ウィキペディア

ウィキペディア「歌舞伎」は、日本固有の演劇で、重要無形文化財に指定されている伝統芸能です。

“Kabuki 歌舞伎” is a traditional Japanese performing art that has been designated

as an important intangible cultural asset.

2009(平成21)年に国連教育科学文化機関「ユネスコ」の「人類の無形文化遺産の代表リスト」に載りました。

In 2009,

“Kabuki” was listed on the “Intangible Cultural Heritage” list of the United

Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization “UNESCO”.

「歌舞伎」の演目は、「人形浄瑠璃」と同じ様に二つに分類することができます。

The programs

of “Kabuki” can be classified into two categories as “Ningyō-jōruri 人形浄瑠璃”.

一つは「時代物」で、もう一つは「世話物」です。

One is

“Jidai-mono 時代物 Histrical program” and the other is “Sewa-mono 世話物 Gossip program”,

“Jidai-mono

Program” is a program that arranges creativity and legends based on the history

of distant past, and “Kuge 公家 Court noble” and “Bushi

武士 Samurai” are the main characters.

“Sewa-mono

Program” is based on life in the “Edo-jidai 江戸時代 Period”, and characters are mostly the common people.

「人形浄瑠璃」の「脚本」を取り入れた「歌舞伎」は「義太夫狂言」と呼ばれ、現在でも数多く上演されています。

“Kabuki”,

which incorporates “Kyakuhon 脚本 Book” of “Ningyō Jōruri”, is called “Gidayū Kyōgen 義太夫狂言” and is still performed many times now.

It was

after the mid-18th century that “Kabuki” surpassed “Ningyō Jōruri” with its

original programs.

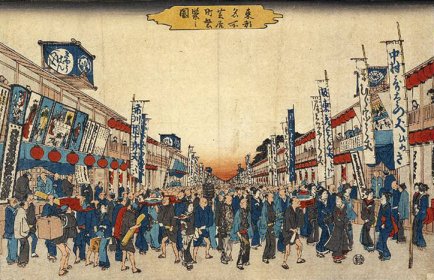

1624(寛永元)年に京で「猿若舞」を創始した「狂言師」の「猿若勘三郎」が、現在の京橋のあたりに「猿若座」の櫓をあげました。

In 1624 (Kan-ei

1), the “Kyōgen-shi 狂言師 Actor” “Saruwaka Kanzaburō”, who

started “Saruwaka Mai 猿若舞 Dance” in Kyoto, raised “Yagura 櫓 Sing tower” of “Saruwaka-za 猿若座 House” around “Kyobashi

京橋”.

“Bugyōsho

(Bakufu) 奉行所(幕府) Public office of Shogunate” gave

permission to “Yarō Kabuki 野郎歌舞伎 Male Kabuki”

under the approval system to prevent the playhouse from being overrun.

In

addition, “Yūjo Kabuki 遊女歌舞伎” (1629) and “Wakashū

Kabuki 若衆歌舞伎” (1652) were banned because they

disturbed the morals.

In 1644,

“Kabuki” using real names was banned, and in 1703 (Genroku 16), the “Ako-jiken 赤穂事件Incident” was happened, and it was also prohibited to adapt the

actual case.

By the

1670s, “Nakamura-za 中村座”, “Ichimura-za 市村座”, “Morita-za 守田座”, “Yamamura-za 山村座” (Edo Yoza-za 江戸四座) were allowed to

perform.

In 1714

(Shōtoku 4), “Yamamura-za” was closed in “Ejima Ikushima-jiken 江島生島事件 Incident”.

In 1841

(Tenpō 12), “Nakamura-za” was burnt down due to a misfire, the fire spread, “Ichimura-za”

was also burnt down.

The

“Satsuma-za 薩摩座 House” of “Jōruri 浄瑠璃 Tale” and “Yūki-za 結城座 House” of “Ningyō

Jōruri 人形浄瑠璃” were also suffered.

“Kawasakizaki-za”

was also moved to “Seitencho” and moved in 1843.

“Shōden-machi”

was renamed “Saruwaka-machi” after “Saruwaka Kansaburō”, the pioneer of the

playhouse in Edo.

In

“Saruwaka-machi”, “San-za 三座 Three theaters”

organized by “Nakamura-za”, “Ichimura-za” and “Morita-za (Kawasakizaki-za)” are

linked together, the programs were enriched.

The visitors

who also visited in “Sensō-ji 浅草寺Temple” came to “Saruwaka-machi”,

and “Kabuki” became more successful than ever.

「歌舞伎」には多くの注目すべき特徴があります。

There are many remarkable features of “Kabuki”.

女性役を専門とする「女方」の存在もその一つです。

The existence of “Onnagata 女形 Actor”, the specialists in female roles is one of them.

From the

end of “Azuchi-Momoyama-jidai 安土桃山時代 Period

(1573-1603)” to the early “Edo-jidai 江戸時代 Period

(1603-1868)”, it was popular in Kyoto to get eye-catching with flashy costumes

and actions.

They

were called “Kabuki-mono かぶき者 Person” because

of their “Kabuku 傾く” meanings of unusual appearances and

actions that would be noticeable.

そして、京都の「加茂川」の河原に舞台をつくり、「かぶき者」をまねた衣装で官能的な踊りと寸劇を演じる「遊女」たちがいました。

And there

were “Yūjo 遊女 Prostitute” who set up a stage on the

riverbank of “Kamo-gawa 鴨川 River” in Kyoto and

performed erotic dances and skits with wore costumes like “Kabuki-mono Person”.

They were

in charge of “Joyū 女優 Actress” combined with “Shōfu/ Yūjo 娼婦/遊女 Prostitute”.

This new

performing art was called “Kabuki-odori 歌舞妓踊り Dance” or “Yūjo

Kabuki 遊女歌舞妓”, and spread throughout the country.

In

Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo, “Waka-shū Kabuki 若衆歌舞伎”, played by young males, became popular.

“Waka-shū

若衆 Apprentice of actors” were called “Kagema 陰間 Stagehand” and also worked as “Danshō 男娼 Male prostitute”.

Many

incidents of fight or bruise occurred scrambling for “Yūjo Prostitute” or “Kagema Male prostiture”.

For this

reason, “Bakufu 幕府 Shogunate” banned “Yūjo Kabuki” in 1629 (Kan-ei 6), and later banned “Wakashū

Kabuki”.

Instead

of a woman, a male performer in the role of a woman called “Onnagata 女方 Actor” was required for “Kabuki”.

「女方」は、単に本物の女性を真似ているだけではなく、約400年にわたって継承・発展してきた芸術的な理想の女性像を演じます。“Onnagata Actor” is not only imitates a real woman, but also performs as an idealistic female figure that has been inherited and developed for about 400 years.

ウィキペディア

ウィキペディア

俳優(役者)の演技を助ける「後見」は、「能」や「狂言」にも登場する日本の伝統芸能の発明です。

“Kōken

“Kōken”

appears on stage in various costumes including “Montsuki-Hakama

“Kōken”

who hides his face in a black “Sha

“Kurogo”

assists actors on the stage to ensure that their performance continues without

interruption and the actors can perform their best.

The

actor's apprentice serves as a “Kurogo,” whose role is to hand out props, clean

up, and arrange costumes.

Thanks

to “Kurogo”, the audience can experience shock and excitement.

For

example, when an actor dances and changes costumes, the audience does not know

how they changed.

Also,

when an actor changes from one character to another, the audience does not know

how the characters are quickly switched.

In one

famous performance, a wicked priest suddenly changes into the young hero in

front of the audience's eyes.

Everything

is different, from wigs to costumes and props, but one actor play both the

priest and the hero.

In

“Kabuki” and “Ningyō-Jōruri 人形浄瑠璃”, “Kurogo” does

not exist on the stage because there is a theatrical and traditional tacit rule

that black is invisible.

In a

snow scene or sea scene, “Kurogo” sometimes changes his black costume for a

white costume or light blue costume.

In these

cases, he is called “Yukigo 雪衣” or “Namigo 波衣”.

In

addition, “Ōdōgu-gata 大道具方 Person in charge of the big tool of

stage” may become “Kurogo” and change the background.

Nowadays

“Kurogo 黒衣” also means someone who prompts others

as metaphor.

「歌舞伎」の舞台には独特の構造と装置があり、「歌舞伎」をさらに魅力的にしています。

The

stage of “Kabuki” has a unique structure and machineries, and that makes “Kabuki”

more attractive.

“Kamite 上手 Stage left” is the right hand side as audiences and “Shimote 下手 State right” is the left hand side as audiences.

The hero

or the heroine appears from “Kamite”.

1718(享保3)年、屋外で行われていた「歌舞伎」の舞台に屋根がつけられました。

In 1718 (Kyōho 3), a roof was added to the

stage of “Kabuki”, which was held outdoors.

“Seri

“Mawari-butai

廻り舞台 Revolving stage” can turns 360 degrees.

It is

possible to change the stage quickly by preparing another set on the back side

of “Mawari-butai Revolving stage”.

In

addition, it is possible to produce a large ship rotating or a small ship

approaching from a distance.

「享保年間(1716-1736)」に「回り舞台」を舞台の下で「人足」が動かす仕組みが開発されました。

In “Kyōho-nenkan

享保年間(1716-1736)Era”, a mechanism was developed to move by

“Ninsoku 人足 Laboer” under the stage of the “Mawari-butai”.

The word

“En no shita no chikara-moti 縁の下の力持ち Powerful men

under the stage” means a person who makes efforts and struggles secretly.

“Hanamichi

花道 Passageway” runs straight through the auditorium from “Toya 鳥屋Waiting space in the back of the auditorium” to “Shimote Stage right”

at the same height as the stage.

A scene

where the main character appears or leaves through “Hanamichi” is a highlight

of the show.

“Hanamichi”

changes into various ways including the seashore, the aisle of a castle, or the

road, according to the performance.

In “Kamite

State left” and “Toya Waiting space”, “Agemaku 揚幕 Curtain” are hanged and the actors come in and out.

When “Agemaku”

will be open, “Kanawa 金輪 Metal ring” that hang “Agemaku” will

sound “Charin チャリン Clank” and will be notified of the

appearance of the actors.

There is

“Seri Lift” called “Suppon スッポン” in the place

called “Shichi-san 七三” near the stage of “Hanamichi”.

By

appearing using “Suppon”, it expresses that the character is an existence with

a special ability.

Originally, “Hanamichi” was made for the

audience to bring flowers to the actors.

「歌舞伎」では、舞台上で演奏される音楽と、舞台の陰で演奏される音楽の両方を楽しむことができます。

In “Kabuki”,

there is both onstage music and offstage music to enjoy.

You can

hear music with playing traditional instruments such as “Taiko 太鼓 Japanese drums”, “Shamisen 三味線 Three-stringed

Japanese instrument” and “Yoko-bue 横笛 Flutes”, all

performed as part of the live play.

“Takemoto

竹本 Narrator” appears on the stage as a narrator in charge of a performance

called “Gidayū Kyōgen 義太夫狂言”.

“Takemoto Narrator” consists of “Dayū,” who speaks with emotional and powerful

excitement, and a shamisen player.

「竹本」は、舞台上手の「床」に座って語ります。

“Takemoto”

sits on the “Yuka 床” at the stage left and narrates.

At the

beginning of the program, etc., “Takemoto” perform in the “Misu

Indispensable

for creating the atmosphere and mood of seines is the music played in the room

called “Kuromisu

演奏者は「簾(すだれ)」を通して舞台の様子を見ながら芝居の進行に合わせて「下座(効果音としての音楽)」を演奏します。The performer plays “Geza

For

example, music expresses various scenes such as spring breeze with butterflies,

thunder in the hot summer evening, boats floating in the river, falling snow,

and a majestic palace.

「歌舞伎」には、他の芸術形式では見ることができないユニークな演技スタイルがあります。

“Kabuki”

has a unique acting style that cannot be seen in other art forms.

For

example, the colorful lines of makeup on the actors' face and body, magnificent

poses larger than the actual movement, and sometimes the screams you hear are all

thrilling in their impact.

These

are the typical style “Aragoto Wild play” that are occasionally used to produce

masculine heroes.

“Aragoto

荒事

Wild play” was founded by the first “Ichikawa Danjūrō 市川團十郎” in Edo in the “Genroku 元禄 Era (1688-1704)”.

On the

other hand, there is also a style called “Wagoto 和事 Gentle play” that gentle and romantic men appear, and that is often

amusing and delightful to watch.

You can

see unique performances such as “Mine 見得 Play” and “Roppō 六方 Play” in “Aragoto Wild play”.

“Mie Play”

is an expression in which the characters perform strong emotions and conflicts

like stop motion tableau.

For greater emphasis, “Mie Play” is accompanied by loud beats of “Hyōshigi

拍子木 Wooden clappers”.

The actor presents the scene to the audience like “photographs” by “Mie

Play”, and gives special stimuli to the audience's visual and auditory

senses.

“Roppō Play” is an act of walking while shaking his hands and striking

his feet.

In addition, “Mie Play” is also performed in the stylized battle scene

called “Tachimawari 立廻り Scene”.

In this

scene, a hero and multiple enemies slash and fight with choreographed movements

including leaps and somersaults.

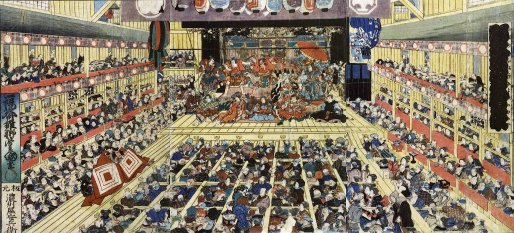

安政年間の市村座『暫』 ウィキペディア

安政年間の市村座『暫』 ウィキペディア

衣装は、シンプルで現実的なものから、世界の劇場の歴史の中で最も途方もなく奇抜に発想されたものまであります!

Costumes

range from the simple and realistic to some of the most extraordinary and

outlandish inventions in the history of world theatre.

The main

character of “Aragoto 荒事 Performances” wears an exaggerated and

visually stunning costume with a makeup called “Kumadori 隈取 Make up”.

You can

also enjoy the skillful manipulation of costumes that are not always easy for

an actor to wear.

“Onnagata

女方 Actor”, who plays the prestigious “Oiran 花魁 Coutesan”, wears luxurious costumes and wigs with extravagant sashes

and many precious hair ornaments.

The sashes

are very expensive, handmade by the most skillful artisans, with genuine gold

and silver threads used frequently and luxuriously.

「隈取(くまどり)」は、元々、顔の血管や筋を強調するために描かれたと言われています。

“Kumadori

Make up” is originally said to have been drawn to emphasize facial blood

vessels and muscles.

“Red” is

used for courage / justice / strength, “Ai-iro 藍色 Indigo” is used for large-scale “Kataki-yaki 敵役 Enemy role”, “Brown” is used for “demons” and “Yōkai 妖怪 Hobgoblin”.

江戸東京博物館

江戸東京博物館

「歌舞伎」を見ると、公演中の叫び声に驚かれるかもしれません。

When you

watch “kabuki”, you might be startled by shouts during the performance.

観客席から舞台へ向かって叫ぶ観客がいるのです。

There

are spectators who scream from the audience seats to the stage.

「歌舞伎」では、俳優と観客とがとても近い関係になります。

In “Kabuki”,

the actors and audience become very close.

それを証明するように、観客の一部が、俳優への称賛と激励のために、演技や踊りの最中に、叫びます。

To prove

it, some audience members shout out during the plays or dances as applause and

encouragement to the actors.

タクシーを呼ぶニューヨーカーのような大きな叫び声がバルコニーから突然に発せされます。

Staccato

shouts, like the clamor of New Yorkers hailing taxi cabs, hurtles down from the

balcony seats in loud.

「掛け声」と呼ばれるこの伝統的な習慣は、劇場の雰囲気を盛り上げます。

This

traditional practice, called “Kakegoe 掛け声 Shout”, adds a

lot to the atmosphere of the theatre.

「江戸時代」は、舞台から最も離れた2階席から客が声を掛けていました。

During “Edo-jidai

江戸時代Period”, audiences shouted from the second floor seats that was the most

far from the stage.

その席は、「大向こう(おおむこう)」と呼ばれていました。

Those

seats has been called “Ōmukō 大向こう Back balcony”

「江戸時代」の「大向こう」は、現代の「一幕見」の立見席に相当します。

The “Ōmukō” in the “Edo-jidai Period” is equivalent to the standing seat

of the modern “Hitomakumi 一幕見 Appreciation of one act”.

「掛け声」は、役者の「屋号」や「代数」などで、熟達したポーズや演技を評価します。

“Kakegoe”

is the “Yagō

現代の「歌舞伎」では、「掛け声」を掛ける人を「大向こう」と呼び、3階または4階の席にいます。

In

modern “Kabuki”, people who shout “Kakegoe” are called “Ōmukō” and are at seats

on the 3rd or 4th floor.

2020年に「十三代目」を襲名する「市川團十郎」には、「成田屋」や「十三代目」などと声を掛けることでしょう。

“Ichikawa

Dunjūrō 市川團十郎” will be call “Narita-ya 成田屋” or “Jūsan-daime 十三代目 Thirteenth

generation” in 2020.

彼らは、伝統的な芸術の知識に誇りを持っている「歌舞通」です。

They are

“Kabuki-tsu 歌舞伎通 Experts” who pride themselves on

their knowledge of traditional art.

日本人は「掛け声」を、芸術のレベルまで高めました。

The

Japanese have refined “Kakegoe” to the level of an art.

現在、いくつかの「掛け声グループは「歌舞”」劇場への無料パスを持っています。

Now,

several “Kakegoe group” have free passes to “Kabuki” theaters.

「江戸時代」は、「侍」と一般庶民(商人、労働者、農民など)との厳しい階層の時代でした。

“Edo-jidai

Period” was a time of rigid hierarchy with “Samurai

「侍」は洗練された方法で「能」と「狂言」を鑑賞しました。

“Samurai”

attended “Nō 能 Noh play” and “Kyōgen 狂言 Kyogen play” theater in a refined manner.

これらとは異なり、「歌舞伎」の劇場は一般庶民のためのもので、俳優と観客とのコミュニケーションが重要だったのです。

“Kabuki”,

theater for the commoners, where communication between the actors and their

audience was important, was quite different.

一般庶民よりもさらに下位にランクされ、俳優は姓を許可されず、17世紀の終わりに発展した「屋号」は、苗字に代わる何かを求める欲求から生まれました。

Ranked even lower than the commoners, actors were not allowed surnames

and the “Yagō”, which developed at the end of the seventeenth century,

came from their desire for something more than a first name.

演技力の低い役者に「大根」と声を掛けたり、「掛け声」を間違えた「大向こう」に「百姓」と声を掛けたりするのは、劇場の楽しい雰囲気の一部でした。

Screaming

out “Daikon 大根 Radish” at a poor performer or “Hyakushō 百姓 Farmer” at “Ōmukō” who fluffs his call was part of the fun atmosphere of

a theater.

「屋号」、「代目」、「大頭領」または「待ってました」は、今日、一般的な呼び方です。

“Yagō”, “Daime 代目”, “Daitōryō 大頭領 Great leader” or “Mattemashita 待ってました We have been waiting” are the usual calls today.

「屋号」の巧みな呼びかけと、たびたびの聴衆の拍手は、共に、良い俳優を育てる助けとなります。

Both the skillful calling of “Yagō” and the clapping of the regular audience

help nurture good actors.