| Islamic Architecture in

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

|

Jiang su sheng 江苏省

MOSQUE (XIANHE SI) **

This is one of the time-honored ‘Four Great Mosques along the South China Sea’ together with those of Quanzhou, Guangzhou, and Hangzhou. Like the others, it also has a popular alias prefixed with an animal’s name, Xianhe Si (Crane Temple). Xianhe means a crane with eternal youth and immortality. The name is said to have been given to the temple due to the fact that the form of its layout resembled a soaring crane. Yangzhou, located slightly to the north of the Yangtze River (Changjiang), prospered as a hub of water transportation, when the Great Canal was constructed to connect the five great rivers in the ancient Sui era. In the Tang era, it became not only domestically but also an internationally important trade port routing to the South and East Seas. It was from here that the Buddhist high priest, Jianzhen (688-763), came to Japan, and furthermore Arabian and Persian merchants came here from the Middle East and made their communities.

There is a tradition that in the Southern Sung era, an envoy named Puhatin was dispatched by the Caliph in Bagdad to China and he propagated Islam in Yangzhou, erecting a new mosque in 1275 towards the end of that era. Although the precise year, recorded in the “History of Jianagdou Xian”, may be looked upon with suspicion, it is certainly the Crane Mosque. Although its precincts face front roads both on the south and north, the entrance is not on the side of the southern grand avenue but northern narrower street. Its premises are not so extensive and short in depth, so the laying out of buildings must have been difficult. One first enters through the Great Gate into a forecourt, on the right of which is the courtyard of the Great Hall (worship hall). Though there is a second gate and a front portico in the courtyard, they do not seem to be used frequently most likely because of their crampedness. Usually one goes straight through the Moon Gate into the small southern courtyard (the lecture hall’s court) from which one enters the worship hall directly. On the west of the southern court is a library, and on the south is the Hall of Sincerity (lecture hall). A small moon watching room protrudes from the Great Hall, bringing added interest and delight to the garden. Such a situation is rare, but the room is not towered, that is, this mosque lacks a minaret probably because this is not a Friday Mosque.

The Great Hall consists of a colonnaded front space before a hypostyle hall and then the Rear Mihrab Hall with the same five spans as the worship hall, separated by a wooden continual arched screen. Even if the two halls are used altogether at the congregational worship time, the insertion of a screen between the buildings is a characteristic of Chinese mosques. The Rear Mihrab Hall is much more extensive than usual and also used as a continuous part of the worship hall. The ceiling of its central part in front of the Mihrab is quite high, making its external appearance a square tower surmounted with a gambrel roof. The Mihrab, decorated with Arabic calligraphy, is lighted up from the tower, the ceiling structure of which is exposed like ornamentation. >

However, it might be possible that this hall would not have been the Rear Mihrab Hall, and the original one would have protruded to the west in a smaller scale and was removed when the western avenue was widened. If so, this explains the unusual proportion of the current Rear Mihrab Hall.

There are four time-honored tombs in China long revered as the ‘Four Great Sacred Tombs’ of Muslims who came to China in quite early times and passed away in China. Two are in Quanzhou, one is in Guanzhou and the other is here in Yangzhou as the Tomb of Puhatin, who is considered to have first built the Crain Mosque. This and the one in Quanzhou are designated as national key heritage conservation units, though not for their architectural value but as historical monuments that commemorate the introduction of Islam into China.

The legend that the prophet Muhammad sent his four disciples to the Tang dynasty to propagate Islam in China is a representative of it; a fallacy connected to the Four Great Sacred Tombs. The belief that Puhatin is a 16th generation of descendant of Muhammad is also the same; and that the sacred tomb of Woges in Guangzhou is a downright sham is described later. The garden has an area of 1.5 hectares, consisting of an old mosque area, an old tomb garden, and a classic Chinese garden. The tomb garden embraces Puhatin’s mausoleum and as many as 67 tombs of other Arabs. Every tomb forms a simple square brick house with whitewashed walls. In spite of tiled roofs, they are not wooden structures but brick ones. It is interesting to see that they are domed over corbelled pendentives, with arched entrances.

At the lowest part of the precincts (by the formal entrance of the garden) is an old wooden mosque on a small scale. It was erected in the middle of the Ming era. Being without any annexed buildings, it might have been a simple oratory. It is a single gable roof building of a moderate scale, with a colonnade in front facing a moderate sized forecourt. The interior is bright thanks to continuous rear windows. Its plan is Chinese style with a small Mihrab room protruding to the backyard. Jiang su sheng 江苏省

WESTERN MOSQUE *

Going south through the Great Canal from Yangzhou, one crosses the Changjiang River and soon arrives at a town with a population of about one million, Zhenjiang. The city has a long history since the Three Kingdoms period (220-280), getting its name of Zhenjiang in the Northern Sun era. The advantageous location at the intersection of the Changjiang and the Great Canal made it prosper as a commercial town.

Said to have been first constructed during the Tang era in legend, the Old Libai Si (mosque) of Zhenjiang was destroyed in the Ming era and again in the Cultural Revolution, but has now been rebuilt as a new ‘Arabic Style’ worship hall in the suburbs of the city.

One goes on a winding street, passing by an office, through a wooden gate and turning left, and the second gate with white walls on the right, at length, reaches a formal courtyard surrounded with some buildings. It is a mosque with an impression of having a great depth.

The worship hall is a single building with an area of 440 square meters, surmounted with a huge gable roof. Its width consists of five spans with two rows of columns. At the furthest points in the center is the Rear Mihrab Hall, separated by a three arched wooden screen with two columns. Jiang su sheng 江苏省

JINGJUE MOSQUE **

The capital city of Jiangsu Province, Nanjing, is counted one of the four great old cities of China, having had been the state capital through the age of the Republic of China. It was also the stage of the notorious ‘Massacre of Nanjing’ by the Japanese army in 1937; in addition it is the place of the tomb of Zheng He (c.1371- c.1434) who was a great Muslim to have made seven expeditions through the South Seas from Vietnam up to Arabia. However, in contrast to Yangzhou and Zhenjiang as trading cities, Nanjing was the central city of political and military affairs, not a place of commercial activities for Muslims, resulting in possession of no legendary old mosques. Even so, a famous mosque, Jingjue Si, which has been designated as a Jiangsu Province Key Heritage Conservation Unit, is said to have been first constructed in 1388 in the early Ming era by Zhu Yuan Zhang, the first Emperor of the Ming dynasty, Hong Wu Di (r. 1328-98). Although he was not a Muslim but a Confucian, he might have built the mosque to reward Hui soldiers who had contributed to establishing the Ming dynasty, disrupting the previous Yuan dynasty. At that time the number of Muslims in Nanjing exceeded 100,000.

At the beginning the mosque was referred to as the Three Mountain Street Libai Si. It seems to have covered an area of 67 hectares. Now, the mosque is located in a flourishing area in the center of Nanjing. Though it suffered a conflagration in 1430, happening to occur the day before Zheng He’s departure on his seventh and last expedition, he postponed it until the following year, and petitioned the Emperor Xuande to reconstruct the mosque at the expense of the treasury. The moment one steps through the Great Gate made of brick, one sees the remarkably tranquil precincts spread out in contrast with the busy outside streets. This is a courtyard type like the Siheyuan-form, on which one goes on to the left, the direction of Macca. However, since there is then an office building in the center of the courtyard, one has to go around it on one of either of the two paths in order to get to the inmost courtyard. Moreover, the office and the Great Hall are connected with a steel tectonic roof, which impairs the time-honored atmosphere of the courtyard.

On each side of the inmost courtyard is a lecture hall called Butterfly Hall, and in front is the Great Hall five spans in width. It is a hypostyle hall with a wooden screen of a kind of multilobed arches, one span before the Rear Mihrab Hall. The setting of the Minbar at the open arch, just one span right of the central arch, is much more convenient than in the Xianhe Mosque in Yangzhou. The Qibla wall in the Rear Mihrab Hall is painted with ornamental Arabic calligraphy in gold on a red background, which brings an exquisite brilliant effect to the worship space under light from windows on both sides. An hui sheng 安徽省

EASTERN GREAT MOSQUE *

Shouxian is a small city located near Zhunnan, to the northwest of Hefei, and it was referred to as Shouzhou until 1912. As it is a historical city surrounded with well-preserved ramparts from the Son era, it is designated one of the National Historical Great Cities of China, and also counted as one of the seven ancient great ramparts, together with Xian, Nanjing, Jingzhou, Xingcheng, Pingyao, and Suiwu.

The mosque is said to have been first erected in the Tianqi period (1621-27) near the end of the Ming era. Although it suffered much during the Cultural Revolution, it was restored in 1995-96 and recovered its well-balanced form in each building and grounds.

In contrast with many noted old mosques, which have small courtyards as a result of several enlargements of buildings, the Eastern Great Mosque’s courtyard is large enough to form a complete geometric spacious garden. A stone paved walkway of geometric pattern in the center of the garden extends to the ample Moon platform (terrace) in front of the Great Hall, accompanied with green zones on both sides, with trees planted regularly.

The imposing Great Hall (worship hall) has five spans in width with wooden latticework around the colonnade on the first floor and is covered with a Chongyan (twofold) gambrel roof. Between the two folds is a tablet, on which is written ‘Wu-xiang-bao-dian’ meaning a precious edifice with no idols. The lecture halls are five-spanned Danyan (single) gable roof buildings, which were used as a school for children. An hui sheng 安徽省

SOUTHERN GREAT MOSQUE **

Anquing is a water transport hub city, located in the middle of the Yangtze River (Changjiang) that connects Nanjing and Wuhan, a sturdy city with a population of about 600,000 people. Its Southern Great Mosque is said to have been first constructed in the fifth year of the Chenghua period (1469) during the Ming era. In spite of having been destroyed by wars at the end of that era, it was rebuilt under the rule of Emperor Kangxi during the Ming era.

The precincts of the Southern Great Mosque are not only irregular in shape but also with a large difference of altitude. The current main entrance faces the upper busy street, which seems to have been arranged in later years, making one approach through narrow alleys between banal concrete buildings, on which is a small wooden moon-watching tower.

The original main entrance to the compound is far beyond it (now at the rear) facing a calm tasteful street, from which one originally approached the worship hall. However, due to the scale of the Great Hall occupying as large as 600 square meters, the courtyard reached through the second gate is disproportionally narrow and out of balance with the Hall. This is not the result of the enlargement of the Hall, because the Hall is a single building surmounted with a simple large gambrel roof, the top of which is very high exceeding 20m. On both sides of the courtyard are small lecture halls and the Great Hall’s façade gives a stately impression with two-fold tiled eaves sustained with continual bracket sets. Its interior, available to accommodate 1,000 worshipers at the same time, is an extensive hypostyle hall with a spectacular view of the exposed roof structure. It is painted in a single color, while the Rear Mihrab Hall makes a splendid sight with columns of golden calligraphy, an orange colored tablet, and the brilliant Mihrab.

Despite its confined setting in the compound, this mosque is overall appreciated as a work of high quality design.

Municipality of Shang hai 直轄市

SONGJIANG MOSQUE ***

Islam arrived in the Shanghai region in the 13th century during the Yuan era, and now about 50,000 Muslims reside there, but no old mosques have survived within the city of Shanghai. Although the Western Mosque has been reconstructed with reinforced concrete and renamed the Xiaotaoyuan Mosque, it, along with most new mosques in China, does not have much architectural importance. The most worthwhile mosque to see in Shanghai is in the Songjiang district in the suburbs. While it is now a suburban district of Shanghai, Songjang district was once the main city itself by the name of Huatingxian. It prospered with cotton industry until the 14th century, and one part of it, Shanghai, became independent in the 13th century and formed the current urban area in the 18th century. Huatingxian altered its name into Songjang, gradually becoming a commuter town of Shanghai, and recently being redeveloped into a tourist spot.

Although the Muslim community of Songjiang numbers only close to three hundred nowadays, the Songjiang Mosque is the oldest in the Shanghai area, once called Zengjiao Si (literally meaning True Teaching Mosque), as is known from a tablet made in 1407.

Its precincts are quite extensive with a verdurous woody garden on the east side. From the entrance of this garden the east-west axis stretches straight up to the Rear Mihrab Hall of the mosque, but now the Great Gate has been built in front of the northern redeveloped commercial street and a new square. Outside of this gate has been erected a Zhaobi (Mirror Wall) to block the view through to the inside, and furthermore beyond the gate is an inner brick Zhaobi, on which the name of ‘Qingzhen Si’ is written downwards in Chinese characters. Turning 90 degrees here, one is on the mosque’s intrinsic main axis facing west. By going through an arched opening in the wall, one enters an extensive woody garden, while passing through the second gate opposite, one is led to the courtyard in front of the Great Hall. Like this, the large premises are divided into human-scaled sections, leading visitors up to the inmost worship hall, and giving familiar impressions akin to that in residences. This is the special feature of this mosque’s planning.

Furthermore, the second gate has a unique design, functioning also as a Bangke Tower (Minaret). Its lower brick part is from the Yuan era. The ceiling of the inside space between two arched openings is a dome on pendentives composed with corbelled brick tiers.

On both sides of the courtyard are lecture halls as usual (now used as exhibition rooms), and in front is the front hall of the Great Hall. If taking a diagonal side lane from the courtyard, one can go around the Great Hall through an old oak tree garden and a quiet tomb garden. Beyond the front hall is the square worship hall with four columns and a Minbar from the Ming era. What is curious is the existence of a buffer space between the worship hall and the Rear Mihrab Hall, like in the subsequent Zengjiao Mosque of Hangzhou, giving the Mihrab a remoter impression. Though this Mihrab looks like an altar to do some ritual at, the Mihrab is originally and actually nothing but an indicator of the direction to Macca. Such a solemnly treated special Mihrab is never seen in the Middle East.

Since this Rear Mihrab Hall was built of brick in the Yuan era, it might have been intended explicitly to look separate from the wooden worship hall from the Ming era. The ceiling is a dome as that of the Bangke tower, at the height of eight meters. The Mihrab is magnificently decorated with Arabic calligraphy in gold. Zhe jiang sheng 浙江省

ZENGJIAO MOSQUE (FENGHUANG SI) **

This is one of the time-honored ‘Four Great Mosques along the South Sea’ together with those of Quanzhou, Guangzhou, and Yangzhou. Like the others, it also has a popular alias prefixed with an animal’s name, Fenghuang Si (Phoenix Temple). Fenghuang is an imaginary spiritual bird in China, with a peacock-like figure. It is said that the mosque’s early shape (plan?) may have resembled a fenghuang. It might also have been related to the nearby mountain called Mt. Fenghuang, in the south of the city. n the Yuan era a large number of Muslims of the preferentially treated ‘Semu (literally meaning ‘color-eye’) People’ immigrated to Hangzhou from Kaifeng and erected many mosques. Marco Polo, who visited here about 1280, admired the prosperity of the city, writing that its population amounted to one million, which implies that Hangzhou was the largest city in the world. The great 14th century Muslim traveler, Ibn Battuta, wrote in his travelogue about the Friday Mosque and other mosques in the Muslim quarter in Hangzhou, and Mr. Tasaka conjectured that this Friday Mosque would have been the Fenghuang Mosque. The current Zengjiao Mosque is in the center of the city, facing Zhongshan Road, with a not so vast land of 2,600 square meters. When the front road was enlarged in 1929, the land area was reduced and its brick Great Gate surmounted with a five-storied minaret was destroyed. Although there is a legend that the mosque was built in the Tang era, there is no evidence of this. It seems to be more reliable that the mosque was first constructed in 1281 during the Yuan era and was rebuilt from 1314 to 1320 due to a conflagration in the age of Yanyu. There remains an Arabic inscription on a tombstone of a Persian missionary by the name of Ala al-Din that he had contributed money for the reconstruction. After that the mosque seems to have been reconstructed again in 1451 or 1646 during the Ming era.

Plan of Zengjiao Mosque, Hangzhou Among the current buildings only the Rear Mihrab Hall made of brick is from the Yuan era and its wings on both sides were added in the Ming era. The worship hall was reconstructed in 1953 with reinforced concrete with the reason given that the former wooden structure had deteriorated. Its interior has been made like a small gymnasium, the impression of which is extremely different from that of the Rear Mihrab Hall. And the two are completely cut off from each other and have a buffer space in between as in the Songjiang Mosque in Shanghai, forming a singular plan with a wasp waist. It can be said that this is a unique mosque without parallel. In the case of the Songjian Mosque, there is not excessive strangeness, since its Rear Mihrab Hall is on a small scale. However, that of the Zengjiao Mosque is as large as 8.3 meters in diameter for the central dome, 6.7 meters for that of the dome on the right and 7.3 meters for the left, making, unusually, the total width of the Rear Mihrab Hall larger than that of the worship hall itself. As one cannot see into the wings from the worship hall, I wonder how they use these spaces. Regular worship might be carried out within the Rear Mihrab Hall only.

The central dome is roofed with tile in a two tiered octagonal cone as if it were wooden structure and those of both sides are single tiered hexagonal with turned over eaves. Their structural system is a brick dome supported with corner pendentives made of corbelled bricks as usual. Since it has no columns and beams, the system is called a ‘beam-free brick edifice’. The wooden Mihrab is from the Northern Sung era, on which are engraved Arabic passages from the Koran. Fu jian sheng 福建省

NANMENDOU MOSQUE

The capital of Fujian Province, Fuzhou, a time-honored city since the Han era, is designated one of the National Historical Great Cities in China. In Nagasaki, Japan, the Sofuku-ji, a Buddhist temple in Chinese style, belonging to the Oubaku sect, was founded by the Chinese priest, Chaoran (Chounen in Japanese), who had come from Fuzhou in the late Ming era, so it is also called Fuzhou Temple. On the other hand, in Fuzhou there are no remarkable old mosques in spite of having flourished as a trade port city in and after the Sung era.

There remains a false legend that the Nanmendou Mosque was first built in the 2nd year of the Zhenguan period during the Tang era, or 628 under the rule of the second Tang emperor, Taizong, intending that Islam had been brought to China at such an early date. However, during the year 628 Muhammad was still living in Madina and fighting the Arab army of Makka, so the theory that a mosque was erected in China in that period is an unrealistic fallacy. Nanmendou is the name of the district where the mosque is located; one is led to the Chinese style quaint wooden mosque via a long passageway after passing a three storied concrete gate facing the front street. The current mosque is on a small scale, forming a Siheyuan-like composition, with the Great Hall in front and lecture halls on both sides. The Great Hall’s facade does not give a dignified impression due to its low eaves, though its interior is an unexpectedly extensive hypostyle hall, with three spans in width and four in depth. Since it is fairly deteriorated, it needs to be wholly repaired at some stage.

What is most impressive is the space just before the Mihrab, with the floor raised two steps higher as if it were a stage. The space with columns on both sides and an upper beam, surrounded with balustrades, can be described as a Rear Mihrab Hall protruding forward, in contrast to general cases. In any case, it is a custom only seen in China to make the Mihrab hall a special space that looks as if some divine rituals could be performed there. Fu jian sheng 福建省

SHENGYOU MOSQUE (QILIN SI) **

This is one of the historic ‘Four Great Mosques along the South Sea’ together with those of Guangzhou, Hangzhou, and Yangzhou. Like the others, it also has a popular alias prefixed with an animal’s name, Qilin Si (GiraffeTemple). Its original Arabic name was ‘Masjid al-Ashab’ (Friends Mosque), which was translated into ‘Shengyou Si’ (Sacred friends Temple), but it has been wrongly called ‘Qing Jing Si’ (Pure and Clean Temple), which is used as the more formal name nowadays. Although current Quanzhou is a calm city of commerce and industry on a small scale, in the Sun and Yuan eras it was highly developed as the most flourishing international trade center in China. As it was the starting point of the so-called Silk Route on Sea, many Arab and Persian merchants came here, forming Muslim community districts. Marco Polo described this city by the name of ‘Zaytoun’ in his “Travels”. Zaytoun means olive in Arabic; the city’s name is said to have derived from a legend that Liucongxiao planted olive trees here in the 10th century. Ibn Battuta, the Arab traveler from Morocco, wrote in the travelogue of his 24 year journey from Macca to China through India that he landed Zaytoun in 1345, found it a magnificent city, was welcomed by Muslims on the spot, could not find zaytouns in the city of Zaytoun, etc. It was also from the port of this city that Zheng He would start his many great expeditions through the South Seas (1405~33). Once there were nine mosques in Quanzhou, but now only the Shengyou Mosque has survived.

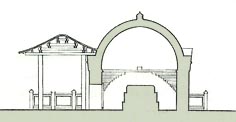

Plan of Shengyou Mosque, Quanzhou Although it is undoubted that the Shengyou Mosque, facing Tumen Jie Street in the center of Quanzhou, is the oldest among the extant mosques in China, its current remains are from a reconstruction in 1310 during the Yuan era, said to have been contributed to by a Persian named Ibn Muhammad al Quds Shirazi. It seems to have faithfully followed the original form. The Great Gate was also constructed at the same time, but the Bangke Tower (Minaret) built over it collapsed in the Quanzhou Earthquake in the Mingli period.

This mosque is unique in various ways in China, having much intimacy with Middle Eastern mosques rather than being a Chinese style mosque. This fact indicates the antiquity of this structure, that is, it is not Hui people but Arabs and Persians residing in Quanzhou in early times that brought the architectural style of their homelands and constructed it here for their own daily worship. On top of that, there are many unusual points in the layout of buildings: there is no main axis from the Great Gate to the Mihrab, and no courtyard in front of the worship hall, while the mosque’s wall, tightly closed to the front street, has many windows. Were those windows intended to be seen through in order to interest Chinese passers-by in Islam? Only in Egypt is such a feature in mosques not rare. Because it was difficult to get extensive land for a building in the heavily built-up city of Cairo, mosques had to open windows not only to their courtyard but also to the front street.

The Great Gate of the Shengyou Mosque is a Persian-type ‘Pishtaq’ with an Iwan, the arch of which is ten meters high and its inner half dome has ribs, while the rear half dome is carved in the Muqarnas pattern. The height of the gate is twelve meters and its roof was used as a moon watching terrace. Its circumferential parapets have crenelated moldings as in the Middle East. The worship hall called Fengtian Alter, an Arabic-type hypostyle hall of 600 square meters that originally had 12 stone pillars. Since there are no traces that those pillars were connected to walls by arches or vaults as in the Great Gate, the roof is supposed to have been a wooden flat structure, which was popular in Arabic type mosques, but is now open to the sky. What is most characteristic is the central Mihrab area protruding to the rear, which might suggest that this was the origin of the Rear Mihrab Halls of later Chinese style mosques. In the Middle East such style of mosques do not come to mind either in Arabic or Persian styles, although far off in the Maghreb one finds small room-like Mihrabs. As for the ogee arches, though a large one is used for the Iwan of the Great Gate, due to its innate instability they are mostly used, in the worship hall, as blind arches in the walls, without the worry that they may collapse. However, every window along the street does not have an arch on the top but a horizontal lintel. These facts may indicate that despite the demands by Arabs or Persians for arches, Chinese masons were not used to arch structures, so they depended on placing arches in walls and lintels.

While most stone is granite, only the Great Gate was built of green color stone, a kind of basalt, which is not found in other parts of China, and its skillful piling of stones is much admired. This prominent gate with the ogee arch was possibly constructed by the hands of masons who came from the Middle East.

At the foot of Mt Qingyuan in the suburbs of Quanzhou there is a pair of old anonymous tombs locally called the Lingshan (Spiritual Mountain) Holy Muslim Tomb. It is designated as a National Key Heritage Conservation Unit, though not for its architectural value but for its historical value as a time-honored tomb as old as the advent of Islam to China.

This legend of the Four Sages had been disseminated since before that document, and Chinese Muslims were proud of it, making pilgrimage to these old tombs. However, this legend is an utter fallacy; the Wude period was at almost the same time that Muhammad moved was moving from Makka to Madina (the Hegira), having a hard time to establish Islam, making it impossible to dispatch his disciples to propagate in far off China.

According to one document, these two granite tombs were repaired in 1323 during the Yuan era. Their roof was built much later, in 1962, making this site an open mausoleum. In the rear cloister are seven inscribed stone panels, one among which is about the worship ceremonies carried out by Zheng He on the occasion of his fifth overseas expedition in the 15th year of the age of Emperor Yongle during the Ming era (1417). Guang dong sheng 广东省

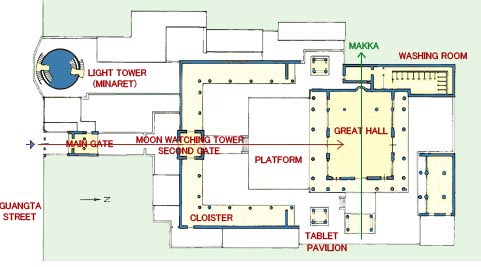

HUAISHENG MOSQUE (SHIZI SI) **

This is also one of the historic ‘Four Great Mosques along the South Sea’, together with those of Quanzhou, Hangzhou, and Yangzhou. Like the others, it also has a popular alias prefixed with an animal’s name: Shizi Si (LionTemple). Its formal name, Huaisheng Si, means the mosque for yearning for the prophet Muhammad. Despite its historical origin, the Great Hall is a building reconstructed in modern times, in 1935, and it is only the minaret that can be proud of hundreds of years of age. As the word minaret is derived from the Arabic Manar (Manara) that literally means a place of light, minaret was translated into Chinese as Guangta, or a tower of light. Since the minaret of the Huaisheng Mosque became the symbol of the mosque, the whole mosque itself came to be popularly called the Guangta Si (Light Tower Temple) or Huaisheng Guangta Tower Mosque, and its front street also came to be designated as Light Tower Street.

Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong Province, is a grand city with a population in excess of eight million people. It has been prospering since ancient times, and especially in the Tang era it was in the most important position for the South Sea trade. A large number of merchants came here from remote Arabia and Persia, as shown in the records of the Rebellion of Huangchao, which is said to have caused the downfall of the Tang Dynasty and through which numerous Persians and Arabs were killed in Guangzhou. Though there is a legend that the Huaisheng Mosque of Guangzhou was first built by a Muslim missionary named Abu Woges who came from Arabia in the 7th century (in the 630s), this is, needless to say, unbelievable as mentioned before in the chapters on Yangzhou, Quanzhou, and Fuzhou. There are also many books in which it is written that the mosque was first erected in the first year of the Zhenguan period (627) under the rein of the emperor Taizong, but it is based on, as also mentioned before, many false epigraphs on stone for the purpose of lending authority to Chinese Islam, suggesting that the four disciples of Muhammad came to propagate Islam in China in the early period of the Tang era.

Okimichi Tasaka conjectured in his book “The Advent and Diffusion of Islam in China”, freely using abundant historical sources, that the Huaisheng Mosque was constructed in, or not much later than, the Kangxi period during the Northern Sun era by a contribution of a wealthy Muslim by the name of Abdullah. Given those facts, the current minaret is considered to have survived the fire of the Qing era because of its nonflammable material of brick; it turns out that it brings us to the architecture of the Yuan era. Although the other buildings were rebuilt many times, becoming Chinese style wooden edifices, they must have taken the Middle Eastern style of stone or brick mosques in their first construction and reconstruction stages in the Yuan era, like the Shengyou Mosque in Quanzhou. In the late Tang era, in or around 880, Ibn Wahhab, belonging to the Qurayshes, came to China as an envoy to be received by the emperor in Changan (now Xian), but did not leave any record of the mosques in Guangzhou or Changan. This mosque of Guangzhou might not yet have existed in the Tang era.

The minaret of the Huaisheng Mosque is of an extremely rare type hardly ever seen in China, rather having affinity with the round-type common in the Middle East. It is 36m high with two tiers, the lower of which embraces a double spiral stairway that leads to the roof terrace. The Azan, or call for prayer in the mosque, used to be announced from there five times a day. The minaret is tapered off to the top and its wall has no ornaments, only plastered in white on the piled bricks. It seems that skilled craftsmen of arabesque decoration had not come to China. It is said that a sculpture of a golden cock was once on the top, but has been lost in an earthquake or a fire, and the tower also functioned as a lighthouse with a lamp on the roof at night for Arabian ships sailing the near Zhujiang River. Since, as mentioned above, the English word minaret is probably a corrupted form of Arabian Manara, meaning light house as a place of light, the Chinese translation Guantgta, Tower of light, was a proper denomination. Japanese architect Chuta Ito surveyed this tower in the 43rd year of the Meiji era (1910) and later wrote an article entitled ‘A Hui building in Guangzhou’, describing that the wall was 1 foot and 7 inches, the central pillar 12 feet and 5inches in diameter, each step 4 feet and 5 inches in width, and each brick 7.5 inches by 3.2 inches in size.

Although the Huaisheng Mosque’s precincts are suitably extensive at about 3,000 square meters, the site is so much set back that visitors feel that it is a long walk along the approach lane from the first brick gate up to the second, actually it is not so long. The second gate is two storied, functioning also as a moon-watching tower with a grand two tiered tiled roof.

The new Great Hall with circumferential porticoes has a Chinese style external appearance, but its interior space is a large astylar hall with conspicuous reinforced concrete truss beams, betraying the natural expectation that its traditional design would continue from the outside.

In China there are four tombs deeply revered by Muslims, known as the ‘Four Great Sacred Tombs’. They are said to be for the four sages who came to China to propagate Islam from Arabia in the extremely early stage of the development of Islam and who passed away here; two are in Quanzhou, one in Yangzhou, and the other is here in Guangzhou: the tomb of Woges, who is said to have first erected the Huaisheng Mosque. His tomb, located in the Muslim Tomb Garden on the north of the mosque, is the most famous among the four, called the ‘Preceding Sage’s Tomb’ in particular. Woges, so called in China, was one of the disciples of Muhammad, Sa’d ibn-Abu Waqqas, said to have been Muhammad’s maternal uncle. A legend tells that he was sent to China by Muhammad in the period of Wude (618-626) under Gaozu, the first emperor of the Tang dynasty, arriving at Guangzhou via the Persian Gulf in the first year of the Zhenguan period, and then constructed the Huaisheng Mosque. However, the historical fact is, on the contrary, that Waqqas was a grandson of Muhammad’s maternal great-grandfather, converting to Islam at the age of seventeen, and becoming one of his faithful disciples, serving with distinction through the conquest wars of Syria or Persia, and after having served as the governor of Kufa he died at the age of 70 or so, buried in Madina. It is clear from this acount of his life, he never came to China.

It seems that a tomb of some missionary, who came from the west during the Tang or Sung era, was eventually during a long period connected with the name of Sa’d ibn-Abu Waqqas. The legend of Waqqas occurred in the middle of the Ming era and has been adorned with various stories. The tomb was covered with a domed roof at some stage, added an open wooden prayer hut in front, and the tomb garden came to occupy two hectares in extent, in which Muslim tombstones were erected in various ages, making the garden a verdurous and tranquil space.

The brick dome of the Woges Tomb is one of the oldest extant in China. In spite of an opinion insisting that it is from the Tang era, it was most probably constructed in the Yuan era because of its squinches made in the same method as in the Zengjiao Mosque in Hangzhou. However, it is completely different from another Yuan era small dome on the Rear Mihrab Hall of Dingzhou’s mosque in Hebei Province in terms of the style of squinch as well as roofing system. Special Administrative Region 直轄地

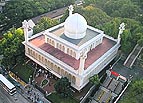

KOWLOON MOSQUE

Xiangang is the pronunciation in the Beijing dialect, though the Cantonese one is Hongkong, and also called and written as Hong Kong in English through colonial times. Historically it has always occupied a special position in China. I wonder if it is because of its development as a colony directly ruled from Britain that it does not have a Chinese style mosque. Among its mosques the largest is in the city of Kowloon on the opposite shore of Hong Kong Island. It seems to have originally been a worship place for Indian Muslims belonging to the British troops stationed here. Although it was first built in 1896, it collapsed in 1980 and reconstructed in 1984 on a high corner of Kowloon Park facing flourishing Nathan Road. As an urban type mosque it includes the entrance and a grand hall on the first floor, the main worship hall on the second, and the women’s worship hall on the third. The mosque is not necessarily a very high quality architectural piece, but it tried to incorporate traditional elements, such as arch and dome, in a modern style building, based on a square plan with moon watching towers (minarets) on the four corners of the second floor roof, and a central dome on the third floor roof, forming a quite symbolic composition if seen from the air.

The Great Hall for men on the second floor is a hypostyle hall made of concrete, and its central part has a two story high ceiling, which is capped with a symbolic dome adorned with mirror pieces. From the women’s worship hall on the third floor one can look down the second floor. Such a connection between men’s and women’s worship spaces is a new departure in mosque architecture. Yun nan sheng 云南省

ZHENG YI LU MOSQUE

Kunming is the large capital city of Yunnan Province, with a population of 4.8 million people. It is located at an altitude of close to 2,000m, enjoying a pleasant climate despite being in southern China. Since the rule of Yunnan Province by the colored-eye Muslim, Sayyid Ajall Shams al-Din Omar, during the Yuan era, there have been a large number of Muslims in this province, including Zheng He in the Ming era.

The former Zhengyilu Mosque, also called Southern Mosque, was said to have been first erected by Sayyid Ajall. In spite of its worthy history of 400 years as the oldest mosque in Yunnan Province, it was, I do not know why, demolished in 1997 and rebuilt of reinforced concrete on the same site. It is a typical case of demolition and reconstruction, and yet its current building is almost worthless from the architectural point of view; there seems to be scarcely any pursuit of new mosque architecture by the hand of architects in China.

In contrast to the western style mosques in the Xinjiang Uygur region, one of the features of the inland Chinese style mosques is the projection of a space around the Mihrab to the rear of the worship hall, by the name of Rear Mihrab Hall. However, the Yunnan Province does not adopt such a style and does not have an independent Mihrab space. The Mihrab is either embedded in the Qibla wall or treated as a small open space demarcated with two columns, as seen in the old and new Zhengyilu Mosques of Kunming. Yun nan sheng 云南省

SOUTHERN GATE MOSQUE *

Although Dali is a relatively small city with a population of 420,000, it has a long continuous history since before the Common Era, having been the capital of the state of Dali from the middle of the 10th century to the middle of the 13th, for more than 300 years. It declined after the status of capital was moved from Dali to Kunming, but it still keeps the cultivated appearance of an ancient city encircled with ramparts. It is located at an altitude of about 2,000m. In spite of one third of its population consisting of Bai people, the Bai People Autonomous Region, the capital of which is Dali, also embraces a large number of Hui people, as the result of a historical event when an Islamic power administrated this region from 1852, when Du Wenxiu, bearing the Islamic name of Sultan Suleyman, rebelled against the Qing dynasty, an administration that continued until 1872. As a result there remain two old wooden mosques, though on a small scale. The larger one is the Southern Gate Mosque. Facing the front street there is a three storied concrete hotel, accompanied with tile-finished concrete minarets on both sides, and the center of its first story functions as the entrance gate of the mosque set back a little distance. When going through the forecourt used as a parking lot nowadays, one goes up a flight of stairs to the raised ground, and through a wooden gate-cum-office building of two stories into a quiet courtyard, around which is a lecture hall on either side and the worship hall in front.

The Great Hall, of three spans in width, was constructed in the 14th century, and is said to have been heavily repaired in the Qing era. Its well-proportioned serene aspect with a front flight of steps, a pair of trees piercing them, and a grand tiled roof with slight curvature is quite impressive. It is only regrettable that the lecture hall on the left is discordantly made of concrete.

The Old Mosque of Dali stands along a narrow street called Renmin Lu in an old quarter. Through a wooden gate on the verge of rot one goes into an L-shaped long lane and finds a courtyard beyond the wooden second gate. The mosque layout is similar to that of the Southern Gate Mosque, but the right side of the courtyard is not closed with a lecture hall, which can be found at the furthermost spot in the right side open space. It has no minaret.

The Great Hall is predominantly three spans in width, but with an added half size span on both sides like at the Southern Gate Mosque, but giving an unconstrained impression, unlike the latter that is oppressed by closely located lecture halls on both sides. Its interior displays a much more antique atmosphere than the Southern Gate Mosque and the beams are colorfully painted like the outer bracket-sets under the eaves. The Mihrab space slightly protrudes on the rear, connected with two columns to the front by lower level beams, emphasizing the presence of a square space around the Mihrab. (10/05/2008) |

E-mail to: kamiya@t.email.ne.jp