十返舎一九 出典:ウィキペディア

十返舎一九 出典:ウィキペディアチンドン屋は、「滑稽鳴り物入り路傍広告業」とも表現され、3人から5人ほどの編成で、街路を演奏しながら練り歩きます。

Skipping and dancing, they disappear down an alley only to re-emerge from another.

1853(嘉永6)年のペリー来航以来、多くの日本人が西洋音楽による軍楽隊の演奏に驚いたことでしょう。

幕末以降、西洋式軍事力の増強と共に軍楽隊の重要性の認識されるようになりました。

そして、西洋の楽器を演奏する音楽隊は、広告効果を高める手段として着目されました。

かつて、静かな街路において、チンドン屋はとても目立つ存在でした。

In the old day there was less street noise and the chindonya were very

loud and cospicuous.

チンドン屋の名称で定着したのは昭和に入ってからです。

This name came into use during the early Showa Era(1926-1989).

チンドン屋は街頭広告の手法として伝統があり、明治時代に遡ることができます。

The chindonya is the last of a tradition of street advertising.Chindon tradition dates back to the Meiji Era(1868-1912)

その当時、東西屋や広目屋と呼ばれていました。

Then they were called tozaiya or hiromeya.

1886(明治19)年、銀座の木村屋パン店は、洋装でシルクハット姿の楽団を使って、連日にわたって東京市中で宣伝をして回わったそうです。

明治時代中期、海軍の軍楽隊出身者などによって、民間の市中音楽隊(大正時代はジンタと呼ばれます)が生まれ、大規模な楽隊広告が盛んになりました。

その後、乱立気味になったため、サーカス、映画館等の客寄せのために街頭宣伝をするようになりました。

In those times, jinta, or street musicians, who later accompanied silent films, performed the same type of street advertising.

しかし、洋楽演奏と派手な衣装の楽隊広告は、1910(明治43)年に東京都で規制されました。

楽隊広告の管楽器演奏者は、転職を余儀なくされます。

市中音楽隊は、滅亡の一途をたどり、楽隊による街頭広告は小規模なチンドン屋が担うようになります。

また、無声映画の時代は活動弁士による解説と共に、上映に際し楽士に寄る伴奏がつきました。

しかし、徐々にトーキー映画の普及によって楽士は職を失いました。

映画の人気が高まることで職を失った大衆演劇の俳優もチンドン屋に転職しました。

When the talkies started, these musicians lost their jobs.

The movie had a hight popularity, a lot of itinerant actors and actresses

lost their jobs, too.

Many of them became chindonya.

これによって、独特なスタイルが形成されていったと想像されます。

先頭は旗もち(または旗踊り)で、幟を持って歩き、チラシを配ります。

The one who heads the group as they proceed down the street is the hatamochi(or

hataodori)who carries a flag and gives out leaflets.

その後に、締太鼓と鉦を組み合わせたチンドン太鼓を胸の前に担いだ親方が続きます。チンドン太鼓には和傘が開いた状態で固定されています。

He or she is followed by the oyakata the boss, who carries the chindon

drums with their large paper umbrella propped up over them.

行列の3番目は三味線弾きですが、今は大きな太鼓を持ったドラム屋に代わりました。

The third in procession used to play the shamisen, but now is the doramuya,

with one large drum.

さらに、4番目が楽器屋です。クラリネットやサックス、トランペットを吹く楽士が続きます。

And the fouth is the gakkiya, or musician, who plays the saxophone, clarinet,

trumpet, in that order of popularity.

鉦と太鼓が奏でる「チン」と「ドン」の音がチンドン屋の名称の由来とも言われています。

The name chindonya comes from the sound of the leader's metal and leather

drums which make a "chin"and"don"sound.

親方が叩く独特なリズムの鉦の音が、チンドン屋の正式なアナウンスです。

The leader clanging his metal gong while making official-sounding announcements.

全員が「背負いビラ」といわれる宣伝用のポスターを背中に着けています。

楽士以外はカツラをかぶり、ドウランを厚塗りします。

スパンコールをちりばめた時代劇のような衣装を身に着けます。

And an eccentric combination of old Japanese clothing adorend with sequins.

楽士は、古い時代の西洋風のダンディな上着を着て、しゃれたポークパイ帽(フェルト製のソフト帽)をかぶります。

The musician is dressed like an old-time Westernized dandy jacket, tie,

and a rakish porkpie hat.

戦後の復興期から高度成長の時代も、商店街を活気づける存在として欠かせませんでした。

物売りは、鳴り物を鳴らしたり、独特の売り声を発しながら路上を移動し、物品の販売、食事の提供、修理、古物や廃品の買取や交換などをします。

夜、屋台でラーメンを提供する人(夜鳴きラーメン?)の笛は、独特の3つの音色です。

The night ramen vendor's whistle is distinctive three toned.

呼子といわれる笛を宵に吹いて日本蕎麦を売る物売りは、「夜鳴き蕎麦」と呼ばれました。

やがて、日本蕎麦から中華蕎麦(ラーメン)になり、笛もチャルメラに代わりました。

東京の下町では、包丁研ぎや物干しざお売りの声をまだ聞くことができます。

The knife sharpener or the bamboo sellers can still be heard in Tokyo's shitamachi (old, working-class neighborhoods).

焼きいも屋さんの呼び声は、誰でも認識することができます。

Certainly one call that everyone can recognize is the yakiimo man's.

物売りは、食べ物や道具、玩具、薬、日用雑貨だけでなく、古着や傘、金属などを買ったり、包丁や下駄などの修理人としてサービスを提供しました。

They not only sold food, tools, toys, medicine, and small things for daily

use, but some also bought used articles such as old clothes, umbrellas,

and metal and still others served as repairmen for knives, colgs, and the

like.

新年の装飾や端午の節句の菖蒲、夏の金魚、お盆の提灯、夏に子供のための虫など、季節の商品に特化する物売りもいました。

Some monouri specialized in seasonal goods such as decorations for the Hew Year, irises for Boy's Day, goldfish for summer, lanterns for Obon, and insects for children in the summer.

物売りの生活はとても厳しいものです。

The life of the monouri was a hard one.

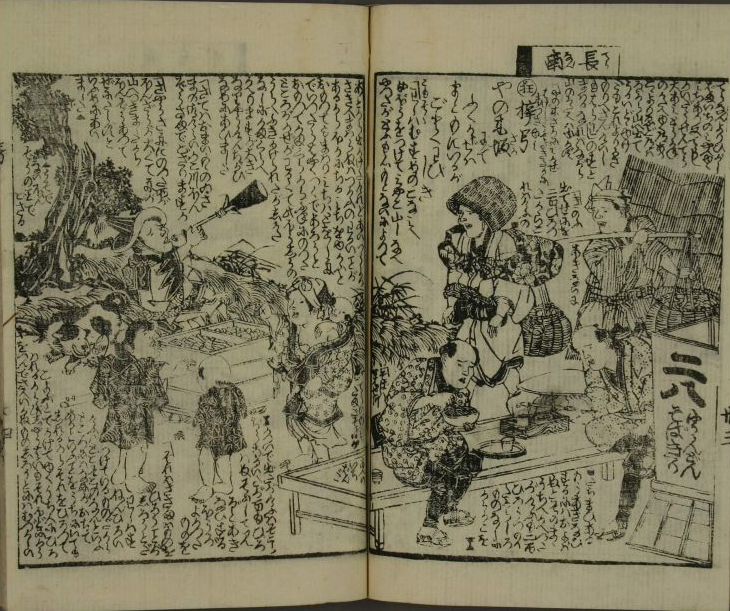

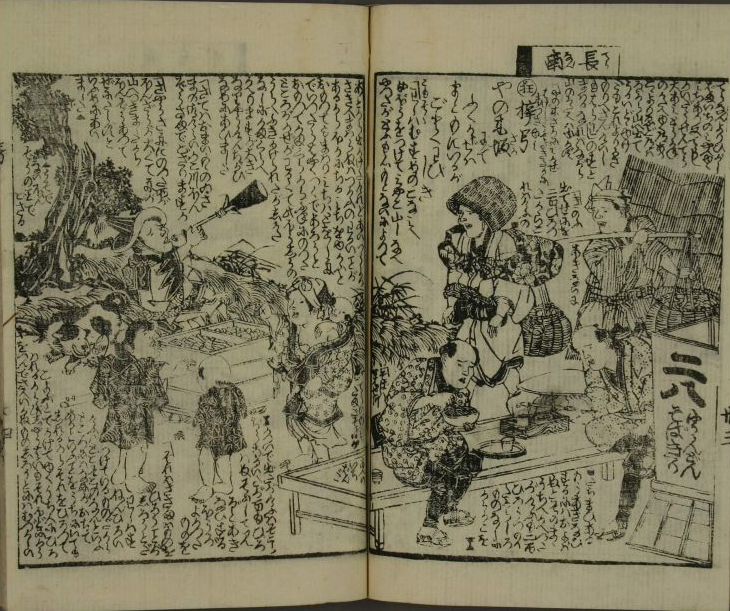

江戸時代は競争が非常に厳しくなりました。物売りたちは、奇抜な衣装を身に着けたり、趣向を凝らし注意を引き付ける売り声を使ったり、商売を魅力的にするための滑稽なしぐささえしました。

During the Edo Period (1603-1868) selling became desperately competitive,

and vendors began to don exotic costumes, use amusing and attention-getting

calls, and even perform engaging antics in order to attract business.

江戸時代は幕府の許可を受けて鑑札を持つ必要がありました。

例えば唐人飴売りは、中国服を着て、中国の帽子をかぶり、子供たちに飴を売る物売りです。

The tojiname uri, for instance, who sold candies to children, wore Chinese

clothes and a chinese hat.

彼は、飴を売る時はいつも、チャルメラを吹き、太鼓を鳴らし、彼の若い観衆を踊りながら喜ばせました。

He played a flute and drum, and delighted his young audience with dancing

whenever he made a sale.

十返舎一九 出典:ウィキペディア

十返舎一九 出典:ウィキペディア

唐人飴売りは、明治の中頃まで活動を続け、新年に見かけることができる七福神の印刷物を売っていました。

The tojiname uri, active until the mid-Meiji Era, sold prints of the Seven Lucky Gods (shichifukujin) that you see here and there every New Year.

人々がその印刷物を枕のしたに入れて寝ることで、その1年の幸運な夢を見させてくれます。

People slept with these prints under their pillows to induce a lucky dream

for the year.

そば売りは、背中に背負った棚に風鈴をぶら下げて、狭い街路に沿って鳴らしました。

Soba vendors hung furin (chimes) on the carries worn on their backs and

jangled their way along the narrow streets.

オートバイや拡声器が無くても賑やかな都市だったことでしょう。

It must have been a noisy city even without the help of motocycles and

loudspeakers.

江戸時代、焼きいもは人気でしたが、それらは、たぶん火災防止の法により、お店だけで売られていました。

Although yakiimo (baked sweet potatoes) were popular in the Edo Period,

they were sold only in sores - probably due to fire laws.

ただ煮たり蒸したりした芋が物売りによって売られていました。

Only boiled and steamed potatoes were sold by the stree vendors.

今日の下町では、リヤカーの底に乗せた気を燃やす窯で熱くした小石で間接加熱によって芋が焼かれています。

Today, in shitamachi, yakiimo are baked in pebbles that are heated by

a wood-burning stove in the bottom of a wooden cart.

一旦約1時間で十分に調理された芋は小石の中から書き出され、隣接した温かい場所に置かれます。

Once fully cooked (after about one hour), they are raked out of the pebbles and placed in the adjacent warming compartment until they are sold.

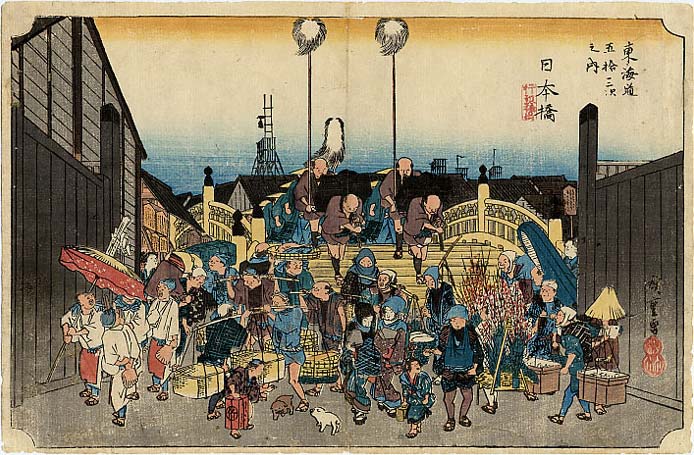

江戸時代は棒手売(ぼてうり)ともと呼ばれていて、天秤棒の両側に商品が入った樽やザル、桶、盥などを吊るして、日用品や食材、季節の商品などを売っていました。

東海道五十三次 国立国会図書館 所蔵

東海道五十三次 国立国会図書館 所蔵

豆腐売りは、ラッパを使って「とーふー」と聞こえるように吹きながら移動します。

江戸時代後期には町人の間に金魚を飼育して鑑賞する習慣が広まりました。池や盥に入れて上から鑑賞するだけでなく、ガラス製の球形の水槽を軒下に吊るしてしてからも鑑賞しました。

埋立地が大部分を占める江戸の下町では、飲料水の販売されていました。

隅田川から取ってきた水を飲んだ抵抗力の弱い老人が腹を下すことから、「年寄りの冷や水」ということわざができたそうです。

7世紀の日本では役人が旅をする必要があり、朝廷は食事と宿泊に対するおカネを要求する「駅のシステム」をつくりました。街道筋には「駅舎」の組織ができ、駅馬の用意がありました。

Traveling was a necessity for officials of seventh-century Japan, and

the government instituted a "station system" that required the

wealthy to feed and put them up.

それ以外の旅人はお寺や屋外で寝るしかありませんでした。

Other travelers, however, had to sleep in temples or outdoors.

平安時代には街道が整備されて「畿内」、「東海道」、「東山道」、「北陸道」、「山陰道」、「山陽道」、「西海道」、「南海道」の8つの街道に宿駅がありました。

国司や郡司をはじめとする地方官や防人の旅に加え、巡礼などで街道筋は賑わいました。

十世紀を待たず、旅館が利用されるようになりました。

It wasn't until around the tenth century that ryokan, or inns, came into

use.

巡礼や商品を売り歩く商人、仕事を探す人々のため、旅館は時代の経過と共に増加しました。

Their number increased over the following centuries due to religious pilgrimages,

merchants peddling their wares, and others looking for work.

1186年源頼朝による鎌倉時代に入ると「宿」の歴史は急速に進展しました。

源頼朝は「宿奉行」を設け全国の「宿」の統制と管理にあたらせ、従来からあつた「宿駅」を整備しました。

街道筋の一般家屋も一般の旅人を泊める「宿」の性格を持つようになりました。

江戸時代に入ると、徳川幕府の権力維持と地方諸大名の権力伸長を防ぐためにとられた参勤交代によって、街道の整備がさらに進みました。

江戸時代には京都から江戸までつながる東海道のような主要な街道にはたくさんの旅館が配置されました。

By the Edo Period (1603-1868) numerous inns were located along main roads

like the Tokaido, which extended from Kyoto to Edo (old Tokyo).

その当時の旅は、埃まみれで、時に危険で厳しい体験でした。

Traveling in those days was a dusty often dangerous ordeal.

参勤交代は、諸大名が一年おきに江戸へ出仕することを義務かした江戸幕府の法令で、そのため、一年おきに江戸と国許を行き来しなければなりませんでした。

諸大名が江戸を離れる場合でも正室と世継ぎは忠誠心の補償(人質)として江戸に常住しなければなりません。

The wife and children of powerfur lords were forced to spend in Edo by

the Tokugawa gavernment as an assurance of loyalty.

徳川幕府は、宿屋に対して厳しい規定を設け、宿場をチェックしました。また、異なる部類の人々が止まる様々なタイプの旅館を開発しました。

This government set up rigid regulations for inns and check stations,

and various types of ryokan developed to accommodate different classes

of people.

最も快適な旅館は、公家と大名のための本陣です。

The most comfortable inns were the honjin, for court nobility and local

lords.

武士の住居と旅館を組み合わせ、敵から客を守る十分な強さがあり、場合によって逃げることもできます。

A combination of samurai residence and inn, these were constructed to both

be strong enough to protect guests from their enemies and provide a choice

of emergency exits.

旅籠屋は一般の旅行者のための旅館です。

Hatagoya were inns for ordinary travelers.

旅籠屋の雇人は通りから宿泊客を引っ張ってきました。

Thier employees pulled in customers from off the street.

一旦捕まると、若い女性従業員が足を洗うための温かいお湯が入ったたらいを用意します。

Once caught, the guest was presented with a basin of hot water by a young waitress, with which to wash his feet.

その後、客はお茶お飲み、お風呂に入り、宿の部屋で夕食をとります。

After this he receive tea, took a bath, and had dinner in his room.

いくつかの点で宿の主人は宿泊客が怪しいか、そうではないか、確かめます。

At some point the owner would appear to ascertain whether the guest was

"suspicious" or not.

もし、怪しい場合は役人に報告します。

If so, this was reported to the authorities.

売春はそれらの宿の楽しみで、順調でした。

Prostitution was an attaraction at many of these inns, as it had been

right along.

19世紀半ばになり、競争が厳しくなりました。それは、東海道の53の宿場のうち34が客に売春を提供していたのです。

By the mid-nineteenth century, competition was tough: thirty four of the

fifty-three stations along the Tokaido had inns that provided prostitutes

for their customers.

比較的安い宿は、商人が泊ることができる商人宿です。

Cheaper inns called shonin yado were available for merchants.

最も低い部類の人には、宿泊と自分で食事をつくるための木を有料で買うことができる木賃宿です。

For the lowest class, there was the kichin yado which offerd only bedding

plus wood, for an extra fee, with which to cook one's own meals.

たくさんの一般的な旅館が第二次世界大戦後も営業していましたが、戦後の高度成長と共に劇的に数が少なくなりました。

Many general ryokan were still on operation after the Second World War,

but the numbers have shrunk drastically with the postwar prosperity.

澤の屋旅館

澤の屋旅館

旅館では宿泊客に浴衣が用意されているのが一般的です。

It's common for ryokan to provide yukaa for the guests.

旅館は通常1泊2食付きの料金です。

The ryokan charge usually includes two meals.

江戸時代に遠くにある神社へ参拝する巡礼の旅がブームになりました。

伊勢神宮への「伊勢参り」は庶民の憧れでした。

弥次さんと喜多さんが伊勢参りで珍道中を繰り広げる話が『東海道膝栗毛』です。