall).

A two storied building surmounted with two minarets divides the ground into a forecourt on the road side and a courtyard on the rear. The latter is partitioned by two open corridors into three parts: the right, center, and left. Beyond the courtyard is the tall two-storied Great Hall, which includes the women’s worship hall on the lower floor and the men’s on the upper. Ning xia Hui zu zizhiqu 宁夏回族自治区

NAJIAHU MOSQUE **

The Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, including the cities of Yongning and Tongxin (see next section), is the area that embraces the largest number of Hui people in China. One third of its population, about 1.9 million, is said to belong to this ‘nation’. The plain of Ningxia, blessed with the waters of the Yellow River, has been known as a fertile land since ancient times. The Hui people immigrated from the west and were assimilated with the Han people except for their religion, Islam, which they retained. In the capital city of Yinchuan, the largest Southern Mosque was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution and has been rebuilt now in a western style domed form. Since the Qingzhen Si (mosque) in Shizuishan, north of Yinchuan, was also destroyed, one has to go to Yongning, close to 20km south of Yinchuan, to seek for an old mosque. It is said that this area was settled by Hui people in the Yuan era.

The village of Najiahu is located in the immediate neighborhood of Yongning, having a population of a little over 4,000. 97 percent are Hui people, moreover more than 60 percent of whom have the same surnames, Na, hence comes the village name. The Najiahu Mosque is said to have been first constructed in 1525, the third year of the Jiajing period during the Ming era. An imposing gate for the entrance to the premises, in front of a Zhaobi, was recently built after the reform of the national religious policy. It is made in a mixed structure of brick and wood, with three arched apertures on the ground floor. The upper part is a three storied wooden pavilion accompanied with brick towers on both sides. On account of being more conspicuous than the Great Hall, this gate has become the symbol of the Najiahu Mosque nowadays.

The Great Hall has an independently standing front open hall, which is not a rolled-shed roof building but surmounted with the same gable roof as the rear worship hall. While it is five spans in width, namely 20m, the worship hall is, structurally saying, seven owing to its encircling corridors. The worship hall has increased the number of buildings, of which it consists, through repeated extension. Even when I visited here in 2005, the fourth building was being added at the end of the worship hall, transferring the Mihrab into it. The total length of this Great Hall would now be close to 60m.

Be that as it may, is such a large mosque, able to acomdate 1,500 people at one time, really needed for this small village? It might be now more significant as a cultural heritage than as a practical place of worship.

The interiors are also finished in the same manner, except, on my visit, for the surroundings of the newly established Mihrab, which were entirely carved but not yet painted. Those plain wooden walls looked rather refreshing to my taste. This Mihrab space is not treated as an independent Rear Mihrab Hall, without even a partition from the worship hall, in contrast to the Huajuexiang Mosque in Xian. Ning xia Hui zu zizhiqu 宁夏回族自治区

GREAT MOSQUE **

Tongxin Province in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region has a population of 370,000 people, 80 percent of which are Hui. The Great Mosque of Tongxin, located near the ruined castle to the southwest, is said to have first been built in the age of Wanli (1573-1620) during the Ming era, and is counted as one of the ten great old mosques in China. An inscription in the mosque says that it underwent major repairs in the 56th year of the reign of Qianlong during the Qing era (1791) and in the 33rd year of the Guangxu period toward the end of the same era (1907). According to another account, following the suppression of the Hui revolt by the Qing dynasty the mosque was destroyed in the Tongzhi period, and the current mosque was reconstructed at the end of the Qing era.

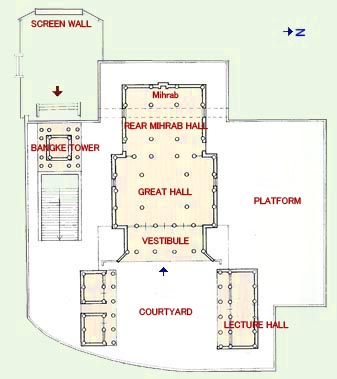

In 1963 when the Red Army of Chinese Workers and Farmers marched to the west the Great Mosque of Tongxin was used as the stage of an important conference, which brought the Hui Autonomous Government into existence for the first time in the history of China. This fact might have been one of the reasons that the mosque was designated as a National Key Heritage Conservation Unit along with the Huajuexiang Mosque of Xian and others, equivalent to National or Important Cultural Treasure in Japan. The composition of the Great Mosque of Tongxin is quite unique: everything, including the courtyard, is on a seven-meter high platform made of brick, looking like a stronghold. The approach to the mosque is dramatic: one goes in one of three contiguous arched apertures through short tunnels under the high Bangke Tower (minaret), and then up a wide flight of stairs to get to the precincts on the platform. As far as I know, such a three-dimensional dramatic arrangement in approach is also seen only at the Sokollu Mosque (1571) in Istanbul, designed by Mimar Sinan. However, in this flat site, as opposed to the slanting ground in Istanbul, the reason for having made such a high platform is not clear, though a small part of it is used as a ritual washing room and for other facilities.

Plan of Great Mosque in Tongxin

The entire site area is 3,500 square meters. From the Zhaopi (mirror wall), in front of the three contiguous arches, there is a main axis going through the Bangke Tower and large stairway, but the direction to Macca is just opposite. One drawback of this layout is that one has to make a U-turn to reach the Great Hall through a courtyard, to which one has to go in through a narrow space between buildings. It is said that there was once a main approach on the east side but it was burned down in a war. As mentioned in the section on Beijin, it can be said that the Chinese style (Siheyuan-like) mosques fail on the whole in the sequential composition of exterior spaces unless entered from the east side.

The Bangke Tower on the second gate is a two-storied square building with a pyramidal roof, functioning also as a moon watching tower. Having more columns than usual on a building of the same scale, a strongly curved roof, and decorative details, the tower is a symbol of the mosque. Although it resembles Japanese Buddhist temple towers, it does not have the nucleus pillar or a ceiling, exposing its overhead structural frame.

The vestibule is an almost independent large portico with a humpbacked roof and the Great Hall is ‘Danyan-xieshan type’ or a single story building with a gambrel roof, consisting of two buildings, front and rear, with a capacity of 800 worshipers. The facade is five-span-wide in spite of having only four pillars inside, generating strangely a gap in east-west column lines.

To visit the Great Mosque of Tongxin, it is recommended to stay one night in Zhongning and get a taxi for a one-day trip to Tongxin. When I visited in 2005, restoration of the mosque was in full swing. There should have also been an important mosque of the 14th century in the same Tongxin Province, Weizhou, 120km from Tongxin, but vexatiously it had been completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution and I found a new uninteresting mosque there after a long drive by taxi from Tongxin. Gan su sheng 甘肃省

WESTERN GREAT MOSQUE *

(Left) The current Western Great Mosque in Lanzhou.

Lanzhou is the capital city of Gansu Province, called Jincheng in old days and got the current name in the remote Sui era.

Plans for a new mosque started in 1983 after religious liberalization, and the Eastern Great Mosque of Lanzhou was constructed in place of the demolished Jiefanglu Mosque. It is also called ‘Ke Si’ (Guest Temple), for it was financially assisted by a foreign affiliated corporation (known in Chinese as guest trade). It was designed by a Hui architect named Wang Honglie, not in the Chinese style but in the ‘Arabic’, with a dome over the four-story building. The first floor is uplifted by a large flight of steps, accommodating a followers’ hall in the semi basement. Inside are, as well as the worship hall, a library, lecture halls, and a women’s mosque. The worship hall is sixteen-agonal on plan with eight pillars in a circle, over which is a two-story high ‘laternendecke’ ceiling.

In China, the movement to preach and diffuse Islam, which started in the Tang era, has a long tradition, and the oldest mainstream school, Qadim, was disrespectfully designated as ‘old teachings’ or ‘aged teachings’, while those who studied directly in the Middle East in the 18th century established Sufi sects in China and referred to them as ‘new teachings’. Among them the Jahriyya Sufi sect founded by Ma Mingxin has a long disastrous history variegated with persecutions and insurgences.

The Gongbei (mausoleum) of Ma Mingxin, martyred in 1781, was located here in Langzhou as the spiritual base for its followers, but was destroyed in 1958 during the Cultural Revolution. The current one of reinforced concrete was reconstructed in the 1980s after religious liberalization. It is surmounted with a bulbous dome over an octagonal circular arcade of pointed arches. The design of the Western Great Mosque might have adopted this image. Gan su sheng 甘肃省

LAOWANG MOSQUE *

The center for Muslims in Gansu Province is the city of Linxia (former Hezhou) with a population of 220,000. It is located in the Linxia Hui Autonomous Region in this province, at 2,000 meters above sea level. There were once twelve Chinese style mosques here in a typical Hui community area filled with traditional courtyard houses outside the south gate of the city, called ‘Eight Districts with Twelve Temples’. However, almost all those mosques were destroyed or abandoned through the onslaught on these districts following the ‘Rebellion of Hezhou’ in 1928 and then the Cultural Revolution. In addition, the redevelopment of the city swept away the traditional residential area, making Linxia similar to other unexceptional cities. Though dozens of mosques, such as the Dahua Mosque, have been built after religious liberalization, there are few that are high-quality from an architectural point of view. Most of them are in ‘Arabic style’ with an ornamental dome. Among Chinese style ones the Laowang Mosque is the most interesting. It is said to have been first constructed in the first year of the reign of Hongwu (1368) and suffered repeated disasters and subsequent restorations many times. It now has a Bangke Tower (minaret), resembling the five-story Buddhist towers in Japan and also functioning as the second gate, just inside a smallish main gate. The Great Hall, lecture halls, and a Madrasa (Koranic school) surround the courtyard. The worship hall and minaret were destroyed in 1968 during the Cultural Revolution and the current buildings were reconstructed from 1980 to 84 after the resuscitation of religions.

Despite being a modern reconstruction, the uniquely-shaped Bangke Tower (minaret), hardly ever seen elsewhere in the world, is a great feature. The minaret was originally called Manara in Arabic, and was variously translated, like ‘tower of light’, and transliterated into Chinese with Kanji characters without special differences in function from each other.

In Linxia live a large number of Hui people, dispersing mosques to every corner of the city, and constantly drawing pilgrims to its Grand Gongbei (Great Mausoleum) as the holy land for their faith, so some people call this place the ‘Macca of China’. Early Islam forbade constructing and worshiping tombs, for those deeds was equated with idolatry. However, similar to the fact that despite original Buddhism not erecting tombs, once it was brought to Japan, the Japanese came to build tombs, following their traditional custom of ancestor-worship, in the same way Muslims also came to erect magnificent tombs combining saint-worship, in the wake of the diffusion of Islam to various parts of the world.

One reason is that as the mosque was a place of worship for men, women came to visit saints’ mausoleums to pray for their aspirations to be fulfilled. In accordance with the developing of Sufism, tombs of saints came to be built for worshiping by pilgrims, evolving mausoleum architecture. The largest scale and most famous is the Da Gongbei (Grand Mausoleum) located in the northwestern region of Linxia. Construction began in the year 59 in the reign of Kangxi (1720), originally around the sacred tomb of Qi Jingyi (1656-1719), who had founded the Qadiriyya Sufi Order (North Menhuan) in China, so it was first called the ‘Qi Family Gongbei’. After the sixth generation chief of the order, Qi Daohe, enlarged its scale, it received its current name ‘Da Gongbei’.

Menhuan, written with Chinese characters, means Sufi orders, the main four of which are referred to as the four grand Chinese Sufi orders, namely the Qadiriyya, Khufiyya, Kubrawiyya, and aforementioned Jahriyya. Since the Qadiriyya possesses this Da Gongbei, it is sometimes called ‘Da Gongbei Menhuan’.

Its precincts are so vast that after the Great Gate and east and west gates there are a line of many building, such as eight mausoleums, an Ahong’s house, a worship hall, the Tranquil Learning Pavilion, a guest room, a students’ house, and the Rear Garden. However, it lacks a master plan and an axis penetrating the premises. It was overall formed by succeeding additions of each portion. Liu Zhiping insisted in his book that this complicated process had brought to the site a more mysterious character and importance, but he did not show its plan.

What is most interesting architecturally are the mausoleums scattered here and there, which resemble Japanese three-storied Buddhist towers. Their hexagonal or octagonal tower walls are made of brick ornamented with subtle carvings. Their eaves cantilevered by Dougong brackets, turn sharply upward and its top roof forms a dome-like round shape covered with tiles, as seen in the Baba Mosque of Langzhong. While the word Gongbei is a linguistic translation from Persian, this is an architectural translation from stone to wooden structure.

In the precincts are brick Zhaobis and demarcation walls everywhere, on which various elaborate carvings are seen like on the walls of mausoleums. These brick carvings have almost the same character as traditional wooden carvings, elaborately depicting landscapes, foliage, still life, and temple sites, best representative of Chinese brick carving art. Qing hai sheng 青海省

EASTERN GREAT MOSQUE **

Xining, the capital of Qinghai Province, is located at an altitude of 2,300m and its Tibetan name is Ziling or Zining. Its population is 2.2 million people, half of which live in the urban area, are an admixture of Han, Hui, Tibetan, and Mongolian peoples. In this quiet city, the core mosque, Dongquan, is quite large, counted as one of the four great mosques in northwestern China together with those of Xian, Lanzhou, and Kashi. Although the Dongquan Mosque (Eastern Great Mosque) is said to have been first constructed in the twelfth year of the rule of the first emperor of the Ming era, Hongwu (1380), its current buildings were all reconstructed in the 20th century. The area of its precincts is as large as 1.7 hectares and the central courtyard is also very large at 4,500 square meters, where 20,000 worshipers can rally at the festivals of Eid. After many times of demolition and restoration, it eventually underwent total reconstruction into its current state in 1976. However, the styles of those buildings are not consistent. The more outward in the precincts from the archaic style Great Hall, the more western style the designs become, which might reflect the earliest erection age of each building and the expansion of the premises.

The Great Gate facing the city’s main street, Dongquan Dajie, is fundamentally a modern three storied building with a square in front. It is surmounted with a Middle Eastern style dome and two minarets as ‘Islamic signs’. As the dome is not derived from internal necessity, its design can be said to be the same kind asthe Japanese erstwhile Diadem Design, such as in the National Museum of Tokyo. It embraces a mosque office and a Koranic school, playing a central role in Islamic education in western China.

When going through the main gate of its ground floor, one can see the calm precincts contrasting with the outer bustling urban area. And then one meets the second gate with five continuous arches, accompanying a hexagonal Bangke tower-cum-moon watching tower on both sides. On top of them, the fourth floor is a wooden style hexagonal pavilion surmounted with a tiled roof, showing a Chino-Arabic eclectic or co-existing design.

Since the mosque precincts have a difference in altitude, the floor level of the second gate is about a meter higher than the Great Gate and is a further two meters higher at the podium of the Great Hall at the inmost point on the central axis. The Great Hall’s floor area is as large as 1,100 square meters, admitting 1,500 worshipers at the same time. On its brick walls and vermilion painted columns is a grand gambrel roof covered with enameled tiles. A Tibetan style gilded pot ornament on its ridge gives an indication of the geographical location of this mosque. The Great Hall shows the typical ‘three to one constitution’ of Chinese mosques, namely a front rolled-shed roof building and worship hall plus the Rear Mihrab Hall. However, the front hall, originally open portico, has been enclosed by glass screens with aluminum sashes between columns, while the original bright paintings on the surface of timbers have been restored. Especially conspicuous is the ‘Ruyi Dougong’ supporting the eaves, bracket-sets protruding 45 degrees to the right and left alternatively. Although their structural role is lessened, their visual effect gives a quite dynamic impression. This method is used mainly in this Qinghai province.

The Rear Mihrab Hall is arranged at a right angle to the worship hall like at the Huajuexiang Mosque of Xian. Its interior forms a highly independent space from the worship hall, to which it is connected through a narrowed aperture and all columns are placed outside to free up the interior. Such a unique manner is seen only in a few mosques, such as Jining, Huangzhong or Wulumuqi. Qing hai sheng 青海省

HONGSHUIQUAN MOSQUE ***

Huangzhong is located 25km from Xining, in the Huangzhong region in the city area of Xining, Qinghai Province. Though it is famed for its enormous Kumbum Monastery, one of the six great monasteries of the Gelug group of Tibetan Buddhism, Hui people have also been living here and have built some fine mosques. The best is the Great Mosque of Hongshuiquan, located on the hill of Qingzhen Xiang. At the end of a hilly approach path and a flight of steps, there stands the wooden Great Gate that has withstood many ages. However, this gate, and the inmost Great Hall too, have considerable contradictions to the drawings of Liu Zhi-ping’s survey in the early 1960s’ in his book “Islamic Architecture in China”. Above all, there is no three-storied Bangke Tower now, and the Great Hall is quite new and neat, but I cannot find any record of the demolition of this mosque during the Cultural Revolution.

Whether it is a reconstruction after demolition or a restoration after aging deterioration or a partial enlargement and repair, all are unclear. To begin with, generally speaking, the Chinese seem not to consider the preservation or restoration of ancient or original forms and styles very important. Even in the cases of reconstruction after the Cultural Revolution’s vandalism, there is usually no intention to restore completely to the original shape, even though original drawings still exist. They tend to enlarge the scale or alter into a new form.  Structural Plan of the Hongshuiquan Mosque in Huangzhong

Although the Great Hall looks as if it keeps the feature and structural system of the original mosque to a considerable degree, the building itself seems to be a reconstructed one. To better understand the current mosque I drew the above structural frame plan based upon photographs I had taken.

Since the worship hall is covered with a single roof regardless of its extensiveness, the exposed frames of the roof structure is majestic. On account of no images in the hall, unlike other religions’ temples full of sacred statues, the interior space of this mosque is truly magnificent. It is an extremely excellent piece of architecture as an astylar pure wooden hall. The connection with the Rear Mihrab Hall is also well designed and the interior is quite bright by virtue of windows applied to all encircling walls except the Qibla wall. The lack of gloom of old mosques indicates this Great Hall’s modernity in construction.

In the Rear Mihrab Hall, the whole western Qibla wall consists of wooden carved panels depicting birds and flowers and Arabic calligraphy, and moreover they all are plain timber except gold color on Arabic letters. Generally this mosque has no color painting, even on the outer bracket-sets.

Another longtime established mosque in Huangzhong is the Rosaeshoge Qingzhen Si (Mosque). It is said to have been first constructed during the Tongzhi period (1865-75) as the courtyard type with four courts, probably resembling the composition of Xian’s great mosque. It is also said that the first and second court areas functioned as elementary and secondary schools and the third was the Great Hall.

Despite its precincts not being so extensive, the Great Hall of the new mosque, under construction at the time of my visit, is quite large in scale, looking almost impossible to make room for a courtyard. |

E-mail to: kamiya@t.email.ne.jp