INTERNATIONAL

MILITARY TRIBUNAL

FOR THE FAR EAST

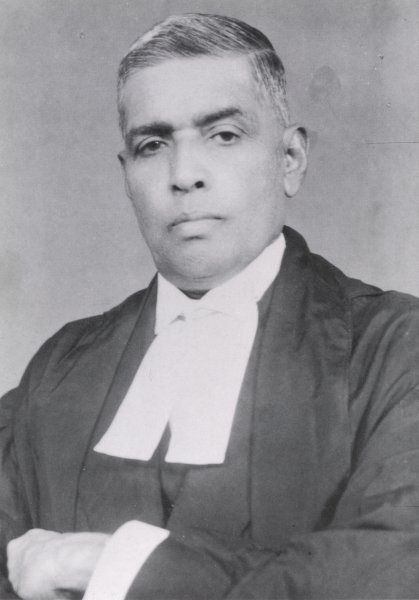

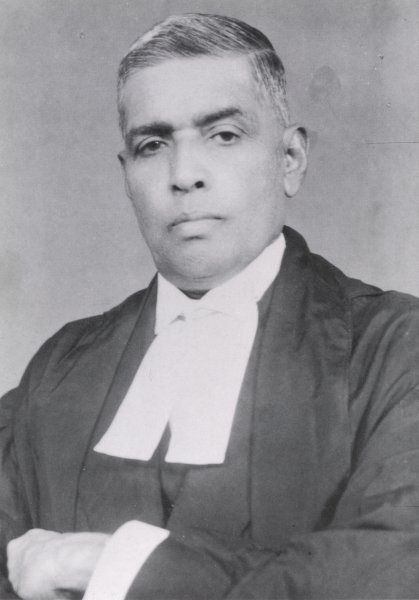

DISSENTIENT JUDGMENT

OF

JUSTICE

PAL

Radhabinod Pal

KOKUSHO-KANKOKAI,Inc.,

Tokyo

1999

|

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

AND OTHERS

Versus

ARAKI SADAO AND OTHERS

JUEGMENT

OF

HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE PAL

Member from India

PART I

PRELIMINARY QUESTION OF LAW

The United States of America, The Republic of China, The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, The Commonwealth of Australia, Canada, The Republic of France, The Kingdom of the Netherlands, New Zealand, India and The Commonwealth of the Philippins.

- Against -

Araki, Sadao; Dohihara, Kenji; Hashimoto, Kingoro; Hata, Shunroku; Hiranuma, Kiichiro; Hirota, Koki; Hoshino, Naoki; Itagaki, Seishiro; Kaya, Okinori; Kido, Koichi; Kimura, Heitaro; Koiso, Kuniaki; Matsui, Iwane; Minami, Jiro; Muto, Akira; Oka, Takasumi; Oshima, Hiroshi; Saro, Kenryo; Shigemitsu, Mamoru; Shimada, shigataro; Shiratori, Toshio; Suzuki, Teiihci; Togo, Shigenori; Tojo, Hideki; Umezu, Yoshijiro.

Defendants.

I sincerely regret my inability to concur in the judgment and decision of my learned brothers. Having regard to the gravity of the case and of the questions of law and of fact involved in it, I feel it my duty to indicate my view of the questions that arise for the decision of this Tribunal.

On April 29, 1946 the eleven prosecuting nations named above filed their indictment against twenty-eight persons. Accused Matsuoka, Yosuke and Nagano, Osami died during the pendency of this trial and accused Okawa, Shumei was discharged from the present proceeding because of his mental incompetency. The remaining twenty-five persons are now arraigned as accused before us to take their trial for what has been stated to be the major warcimes.

Evidence has been given in this case connecting each of the accused with the Government of Japan during the relevant period. Details showing this connection will be given as occasion arises.

The charges against these accused persons are laid in fifty-five counts grouped in three categories:

- Crimes against Peace. (Count 1 to Count 36)

- Murder. (Count 37 to Count 52)

- Conventional War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity. (Count 53 to Count 55).

The counts of charges are prefaced by an introductory summary amply indicating the nature of the prosecution case and are appended with five appendices in the nature of bills of particulars.

In the language of the prosecution itself -

"In Group One, Crimes against Peace as defined in the chapter are charged in thirty-six counts. In the first five counts the accused are charged with conspiracy to secure the military, naval, political and economic domination of certain areas, by the waging of declared or undeclared war or wars of aggression and of war or wars in violation of international law, treaties, agreements and assurances. Count 1 charges that the conspiracy was to secure the domination of East Asia and of the Pacific and Indian Oceans; Count 2, domination of Manchuria; Count 3, domination of all China; Count 4, domination of the same area named in Count 1, by waging such illegal war against sixteen specified countries and peoples. In Count 5, the accused are charged with conspiring with Germany and Italy to secure the domination of the world by the waging of such illegal wars against any opposing countries. The prosecution charges in the next twelve counts (6 to 17) that all or certain accused planned and prepared such illegal wars against twelve nations or people attacked pursuant thereto. In the nextnine counts (18 to 26) it is charged that all or certain accused initiated such illegal wars against eight nations or peoples, identifying in a separate count each nation or people so attacked. In the next ten counts (27 to 36) it is charged that the accused waged such illegal wars against nine nations or peoples, identifying in a separate count each nation or people so warred upon.

"In Group Two, murder or conspiracy to murder is charged in sixteen counts (37 to 52). It is charged, in Count 37, that certain accused conspired unlawfully to kill and murder people of the United States, the Philippines, the British Commonwealth, the Netherlands, and Thailand (Siam), by ordering, causing and permitting Japanese armed forces, in time of peace, to attack those people in violation of Hague Convention III, and in Count 38, in violation of numerous treaties other than Hague Convention III.

"It is charged in the next five counts (39 to 43) that the accused unlawfully killed and murdered the persons indicated in Counts 37 and 38 by ordering, causing and permitting, in time of peace, armed attacks by Japanese armed forces, on December 7 and 8, 1941, at Pearl Harbour, Kota Bahru, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Davao. The accused are charged in the next count (44) with conspiracy to procure and permit the murder of prisoners of war, civilians and crews of torpedoed ships.

"The charges in the last eight counts (45 and 52) of this group are that certain accused , by ordering, causing and pernitted Japanese armed forces unlawfully to attack certain cities in China (Count 45 to 50) and territory in Mongolia and of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (Count 51 to 52), unlawfully killed and murdered large numbers of soldiers and civilians.

"In Group Three, the final group of counts (53 to 55), other conventional War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity, are charged. Certain specified accused are charged in Count 53 with having conspired to order, authorize and permit Japanese commanders, War Ministry officials, police and subordinates to violate treaties and other laws by committing atrocities and other crimes against many thousands of prisoners of war and civilians belonging to the United States, the British Commonwealth, France, Netherlands, the Philippines, China, Portugal and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

"Certain specified accused are directly charged in Count 54 with having ordered, authorized and permitted the persons mentioned in Count 53 to commit offences mentioned in that Count. The same specified accused are charged in the final count (55) with having violated the laws of war by deliberately and recklessly disregarding their legal duty to take adequate steps to secure the observance of conventions, assurances and the laws of war for the protection of prisoners of war and civilians of the nations and peoples named in Count 53."

Summarized particulars in support of the counts in Group One are presented in Appendix A of the Indictment. In Appendix B are collected the Articles of Treaties violated by Japan as charged in the counts for Crimes against Peace and the Crime of Murder. In Appendix C are listed official assurances violated by Japan and incorporated in Group One, Crimes against Peace. Conventions and Assurances concerning the laws and customs of war are discussed in Appendix D, and particulars of breaches of the laws and customs of war for which the accused are responsible are set forth therein. Individual responsibility for crimes set out in the indictment and official positions of responsibility held by each of the accused during the period with which the indictment is concerned are presented in Appendix E.

In presenting its case at the hearing the prosecution offered what it characterized to be "the well-recognized conspiracy method of proof". It undertook to prove:

-

-

that there was an over-all conspiracy;

-

that the said conspiracy was of a comprehensive character and of a continuing nature;

-

that this conspiracy was formed, existed and operated during the period from 1 January, 1928 to 2 September, 1945;

-

that the object and purpose of the said conspiracy consisted in the complete domination by Japan of all the territories generally known as Greater East Asia described in the indictment;

-

that the design of the conspiracy was to secure such domination by

-

war or wars of aggression;

-

war or wars in violation of

-

international law,

- treaties,

-

agreements and assurances;

-

that each accused was a member of this over-all conspiracy at the time any specific crime set forth in any count against him was committed.

The prosecution claimed that as soon as it would succeed in proving the above matters, the guilt of the accused would be established without anything more and that it would not matter whether any particular accused had actually participated in the commission of any specified act or not.

In counts one to five the accused are charged with having participated in the formulation or execution of a common plan or conspiracy, the object of such plan or conspiracy being the military, naval, political and economic domination of certain territories and the means designed for achieving this object being:

-

declared or undeclared war or wars of aggression;

-

war or wars in violation of-

-

international law,

-

treaties,

-

agreements and assurances.

It is implied in these charges that acts in execution of such plan were performed. The accused are sought to be made criminally liable for such acts.

In these counts the questions that would arise for our decision are:

-

Whether military, naval, political and economic domination of one nation by another is a crime in international life;

-

Whether war or wars

-

of aggression,

or

-

in violation of

-

international law,

-

treaties,

-

agreements and assurances

are crimes in international life and whether their legal character would in any way depend upon their being initiated with or without declaration.

Counts six to seventeen charge the accused only with having planned and prepared wars of the categories mentioned above. In order to sustain these charges it is essential that such wars must be criminal or illegal.

Counts eighteen to twenty-four relate to initiation of wars of the same categories and would, therefore, stand or fall according as such wars are or are not crime in international life.

Counts twenty-five to thirty-six charge the accused or some of them with having waged wars of the same categories and would thus fail if such wars are not crime in international life.

Counts thirty-seven to fifty-two contain charges on the footing that hostilities started in breach of treaties would not have the legal character of war and did not therefore confer on the Japanese forces any right of lawful belligerents.

I shall examine these several counts in detail later on. It is obvious that they all involve the question whether wars of the categories mentioned above became crime in international life.

The prosecution case is that these accused persons did the acts alleged in course of working the machinery of the Government of Japan taking advantage of their position in that Government. Grounds of individual responsibility for the alleged crimes are set out in Appendix E of the Indictment thus:

"It is charged against each of the accused that he used the power and prestige of the position which he held and his personal influence in such a manner that he promoted and carried out the offences set out in each Count of this Indictment in which his name appears.

"It is charged against each of the accused that during the periods hereinafter set out against his name he was one of those responsible for all the acts and omissions of the various governments of which he was a member, and of the various civil, military or naval organizations in which he held a position of authority.

"It is charged against each of the accused, as shown by the numbers given after his name, that he was present at and concurred in the decision taken at some of the conferences and cabinet meetings held on or about the following dates in 1941, which decisions prepared for and led to unlawful war on 7 and 8 December, 1941."

The acts alleged are, in my opinion, all acts of state and whatever these accused are alleged to have done, they did that in working the machinery of the government, the duty and responsibility of working the same having fallen on them in due course of events.

Several serious questions of international law would thus arise for our consideration in this case. We cannot take up the questions of fact without coming to a decision on these questions.

The material questions of law that arise for our decision are the following:

-

Whether military, naval, political and economic domination of one nation by another is crime in international life.

-

-

Whether wars of the alleged character became criminal in international law during the period in question in the indictment.

If not,

-

Whether any ex post facto law could be and was enacted making such wars criminal so as to affect the legal character of the acts alleged in the indictment.

-

Whether individuals comprising the government of an alleged aggressor state can be held criminally liable in international law in respect of such acts.

Several subsidiary questions of law will also fall to be decided before we can justly take up the evidence in this case. These questions will be indicated in their proper places in course of the decision of the main questions specified above. But before all this, I must dispose of some PRELIMINARY MATTERS CONCERNING OURSELVES.

The accused at the earliest possible opportunity expressed their apprehension of injustice in the hands of the Tribunal as at present constituted.

The apprehension is that the Members of the Tribunal being representatives of the nations which defeated Japan and which are accusers in this action, the accused cannot expect a fair and impartial trial at their hands and consequently the Tribunal as constituted should not proceed with this trial.

Regarding the Constitution of THE COURT FOR THE TRIAL of persons accused of war crimes, the Advisory Committee of Jurists which met at The Hague in 1920 to prepare the statute for the Permanent Court of International Justice expressed a "voeu" for the establishment of an International Court of Criminal Justice. This, in principle, appears to be a wise solution of the problem, but the plan has not as yet been adopted by the states. Hall suggests that "it should be possible for both the victor and the vanquished in war to be able to bring to trial before AN IMPARTIAL COURT persons who are accused of violating the laws and usages of war".

I feel tempted in this connection to quote the views of Professor Hans Kelsen of the University of California which may have the effect of turning our eyes to one particular side of the picture likely to be lost sight of in a "floodlit court house where only one thing is made to stand out clear for all men to see, namely that the moral conscience of the world is there reasserting the moral dignity of the human race".

The learned Professor says: "It is the jurisdiction of the victorious states over the war criminals of the enemy which the Three Power Declaration signed in Moscow demands ...... It is quite understandable that during the war the peoples who are the victims of the abominable crimes of the Axis Powers wish to take the law in their own hands in order to punish the criminals. But after the war will be over our minds will be open again to the consideration that criminal jurisdiction exercised by the injured states over enemy subjects is considered by the peoples of the delinquents as vengeance rather than justice, and is consequently not the best means to guarantee the future peace. The punishment of war criminals should be an act of international justice, not the satisfaction of a thirst for revenge. It does not quite comply with the idea of international justice that only the vanquished states are obliged to surrender their own subjects to the jurisdiction of an international tribunal for the punishment of war crimes. The victorious states too should be willing to transfer their jurisdiction over their own subjects who have offended the laws of warfare to the same independent and impartial international tribunal."

The learned Professor further says: "As to the question - what kind of tribunal shall be authorized to try war criminals, national or international, there can be little doubt that AN INTERNATIONAL COURT is much more fitted for this task than a national, civil, or military court. Only a court established by an international treaty, to which not only the victorious but also the vanquished states are contracting parties, will not meet with certain difficulties which a national court is confronted with ........."

Though not constituted in the manner suggested by the learned Professor, HERE IS AN INTERNATIONAL TRIBUNAL for the trial of the present accused.

The judges are here no doubt from the different victor nations, but they are here in their personal capacities. One of the essential factors usually considered in the selection of members of such tribunals is MORAL INTEGRITY. This of course embraces more than ordinary fidelity and honesty. It includes "a measure of freedom from prepossessions, a readiness to face the consequences of views which may not be shared, a devotion to judicial processes, and a willingness to make the sacrifices which the performance of judicial duties may involve". The accused persons here have not challenged the constitution of the tribunal on the ground of any shortcoming in any of the members of the tribunal in these respects. The Supreme Commander seems to have given careful and anxious thought to this aspect of the case and there is a provision in the Charter itself permitting the judges to decline to take part in the trial if for any reason they consider that they should not do so.

Ordinarily, on an objection like the one taken in this connection, the judges themselves might have expressed their unwillingness to take upon themselves the responsibility. Administration of justice demands that it should be conducted in such a way as not only to assure that justice is done but also to create the impression that it is being done. In the classic language of Lord Hewart, Lord Chief Justice of England, "It is not merely of some importance, but it is of fundamental importance that justice should not only be done but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done ..... Nothing is to be done which creates even a suspicion that there has been an improper interference with the course of justice". The fear of miscarriage of justice is constantly in the mind of all who are practically or theoretically concerned with the law and especially with the dispensation of criminal law. The special difficulty as to the rule of law governing this case, taken with the ordinary uncertainty as to how far our means are sufficient to detect a crime and coupled further with the awkward possibilities of bias created by racial or political factors, makes our position one of very grave responsibility. The accused cannot be found fault with, if, in these circumstances, they entertain any such apprehension, and I, for myself, fully appreciate the basis of their fear. We cannot condemn the accused if they apprehend, in their trial by a body as we are, any possible interference of emotional factors with objectivity.

We cannot overlook or underestimate the effect of the influence stated above. They may indeed operate even unconsciously. We know how unconscious processes may go on in the mind of anyone who devotes his interest and his energies to finding out how a crime was committed, who committed it, and what were the motives and psychic attitude of the criminal. Since these processes may remain unobserved by the conscious part of the personality and may be influenced only indirectly and remotely by it, they present permanent pitfalls to objective and sound judgment - always discrediting the intergrity of human justice. But in spite of all such obstacles it is human justice with which the accused must rest content. We, on our part, should always keep in view the words of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers with which Mr. Keenan closed his opening statement and avoid the eagerness to accept as real anything that lies in the direction of the unconscious wishes, that comes dangerously near to the aim of the impulses.

With these observations I persuade myself to hold that this objection of the accused need not be upheld.

The defense also took several other objections to the trial; of these the substantial ones may be subdivided under two heads:

-

Those relating strictly to the jurisdiction of the Tribunal.

-

Those which, while assuming the jurisdiction of the Tribunal, call on the Tribunal to discharge the accused of the charges contained in several counts on the ground that they do not disclose any offence at all.

Some of these objections even related to war crimes stricto sensu alleged to have been committed during the war which ended in the surrender. As preliminary objections, these are of no substance.

A war, whether legal or illegal, whether aggressive or defensive, is still a war to be regulated by the accepted rules of warfare. No pact, no convention has in any way abrogated jus-in-bello.

So long as States, or any substantial number of them, still contemplate recourse to war, the principles which are deemed to regulate their conduct as belligerents must still be regarded as constituting a vital part of international law. There is a persistent tendency on the part of the belligerents to shape their conduct according to what they consider to be their own needs rather than the requirements of international justice. Strong measures are required to curb this tendency in the belligerent conduct.

War crimes stricto sensu, as alleged here, refer to acts ascribable to individuals concerned in their individual capacity. These are not acts of State and consequently the principle that no State has jurisdiction over the acts of another State does not apply to this case.

Oppenheim says: "The right of the belligerent to punish, during the war, such war criminals as fall into his hands is a well-recognized principle of international law. It is a right of which he may effectively avail himself as he has occupied all or part of enemy territory, and is thus in the position to seize war criminals who happen to be there. He may, as a condition of the armistice, impose upon the authorities of the defeated state the duty to hand over persons charged with having committed war crimes, regardless of whether such persons are present in the territory actually occupied by him or in the territory which, at the successful end of hostilities, he is in the position to occupy. For in both cases the accused are, in effect, in his power. And, although normally the Treaty of Peace brings to an end the right to prosecute war criminals, no rule of international law prevents the victorious belligerent from imposing upon the defeated State the duty, as one of the provisions of the armistice or of the Peace Treaty, to surrender for trial persons accused of war crimes."

Similar views are expressed by Hall and Garner.

"The principle", says Garner, "that the individual soldier who commits acts in violation of the laws of war, when these acts are at the same time offences against the general criminal law, should be liable to trial and punishment, not only by the courts of his own state, but also by the courts of the injured adversary in case he falls into the hands of the authorities thereof, has long been maintained ......"

Hall says: "A belligerent, besides having the rights over his enemy which flow directly from the right to attack, possesses also the right of punishing persons who have violated the laws of war, if they afterwards fall into his hands ....... To the exercise of the first of the above-mentioned rights no objection can be felt so long as the belligerent confines himself to punishing breaches of UNIVERSALLY ACKNOWLEDGED LAWS."

It should only be remembered that this rule applies only where the crime in question is not an act of state. The statement that if an act is forbidden by international law as a war crime, the perpetrator may be punished by the injured state if he falls in its hands is correct only with this limitation that the act in question is not an act of the enemy state.

IN MYJUDGMENT, it is now well-settled that mere high position of the parties in their respective states would not exonerate them from criminal responsibility in this respect, if, of course, the guilt can otherwise be brought home to them. Their position in the State does not make every act of theirs an act of state within the meaning of international law.

The first substantial objection relating to the jurisdiction of the Tribunal is that the GRIMES TRIABLE BY THIS TRIBUNAL MUST BE LIMITED TO THOSE COMMITTED IN OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE WAR WHICH ENDED IN THE SURRENDER on 2 September, 1945. In my judgment this objection must be sustained. It is preposterous to think that defeat in a war should subject the defeated nation and its nationals to trial for all the delinquencies of their entire existence. There is nothing in the Potsdam Declaration and in the Instrument of Surrender which would entitle the Supreme Commander or the Allied Powers to proceed against the persons who might have committed crimes in or in connection with ANY OTHER WAR.

The prosecution places strong reliance on the CAIRO DECLARATION read with paragraph 8 of the Potsdam Declaration and urges that the Cairo Declaration by expressly referring to all the acts of aggression by Japan since the First World War in 1914 vested the Allied Powers with all possible authority in respect to those incidents. The relevant passage in the CAIRO DECLARATION RUNS THUS: "It is their purpose that Japan shall be stripped of all the islands in the Pacific which she has seized or occupied since the beginning of the First World War in 1914, and that all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and the Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China. Japan will also be expelled from all other territories which she has taken by violence and greed. The aforesaid three great powers, mindful of the enslavement of the people of Korea, are determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent."

THE POTSDAM DECLARATION in paragraph 8 says: "The terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out and Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine."

THESE DECLARATIONS ARE MERE ANNOUNCEMENTS OF THE INTENTION OF THE ALLIED POWERS. They have no legal value. They do not by themselves give rise to any legal right in the United Nations. The Allied Powers themselves disown any contractual relation with the vanquished on the footing of these Declarations: Vide paragraph 3 of the Authority of the Supreme Commander.

As I READ THESE DECLARATIONS I do not find anything in them which will amount even to an announcement of intention on the part of the declarants to try and punish war criminals in relation to these incidents. I am prepared to go further. In my judgment, even if we assume that these Declarations can be read so as to cover such cases, that would not carry us far. The Allied Powers

“Ś‹žŤŮ”»Ž‘—ż‚ÖŠŇ‚é

back to Tokyo Trial Documents