|

MIMAR SINAN

The greatest architect in the history of Turkey is Sinan bin Abdülmennan. Architect is called ‘mimar’ in Turkish and Persian; there are no Turks who don’t know of ‘Mimar Sinan,’ because he is a Turkish national artist; artists are represented by architects in the Islamic society due to the prohibition of idol-worship, which didn’t allow sufficient development of the arts of painting and sculpture depicting figures of creatures (i.e. idols).

As it was in the 16th century that Sinan lived as an architect, he was a contemporary with Michelangelo in Italian Renaissance, close to fifteen years younger than him (let’s fix on 1491 provisionally the year of his birth, though there are various accounts of it). While Michelangelo was not only an architect but also a painter and a sculptor at the same time in the Christian society that admitted iconolatrous arts, Sinan as a Muslim devoted himself entirely to architecture.

However, Sinan’s patron was the Sultan Suleyman I (1494-1566) who built up the zenith of the Ottoman Empire during his long rule of forty-six years and treated him as the royal chief architect throughout his life; therefore Sinan’s field of activity was tremendous, under the protection of the empire’s political and financial power.

Since the Ottoman dynasty held both secular and religious power, there was no confrontation and struggle like what were often brought about in Europe between the Pope and Emperor.

While it took decades or occasionally more than 100 years to complete a cathedral in Europe, Sinan could accomplish any mosque, no matter how enormous they were, in 10 years, as long as he kept the Sultan’s trust. He could be much more prolific than Western architects.

Worship hall and Minaret of the Suleymaniye, Istanbul

It can be said that he was a quite slow ripening architect, for he started his carrier at the age of about 48, when he was designated as a royal chief architect. In the very beginning, he was commandeered in the ‘Devşirme’ at the age of about twenty-one in Aghirnas, the village where he was born, in Anatolia. Devsirme was the system that took talented people in the Ottoman Dynasty, picking up smart and handsome boys from Christian families in its domain to discipline them into slave government officials or slave soldiers under the Sultan’s direct control. (It seems to be a strange system that Muslim Sultan picked up personnel from Christian families though.)

In other words, Sinan was originally not Turkish and Muslim but an Armenian or Greek Christian slave. One may be surprised to hear that the great architect was a slave, but actually it was those Devsirme people who formed the ruling class in the government and army of the Ottoman Empire, becoming government officials or soldiers in accordance with their aptitude after the conversion to Islam and elitist education.

It was a system that despite being slaves, they could be promoted to a commander in the army or a governor-general of a state, if they possessed ample talent and ability.

Sinan became chief of the infantry corps and the engineer corps after obtaining a good result in the ‘Janissaries’ (the soldiers in the Sultan’s Imperial Guard), and finally the chief of the Sultan’s bodyguards. He presumably acquired the techniques of architecture by constructing bridges or temporary barracks at various places and converting Christian churches into mosques and so forth in his period with engineer corps.

Although the Sultan was Selim I when Sinan was commandeered in the Devsirme, it was the following Sultan, Suleyman the Magnificient, who found the talent in him and appointed him a Royal Architect in 1539. After that, Sinan built the golden age of Turkish architecture, hand in hand with the Sultan who wanted to embellish the Empire with architectural prosperity.

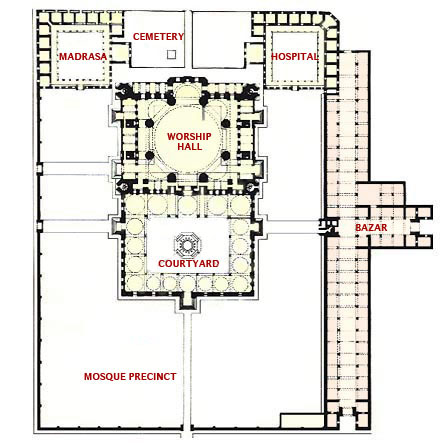

PLAN of THE SELIMIYE, Edirne)

(From A History of Ottoman Architecture, 1971, Thames and Hudson )

PLAN of THE SELIMIYE, Edirne)

(From A History of Ottoman Architecture, 1971, Thames and Hudson )

COURT ARCHITECT

His first large-scale mosque was the Şehzade Camii (Prince’s Mosque, 1543-48) in memory of Mehmed, a young dead prince of Suleyman. Showing his skill by the successful achievement of this mosque at the age of 57, Sinan was subsequently commissioned to erect Suleyman’s own great mosque, the Suleymanie, on the highest hill in Istanbul.

e accomplished this monument of great importance (1548-57) on the top of the capital with the ensemble of various-sized domes and high slender minarets, the silhouette of which fascinatingly decided the cityscape of Istanbul. He planned there a enormous complex of public facilities called ‘Kulliye,’ disposing Madrasas (schools), a hospital, a soup kitchen, a Hammam (public bath), a hospice, and so forth in a unified style around the great mosque.

Hagia Sophia in Istanbul

Istanbul, the old name of which was Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire before the Muslim conquest, held the supreme work of Byzantine architecture, the great Christian church of Hagia Sophia (532-537).

Despite having been constructed in very old times, 9 centuries anterior to the conversion of Istanbul to the capital of the Ottoman Empire, it overwhelmed Ottoman architects with its spectacular interior space under the majestic dome.

It can be said that the confrontation with this Hagia Sophia was the main theme of Sinan’s creative activity throughout his life.

At the Sehzade Mosque, Sinan designed an extensive space with a stable structure adding semidomes on the four sides of the main dome in a quatrefoil shape plan, while at the Suleymaniye he returned to the method of the Hagia Sophia, building two half-domes in front and behind of the great dome and making both walls on the right and left perpendicular with plenty of windows.

Although its scale was inferior to the Hagia Sophia, he established a logical formation that expressed clearly the flow of structural stresses, pointing up each structural component like arches or domes.

When Suleyman I, the greatest patron of Sinan, died seven years after the completion of the Suleymaniye, Sinan built his mausoleum along with that of his wife, the previously deceased Haseki Hurrem, in the rear garden (graveyard) of the mosque. Even though they are not as huge as Mughal emperor’s mausoleums in India, they are good examples of small domed tombs that harmonize resonantly with the great dome of the mosque.

Suleiman's Mausoleum and Cloisters of the Selimiye

An architect cannot design and supervise a monumental work by himself without collaborators due to its scale. Sinan could accomplish more than 300 works of architecture in his lifetime, thanks to the aid of reliable staff that made plenty of drawings and went to the construction sites frequently under his directions. (The organization of his staff and design affairs in the Royal Court was quite similar to the form of present-day architectural design firms.)

One more reason for his architectural fertility was that he continued to work on design until the latter half of his nineties, which was exceptional longevity at that time. That fact reminds us of the life of the 20th century architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who started to create large-scale buildings after the age of 50 and didn’t stop his design activity until ninety.

However, Sinan’s works don’t show as wide a variety of architectural expressions as those of Wright. The Suleymaniye, the Sehzade Camii, and his other mosques, all of which are akin to each other in their external appearances to a greater or lesser degree. He never made fanciful shapes that would surprise the society in every new work as Wright did.

In this respect, Sinan’s creative activity resembles Johann Sebastian Bach in the field of music, who was also quite fertile. The Bach's music doesn’t have so much gaudiness; every piece he composed is more or less similar to one another and makes a subdued impression. If what Bach pursued was rather inward logic than outward splendidness, it can be also said for the works of Sinan.

In this sense, Sinan’s work that corresponds to Bach’s supreme work the “Art of Fugue” should be the great mosque in Edirne, the “Selimiye.”

THE SELIMIYE (MOSQUE of SELIM II)

Exterior view of the Selimiye, Edirne

Exterior view of the Selimiye, Edirne

Selim II, who succeeded Suleyman I as the Sultan, commissioned Sinan to erect a great mosque, which should rival the Suleymaniye, on the highest hill in the city of Edirne (called Adrianople in former times) that had close relations to the new Sultan. The construction works on this mosque, into which Sinan at the age of eighty put all his energy, took from 1569 to 75. Since Selim II died two years before the completion, Sinan again designed the Sultan’s tomb in the precinct of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. He served through the reigns of four Sultans in the Ottoman Dynasty without a downfall; Selim I, Suleyman I, Selim II, and Murad III.

The Ottoman architecture was making its way toward an accurately different direction from Seljukid architecture following the Armenian fashion. Its most conspicuous feature was the huge development of the dome structure.

There was no other architecture that had such a good command of it to the extent of Ottoman’s. It was at the opposite end of the Arabic type hypostyle hall, covering so easily an astylar great space by a dome of thin membrane, as if it were a fabric tent in spite of it being a stone structure actually.

As the early mosques had small-scale domes, the turning point of evolution was the conquest of the Byzantine Empire and acquisition of its great church of Hagia Sophia, converting it into a mosque. Ottoman architects, Sinan in particular, set a major goal on overtaking and surpassing this great Byzantine dome structure. It was at the Selimiye in Edirne that Sinan thought to himself he had achieved it at length.

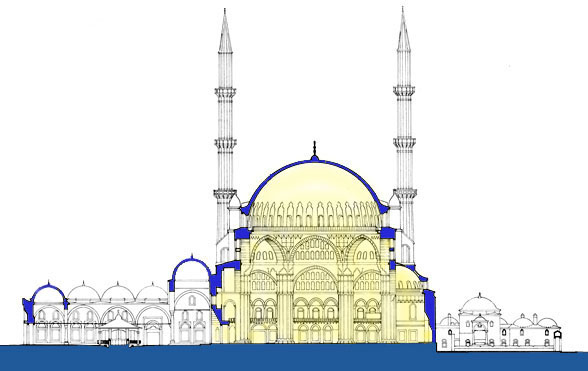

Cross Section of the Selimiye, Edirne

Cross Section of the Selimiye, Edirne

(From Henri Stierlin, "Architecture de l'Islam," 1979)

Sinan, who kept on imperishable desire for creation, adopted an octagonal plan in the Selimiye, after having tried various ways when building great domes in preceding mosques. While the four pillars supporting the great dome in the Suleymaniye came to show a little too strong a presence, here in the Selimiye eight continuous arches on the eight pillars could airily support the great dome of 32m in diameter, which surpassed eventually the Hagia Sophia.

Apart from the technological attainment in scale, it is more important that Sinan created a genuine Islamic space in the Selimiye, disuniting from that of Byzantine churches.

The domical ceiling of the Selimiye, Edirne

In the Hagia Sophia, Virgin and Child were depicted on the apse wall and Jesus on the dome ceiling; their narrativity gave the interior a mysterious atmosphere, and the contrast between the gloomy space and streaks of lights emphasized it still further. In the Selymiye as opposed to it, the lights from numerous windows on the walls and drum under the dome illuminate everything all over, leaving no dark or hidden places; one feels as if wrapped by the universe itself.

There might not be any other mosque that expresses so brilliantly the idea of Islam, that God sees through everything, and everybody is equal in the eyes of God.

The form of the interior, in which the eight uniform arches on the eight octagonally arranged pillars sustain the great dome, materialized a much more homogeneous and harmonious space of the universe than the previous Suleymaniye.

As Bach constructed the cosmic world of sounds in the “Art of Fugue,” Sinan materialized the cosmic space for worship with homogeneity suitable for the ‘Omnipresence of God’ ideology of Islam, creating the supreme work of Ottoman architecture at the Selimiye in Edirne.

On the external aspect, he simultaneously gave the city a genuinely symbolic appearance, encircling the great dome with four tall minarets, which stand as if spurting out towards the heavens. One can see it from many miles away on the top of the city.

Interior of the Selimiye and Statue of Sinan, Edirne

SINAN'S TOMB

Meanwhile, Ottoman architecture came to add courtyards in mosque precincts as before. But it would be rather fitting to call them ‘front gardens,’ since they are not continuous with worship halls spatially as Arabic type mosques. And the Selimiye also forms a mosque complex including a Madrasa and a hospital in a grand precinct, that is Kulliye, a public welfare facility based on ‘Waqf’ (charitable endowment) by the Sultan and the feudal lords.

Later at its west side, a Bazaar (market and business district) was added as a source of income for the maintenance of the facility. A royal architect Davud Aga, a disciple of Sinan, designed it.

Sinan's Tomb and Sabil, Istanbul

Sinan's Tomb and Sabil, Istanbul

Sinan, having designed more than forty Friday mosques that formed the cityscape of the capital, could have his residence in the precinct of the Suleymaniye Kulliye in Istanbul. He was a family-minded man like Bach, surrounded by his wife, a son, two daughters, and many grandchildren at home.

Seeing that prior to his death in 1588, he could build his own tomb with a Sabil (public water supply house) next to his house on the corner of this sacred site, one can know how deeply esteemed an architect he was from the Ottoman Empire.

(25/12/2007)

|